Issue 29 | Fall 2023

The Game Warden

Michael Loyd Gray

He’d come nosing around on Saturday afternoons, this tall, red-headed warden, because he’d taken a shine to my mother and pretended to recruit me for the conservation service. Even then, I suspected that was a front, but my mother and I were dazzled by his grin and jutting chin, a man full of the outward confidence a smart green uniform and holstered pistol on his hip bestowed. We always looked forward to him sauntering through the doorway, a slight limp in one leg that maybe most folks didn’t notice right off, but that was always the first thing that hit me as he shuffled into the room.

The game warden’s name was Grant Molloy, from over by Neoga, which meant he was out of his assigned territory on Saturday visits. But Grant liked to affectionately pat the butt of the pistol in its holster and say everywhere was his territory, and then he’d flash that Kirk Douglas grin, and whatever the question was became irrelevant. He had a habit of shifting his weight to his good leg and placing a palm over the pistol as if that somehow steadied him.

Grant got the limp in Korea when he was only seventeen but had his mother’s permission to join the Marines. He always wore a green baseball cap and took his time between questions, which I took for contemplation at first, but really it was just delay because he wasn’t comfortable talking about Korea. He often took off the cap and swept a hand through his raven-black hair and stared at the floor a moment before looking up sharply with a laconic answer. Sometimes, he’d merely shrug with a nervous smile.

This was back in early fall of 1967, just after the Summer of Love, which is ironic to me now, given the lack of it in Vietnam, a show my mother and I watched on the little Philco TV on a kitchen counter while we ate dinner. My father was in Texas, working oil rigs to make enough money to come back and maybe buy us a little house. He called from time to time, but not often enough to suit my mother, and their conversations were short, terse, and sometimes ended abruptly.

She endured his absence stoically and taught elementary school and did some house cleaning on the side for extra money. If I concentrate now, I can still hear the thumpthumpthump from the blades of those helicopters on TV as they dropped shouting American soldiers into dense green jungle and carried away silent dead ones in body bags. I was just fourteen.

One day, I sat in the living room with Grant, conservation service brochures spread out on the coffee table, like he was some door-to-door insurance salesman, or maybe a vacuum salesman, hawking his wares. My mother rustled about in the kitchen, Grant sneaking a look over a shoulder to catch sight of her. She was making him coffee and cutting Danish out of a foil container. I don’t think he much cared for Danish. He didn’t seem like a man who would order Danish in a cafe, but he loved getting Danish from my mother. He basked in her flittering about over him like a butterfly that can’t make up its mind where to light. The radio was on in the background and The Beatles were singing “Ticket to Ride.”

I swayed ever so slightly to the music and Grant noticed. He was a man of few words but noticed all the details. A hawk, I thought back then. Maybe even an eagle.

“You like them Beatles, do you, boy?” he said.

His voice was not unkind. Years later, it would occur to me that he must have known it was The Beatles on the radio without being told. Was Grant Molloy a secret Beatles fan? He sure looked more like the Hank Williams type.

I guess I was afraid to say I liked The Beatles, unsure how that would play with Grant. I told him my mother liked The Beatles, and that made him grin, and he glanced again over his shoulder at the kitchen. She closed the refrigerator door, and it made a loud bang, which made Grant wince, but he recovered his grin quickly. He shifted in his chair, stretching out the bad leg and rubbing it above the kneecap. The .38 in its holster on his hip rubbed against the arm of the chair as he got himself settled again.

“I suppose those Beatles are okay,” Grant said abruptly, but not grudgingly.

Just then my mother brought in the coffee and Danish and an RC Cola for me.

“What’s this about The Beatles?” she said as she sat Grant’s Danish in front of him on one of the conservation brochures.

He looked embarrassed and stuffed Danish in his mouth, probably so he could delay speaking.

“My, my, Louise, this is some fine Danish,” he finally muttered between swallows.

“Don’t be too impressed, Grant.” She touched his shoulder lightly. “That there is store-bought frozen. But I gave it a little jolt in the oven.”

Truth be told, it could have used a longer jolt and was still a bit hard. My mother was not a great cook. The oven was an inexact science for her. But Grant scarfed it down and nodded vigorously, dabbing crumbs from a corner of his mouth with a thumb. I think he would have praised her had she served him dirt on a plate with a cherry on top. Had the Danish been frozen solid, he would have attempted to eat it.

“Best Danish I’ve had in some time, Louise—frozen or not. Maybe the best ever, really. Not a damn thing wrong with frozen Danish.”

That was practically a speech, for Grant. A Shakespeare soliloquy.

My mother preened and pulled a curl of blond hair behind her pink ear. She smoothed her dress with both hands, looking at the floor. She missed having someone around to tell her she did something right. My father always complimented her on her roasts, even though she served them too bloody raw for his taste, with their moist, pink centers, and he had to smother the meat with 57 sauce or Worcestershire. Sometimes he poured some A1 sauce for good measure.

“Another slice of Danish, Grant?” my mother said hopefully. “More coffee?”

“Yes, to the coffee, and can I take a slice of Danish with me?”

“Why of course you can,” she said. “I’ll wrap it in foil.”

“How about one for Phil?” he said. Phil was a game warden, too, his partner. But he never brought Phil along on Saturday visits.

“I’ll just wrap the rest of the Danish, and you and Phil can fight it out over portions,” she called from the kitchen, her voice rising and chirpy like a bird’s, like maybe a cardinal.

“You’re a gem,” Grant called back, flashing the infectious grin.

“What kind of gem, Grant?” she called back.

He looked embarrassed, his eyes narrowing.

“A diamond, of course,” he finally managed to spit out, and he looked like someone who’d survived passing a gallstone. When he eased back on the sofa, the track lighting above caught his forehead just right, and I saw tiny beads of sweat. My mother banged the refrigerator door again hard, the noise digging wrinkles across Grant’s forehead.

“Mom’s not much of a cook,” I said after a moment of uneasy silence between us.

“Well, let’s keep that our little secret,” Grant said, leaning over the coffee table, elbows on his knees.

“It’s no secret,” I said, shrugging.

“But probably best kept that way, son.”

I confess I never liked him calling me son.

Or boy.

We always knew that Grant had a wife. And a son about my age. His wife’s name was Millie, the boy called Grant Jr. One day, Grant brought them with him to our house. He said they were visiting a relative nearby and he thought to say hello. He called my mother from a pay phone once they got to our town. I could hear her in the living room, telling Grant it was okay to swing by, and that she’d of course enjoy meeting his family.

I peeked around the corner as she put the phone down and she clasped her hands in her lap and gazed out the window, the sunlight streaming in, lighting up the blond curls at her ears. It was as if she’d been given some startling news and didn’t yet know what it meant or what to do about it.

Grant’s wife—Millie—said Grant had mentioned us a few times. We were those nice folks he’d helped when we had a flat tire one day outside the cafe at the Lake Raven marina. He’d retrieved the spare from the trunk and jacked the car up and changed the tire and made sure the lug nuts were good and tight and carefully put the bad tire in the trunk. He’d advised my mother that the spare tire didn’t look too good and that we shouldn’t rely on it, but ought to get a new one sooner rather than later. My mother touched his elbow when she thanked him. That was back when my father had already skedaddled to Texas, and she felt his absence keenly.

It was an awkward visit, Millie offering to help my mother clean up the dishes and my mother looking uncomfortable with another woman in her kitchen. She served everybody Danish, of course, but I turned up the oven a little bit more than usual and let it go longer, while she did some last-minute cleaning, so that the Danish was properly thawed and Grant and Millie both complimented it. Grant, of course, asked for a piece for Phil, and my mother wrapped it carefully in foil and found a small paper bag for it as well. We never ever met Phil.

When the Molloy family got in their car to leave for Neoga, Grant and my mother exchanged awkward glances at each other, neither knowing quite what to do and so they both looked away. I was by then a little older and more aware of such things. I looked away, too. I remember that Grant’s son, a pudgy, rather goofy-looking kid, waved goodbye to me, smiling like we were long lost brothers. I never saw that kid, or Millie, again.

Grant only visited one more time, and that day he stayed in his car in our driveway. My mother went out and they had a long conversation as she leaned in his window and then she touched his arm, and he backed out, and I watched his car until it went out of sight. If he ever came back, it was when I wasn’t home, and my mother never mentioned any visits by him. I never asked.

My father never came back from Texas.

I don’t think my mother was even surprised by that, as if she’d been waiting for the other shoe to drop for a long time, the wear and tear of anticipation—of dread—seeming to deepen rings under her eyes. Sometimes, as she got ready to go to school, she’d stare at herself in the bathroom mirror and then think to massage some facial cream under her eyes.

We would find out much later that my father had another family in Texas, a young son and daughter. My mother didn’t volunteer their names and I didn’t ask. My father sent money to us from time to time—guilt money, my mother called it. Bribery, when she felt especially low about it all. The payoff.

It took some time to do the divorce, to sign all the papers, my father paying for it all with oil-rig money and adding some extra. I remember he said in a brief note that he was making money hand over fist, that there could be work there for me, too, when I got a little older. It was hard work, the note said, but honest work. Salt-of-the-earth labor. He called me and tried to explain it, but he was not good at explaining things, and he called several other times, but we said very little. He invited me to Texas, to meet my brother and sister and his new wife, Thelma, but I never went, and he stopped calling.

Thelma, who sounded like she might be a nice lady, would send cards at Christmas and on my birthdays. And not just the plain ones you see in the racks at Walgreens. She’d buy colorful ones with nice artwork in them. She would include a pleasant note and a reminder to visit any time at all. I think she meant it, too. She always added a smiley face under her signature on the cards. Her signature was always large and ended with a flourish and she underlined her name. I suppose she really was decent and wanted to try and make up for my father’s mistakes. I suspected I might even like her, but I never seriously considered making the trip. I felt it would be disloyal to my mother, who needed all the allies she could get.

When I was seventeen, my mother got a good job as principal of a high school in Michigan, a small town outside of Kalamazoo. She was excited for the opportunity, and it paid well, too. We would buy a house, and I’d do my senior year there. It was time to put Illinois behind us, she said, and embrace change, grab hold of a new future. The past, she said, did not have to have a hold on us. The past was a foreign country, she added. We did not need to visit the past.

We loaded up a U-Haul and started north on a day when rain drizzled at first, but the sun peeked out when we were just south of Chicago and making the turn east to eventually cross into Michigan, a new frontier for both of us. Even the charcoal clouds cleared away to reveal a sapphire sky.

We stopped for gas in northern Indiana, not far from the Michigan border. I pumped the gas while my mother leaned against the car and stared at the highway, in the direction of Michigan. She even pivoted some, to make sure she could not look back in the direction we’d come from. As I put the gas nozzle back into the pump and capped the gas tank, I noticed she looked down for a moment and wiped her cheek lightly with a hand. I waited, until she turned and smiled, and we got in and merged with traffic headed north.

After a few miles she told me that Grant Molloy had recently killed himself, had shot himself with his .38 while sitting in his car in his garage. I thought immediately of Millie, and the goofy son—Raymond. It took a moment to recall his name. We went on a few more miles in silence.

“Why do you think he did it?” I finally said. “I mean, he always seemed like he was confident. Even fearless.”

She glanced at me but said nothing for another mile or two before speaking softly.

“I guess he couldn’t take things anymore.” She wiped a tear.

“What things?”

She shrugged and patted the steering wheel lightly a couple of times.

“Choices, I guess,” she said quietly. “The endless, tough choices life always hands us.”

She glanced at me and smiled and then patted my shoulder. I looked out my window for a while and saw a sign that said Welcome to Michigan. It kind of felt like we’d survived a war and were going to a new home where the past didn’t matter anymore and the possibilities—choices—were endless.

About the Author

Michael Loyd Gray is the author of six published novels. His novel The Armageddon Two-Step, winner of a Book Excellence Award, was released in December 2019. His novel Well Deserved won the 2008 Sol Books Prose Series Prize, and his novel Not Famous Anymore garnered a support grant from the Elizabeth George Foundation in 2009. His novel Exile on Kalamazoo Street was released in 2013, and he has co-authored the stage version. His novel The Canary was released in 2011. King Biscuit, his Young Adult novel, was released in 2012. He was the winner of the 2005 Alligator Juniper Fiction Prize and the 2005 Writers Place Award for Fiction. He was full-time lead faculty for creative writing and American/British literature at Aiken Technical College (South Carolina). His stories have appeared in Alligator Juniper, Arkansas Review, I-70 Review, Flashpoint!, Black River Syllabary, Verdad, Palooka, Hektoen International, Potomac Review, Home Planet News, SORTES, The Zodiac Review, Literary Heist, Evening Street Press & Review, Two Thirds North, and Johnny America. He earned an MFA in English in 1996 from Western Michigan University, where he was a Phi Kappa Phi National Honor Society scholar (3.93 GPA). He was also a fiction editor for Third Coast, the WMU literary magazine. At WMU, He studied with MacArthur Fellow Stuart Dybek, Writer in Residence at Northwestern University, and novelist John Smolens, former head of the MFA program at Northern Michigan University. He earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Illinois, where he studied with Flannery O’Connor Award winner Daniel Curley. For ten years, he was a staff writer for newspapers in Arizona and Illinois.

Michael Loyd Gray is the author of six published novels. His novel The Armageddon Two-Step, winner of a Book Excellence Award, was released in December 2019. His novel Well Deserved won the 2008 Sol Books Prose Series Prize, and his novel Not Famous Anymore garnered a support grant from the Elizabeth George Foundation in 2009. His novel Exile on Kalamazoo Street was released in 2013, and he has co-authored the stage version. His novel The Canary was released in 2011. King Biscuit, his Young Adult novel, was released in 2012. He was the winner of the 2005 Alligator Juniper Fiction Prize and the 2005 Writers Place Award for Fiction. He was full-time lead faculty for creative writing and American/British literature at Aiken Technical College (South Carolina). His stories have appeared in Alligator Juniper, Arkansas Review, I-70 Review, Flashpoint!, Black River Syllabary, Verdad, Palooka, Hektoen International, Potomac Review, Home Planet News, SORTES, The Zodiac Review, Literary Heist, Evening Street Press & Review, Two Thirds North, and Johnny America. He earned an MFA in English in 1996 from Western Michigan University, where he was a Phi Kappa Phi National Honor Society scholar (3.93 GPA). He was also a fiction editor for Third Coast, the WMU literary magazine. At WMU, He studied with MacArthur Fellow Stuart Dybek, Writer in Residence at Northwestern University, and novelist John Smolens, former head of the MFA program at Northern Michigan University. He earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Illinois, where he studied with Flannery O’Connor Award winner Daniel Curley. For ten years, he was a staff writer for newspapers in Arizona and Illinois.

Prose

Excerpt from novel-in-progress Plastic Soul: On the Destructive Nature of Lava James Nulick

About the About Mary Burger

Ellipse, DC Denis Tricoche

Excerpt from My Women Yuliia Iliukha translated by Hanna Leliv

In the East John Gu

Fire Trances Iliana Vargas, translated by Lena Greenberg and Michelle Mirabella

Excerpt from Concentric Macroscope Kelly Krumrie

Autumn Juan José Saer, translated by Will Noah

Pen Afsana Begum, translated by Rifat Munim

The Game Warden Michael Loyd Gray

Current and Former Associates William M. McIntosh

Take Care Laura Zapico

Poetry

I am writing the dream Stella Vinitchi Radulescu, translated by Domnica Radulescu

and finally, life emerging

and the night begins

Letter to the Soil Skye Gilkerson

A Flight Adam Day

The World Ariana Den Bleyker

What We Held in Common Justin Vicari

The Shame of Loving Another Poet

How to Keep Going Rebecca Macijeski

How to Lose Your Fear of Death

How to Paint the Sky

Eternal Life Cletus Crow

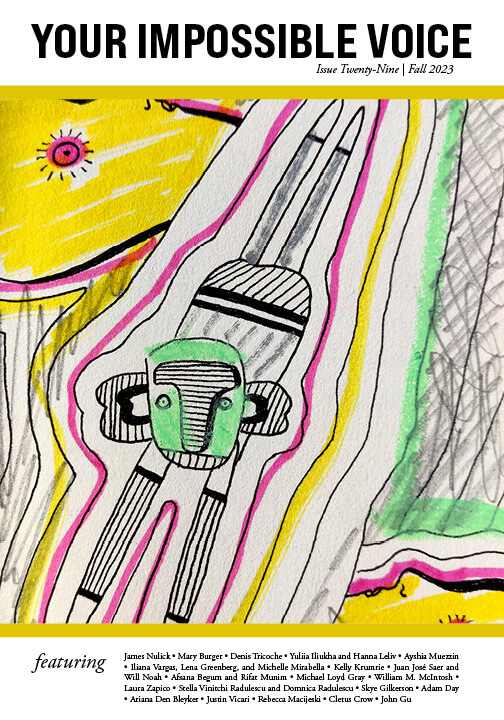

Cover Art

Deep Dive Ayshia Müezzin