Issue 29 | Fall 2023

Fire Trances

Iliana Vargas

Translated by Lena Greenberg and Michelle Mirabella

I am illuminated by holy light fired at me from another world.

I see what no other man sees.

—Philip K. Dick

1. Lucille and Violette

“Mais, qu’est-ce qui se passe avec toi, Violette? Ce que tu dis n’a aucune sens… c’est une folie de t’écouter.”[1]

Violette puts the ashtray back on the table, placing it alongside one of her books, and cleans up the cigarette butts and ash that were knocked to the floor when Lucille abruptly stood up from the couch.

“Stop talking to me in French, Lucille, as if you had no clue who I was, or what’s going on. You’re the one who went to get me from the convent. You’re the one who paid for all the damage the Mother Superior and her following say I caused, even when you knew it wasn’t true. Take another look at me; look at my trembling body, my transparent skin, my wounded tongue, and tell me again that all of this isn’t insanity. It’s pointless fighting over who’s right: it’s not about figuring that out, or making it up, but rather about accepting things, how things are, what’s there. You say it’s my delusions; that the tragedy, the illness … despite you being there with me the first time it happened. I’m telling you, I wasn’t seeking this out, I didn’t even know it existed, and That chose me anyway. If you want me to keep talking to you, make an actual effort to communicate.”

Lucille paces back and forth between the window and couch until she stops, gazing at the slime left by a snail on the cement fountain in the garden.

“Cela? Cela? Qu’est’ ce que tu vois dire avec ‘Cela’?[2] Is there no way to name That in your Spanish language?”

She asks the second question as if talking to herself, her voice lowered, softer, in unwitting acknowledgement of the Spanish she was speaking. Lucille lifts her gaze from the snail to look at Violette. But not at all of her: her eyes linger on Violette’s exceptionally long hair, almost fully grayed. If Violette weren’t her sister, she would be hard pressed to believe her to be twenty years old.

“That is not a name; That just is, Lucille, and it’s present, it’s coming to tell us what you wanted to know.”

Violette looks at her hands as if they belonged to someone else: the small blotches that hadn’t been there just a few months ago. The wrinkles. The marks. Traces of the fire on her palms, branding her with proof of the first time it happened … the time she had the vision of Zahana.

2. Zahana

The rain was pouring down as if the Earth was in want of soothing its red-hot core. The dogs grew quiet little by little, subdued perhaps by the strident, ever-closer thunder, and I watched as the water pooled on the roof of the house next door. I often spent long hours gazing out at that rooftop from Laila’s room. That was my favorite part of the Manor. I loved going up there after wandering the endless corridors leading to the rooms that had once belonged to the abbess of Pretzi. I always had trouble believing that that place, now so cozy and cheerful, had once been a kind of prison. Most unfathomable to me was that its inhabitants—almost all women—had chosen to submit themselves to that cloistering to feel closer to God, when God was supposedly everywhere. Now I understand everything better, or worse, I don’t know. Whenever we’d go there on vacation you’d ask me to come down and help you look for ladybugs in the garden, but I took pleasure in the scent of the dried flowers and oils that Laila had left in her room, as if she wanted us to remember her by that aroma, and not by the smell her body gave off when we found her full of worms beneath the bed. Don’t look at me like that, Lucille, it wasn’t Laila I wanted to talk with you about, but rather the view from the window in her room, which that morning showed me more than just the moss and those budding, small wild plants taking over the gray stone perimeter wall and the cracked ground.

I recall imagining how the water would seep through the fissures, forming thin drops that trickled down onto the rusted furniture belonging to that place whose inhabitants we never met. Or how there would be so much water that the roof couldn’t bear it, finally falling apart. Or how, in the best of cases, a small pool would form where I could jump in as soon as the storm was over and the air began condensing, so hot and thick that I’d have to breathe through my mouth, like the fish held in buckets on the lakeshore. Perhaps because I was pondering the feeling of suffocation I began to feel that the air wasn’t fully reaching my lungs. That’s when I saw her, under the water. At first I thought I was just seeing one of the plants moving with the cadence of the rain, but then I saw her eyes, her face, her hair floating on the surface, her suffocated look. She’d poisoned herself. Her name was Zahana, and she’d swallowed a belladonna berry extract that she herself had prepared. But why, at sixteen, did I have to know that? I was disturbed, not just by the morbid scene and the sensation of pain as if it were my own, but by her clothes that billowed in the water: she was dressed in a tunic like those worn in the Pretzi abbey back when it was still inhabited. I was at a loss as to how this information had entered my mind or my entire body; as to why, when I saw her, I knew what this young woman had experienced. I began to feel something boiling within me, but I couldn’t manage to discern if that something was hers or mine: my joints and muscles burned as if hundreds of spiders were biting the flesh beneath my skin. I could no longer feel the weight of my bones, and a ring of fire engulfed the water, transforming it into a stone room. I then discovered that I was there, not in body, but in shadow with Zahana, and all I could see was what she could from her unconscious mind: the tunnel that led me to her epiphany as she prayed in ardent concentration. In that moment it became clear to me why it’s said that one can speak with God, and why, during that trance, other presences can also seep in with their voices, eyes, and forms all incarnated as one sole presence whose name inhabits many languages but that no one wants to utter. And I decided to neutralize it and call it That. Zahana was praying with the fervor of those who have lived for salvation. It seemed the words found flesh in her tongue and lips, but upon leaving her mouth, the sound was not that of her voice nor of the litanies written in her holy book. No. She’d left the book spread open before her as she knelt in front of the bed, and she would occasionally glance down at the verses on its yellowed pages, although it was quite clear that she had each prayer committed to memory. However, something within her body suspected that what she was saying was not what her heart vehemently asked of her, as the words were different, not her own: they were spit forth unnaturally by her throat. How could I make her see that what was seeming to fail her was not her memory but rather the refuge of her God? He had evidently abandoned her, leaving her in the hands of that whose divinity belongs to another Kingdom. Yes. It was the Devil. Or one of His emissaries.

How do I know? Due to one of my blunders: as the hypnosis seemed to drag Zahana away from this world, jerking her back and forth with increasing violence until her body bashed against the sharp rocks of the wall, I sensed that her voice was not her own and that the tongue in which she was speaking, ensnaring her more and more, could only have its origins in the dreams of Hell. When I realized what was happening, I rushed at her in my shadow form and covered her mouth. I felt a sweet, feverish pain that numbed my hands. I returned abruptly to my body behind the window in Laila’s room. Trembling, I screamed uncontrollably. I recall not recognizing the sounds that were leaving my mouth, but what truly frightened me was the burning sensation on my hands. The rain had subsided, and I suppose the sound of my screams reached the garden, because you came running in, beside yourself. I’ll never forget the expression on your face when you saw me. The way you began to cry, No, no, no, no, no, no!, covering your ears as I spouted those sounds that wrung my throat and split my lips, leaving me breathless until I finally passed out. I don’t know how you managed to carry me out of there without getting burned yourself. Most importantly, I don’t know how you decided that, by shutting me away in a place like Santa Cecilia, I would be able to recover from what you called fires of the soul. How could you not have known that a convent is the most coveted fuel for any fire? Especially that of the Devil.

3. The Final Vision

“And so now you’re claiming it’s my fault you can’t tell the difference between the Devil and your own insanity?”

“No, Lucille! Insanity is part of the human condition. It comes and goes from our bodies to drive them to a premature state of decay or bring them to a certain lucid maturity. The Devil doesn’t need to play those kinds of games for us to give Him what He wants … You should have listened to His message from the start.”

“What does He want? What message? Je ne sais pas pourquoi je vous entends …”[3] Lucille traces each of her fingers obsessively, as if fearing she might forget their shape. It’s been a while since she’s needed this soothing motion to temper the anxiety beginning to grip her. She stares at the green floral design on the hexagonal tiles that run along the white walls. What wouldn’t she give right now to be a flower or a plant, anything with a conscience unburdened by judgment. Anything whose deeds, as obscure as they may seem, are free of consequences.

“Yes. His message through your dreams. That’s why you wrote them down. You would say you didn’t know why, and then you’d throw them out or burn them. But you understood it all so well that at one point you gave me one, promising that someday I too would be able to speak with Him, and that He would show me images that, as strange as they might seem at first, were ultimately beautiful, like the one you transcribed here, look.”

Violette opens the book that she’d left on the table, pulls out a long, loose page with creases well-marked by the years, and spreads it out carefully so as not to smear the ink that she’s traced over each letter countless times. The margins are dotted with a smattering of drawings depicting birds, amphibian animals crowned by insects, and even a mix of both, but here the ink has faded over time, and it’s become difficult to make out the exact shapes. Violette offers Lucille the page, but Lucille looks at her in astonishment, her eyes moist, and shakes her head, refusing to look at it. And so Violette begins to read the text aloud:

THE FINAL VISION

Tonight, as I slept, a giant hand took my head and dragged it brazenly across a piece of paper, using it as a pen, pressing my eyes so close to the ink (which was in fact a mixture of my blood and scalp) that I could not discern what the hand was writing.

Each stroke tried to put into words what my voice could not utter but my tongue was thinking. And a thinking tongue is a bold and insatiable thing, like everything it devours in its hungry path toward the celestial infinity.

The tongue was the heavens, but the heavens, far from blue, were an intense shade of ruby that lit up the entire Earth. Day and night were no more. The line separating the ocean and all the features of the land was no more. The apocalypse had come in the form of a raging storm, unleashed by the rage men had sown among all their descendants, relentlessly, with no pause to look at one another. To think. To recognize themselves in the Other. No. Rather, they had butchered, beaten, poisoned, and bled their brothers. They had built walls and barriers that were not only physical, but also brutal systems based on racism, violence, and the appropriation of a space that was no one’s to claim. They had stopped sharing food and shelter, having forgotten that if food and shelter existed at all, it was only because humans had once worked together to nourish and house themselves and one another. They had massacred women with particular cruelty, having forgotten women’s sacred connection with the Earth. There was no way back. No repentance. No forgiveness. It would not be God, in any of His manifestations, but rather the Devil, in any of His manifestations, who would avenge what had been squandered. Because a world full of minds uninterested in the pursuit of knowledge, in making sense of the unknown, is a terrible waste. There’s no value in a body whose sole purpose in life is to destroy the Other. That’s what divine power, whatever be its face, is for.

And then stones began to rain down from the heavens, but not as prophesied: these were not stones of fire or salt, nor fragments of colossal meteorites, but stones of amber. The ruins of a mountainside cemetery in the south of the world. For the first mountains to shelter men were in the southern part of the Great Continent, and now those same mountains would be tasked with burying them.

Everything shook mightily, and soon nothing was left but a creature of cloud and fire. The light stung its eyes. The ruins were the traces of what was left in the aftermath of the silence. The Earth went still; gone were the vibrations that had once been everyone’s lullaby. Silence overtook the bodies. Nothing could flow any longer, for there was no underlying force to drive any movement. The last stones falling from the sky were the outer layer of what until that moment had inhabited the air, out of sight of all human beings, but not of all living beings.

Silence would absorb everything because no longer would anyone be able to question anything. Salvation would only come for the one able to bring light and sound to the newly formed cosmic void, still latent, by asking the right question.

“I’ve read it many times, especially while I was shut away in Santa Cecilia. Those kinds of texts gave me comfort there. Little by little I discovered others, and Hildegard and Sor Juana stayed with me. I found the Primero Sueño in the convent library, half hidden in the astrology section, and asked one of the superiors why they had put it there, but she looked at me disapprovingly and tried to snatch it from me, saying that one must have a certain level of understanding to read such things. And of course that didn’t answer my question; it only increased my curiosity. It’s true that the first time I read it I didn’t understand much, and I assumed this was what the superior meant by ‘certain understanding.’ And yet the more I re-read it, using dictionaries and science and philosophy books, the more I felt I was uncovering the secrets of Sor Juana’s mysterious language and dreamlike poetry. I gradually came to understand that as surreal as they may seem at first, the worlds of dreams and epiphanies hold the secrets of the future and the past, and we have to learn to transform and translate them into earthly language to allow for other ways of understanding each other, even if they don’t seem to be the right ones. Even if nothing we do seems like what it should be.

“Now, please explain just this, Lucille. Why did you shut me away in Santa Cecilia? Why weren’t you the one to teach me to read these dreams and make sense of the language of God and the Devil if they complement, rather than contradict, each other?”

Lucille once again approaches the window. The afternoon is unfolding, enveloping every fiber of everything alive outside in its majestic light. The sky is beginning to turn red and expand, as if someone were tugging on its ends in all directions to stoke a sort of outdoor furnace. The birds have taken refuge in the treetops and the crickets vibrate between the stones without making a sound. Dogs venture out onto the sidewalks and wander the empty streets, but don’t dare to bark, or even howl. The afternoon hangs, immense, strangely reddish, as if prevailing over day and night. It streams through all the windows and roofs and walls of all the world’s houses, buildings, museums, movie theaters, playhouses, bookstores, schools, offices, restaurants, cafés, and bars. The wind taps pebbles against the window through which Lucille is watching the sky grow redder and redder. Only then does she turn to Violette, who covers her mouth to stifle a scream when she sees her sister’s eyes glinting with the same crimson that is seeping inside until it floods everything in the house. Lucille, smiling like never before, approaches Violette ever so slowly, then grabs her by the back of her neck and drags her to the window.

“You already said it, Violette. Your whole being was raw fuel. All you needed was a spark to bring about the trance, to awaken the desire to know what lies in the silence of both God and the Devil, the silence you call That … An unrecognizable, mysterious silence. Which is why the mystery is the key to what’s worth discovering, as you’re about to witness. Don’t try to understand it; you’ll need neither understanding nor body in your new essence. Come closer. Look. Don’t fear the fire. Tell me what you see behind these infinite flames that have already begun to devour us with their divine tongue.”

About the Author

Iliana Vargas is a Mexican author and graduate of UNAM specializing in speculative fiction. She has authored several books of stories including Joni Munn y otras alteraciones del psicosoma, Magnetofónica and Habitantes del aire caníbal. Her most recent book, Yo no voy a salvarte, was published by EOLAS Ediciones in 2021. Her work has appeared in translation in Latin American Literature Today and Exchanges: Journal of Literary Translation, among others.

Iliana Vargas is a Mexican author and graduate of UNAM specializing in speculative fiction. She has authored several books of stories including Joni Munn y otras alteraciones del psicosoma, Magnetofónica and Habitantes del aire caníbal. Her most recent book, Yo no voy a salvarte, was published by EOLAS Ediciones in 2021. Her work has appeared in translation in Latin American Literature Today and Exchanges: Journal of Literary Translation, among others.

About the Translators

Lena Greenberg is a translator working from Spanish and Catalan into English and occasionally English into Spanish. Commercially, her translation expertise lies in government and politics, legal documents, and marketing materials. She holds an MA in translation and interpretation from the Middlebury Institute of International Studies and a BA in linguistics from the University of Pennsylvania.

Lena Greenberg is a translator working from Spanish and Catalan into English and occasionally English into Spanish. Commercially, her translation expertise lies in government and politics, legal documents, and marketing materials. She holds an MA in translation and interpretation from the Middlebury Institute of International Studies and a BA in linguistics from the University of Pennsylvania.

A 2022 ALTA Travel Fellow, Michelle Mirabella is a Spanish-to-English literary translator whose work appears in the HarperCollins/Amistad anthology Daughters of Latin America, The Arkansas International, World Literature Today, Latin American Literature Today, and elsewhere. A finalist in Columbia Journal’s 2022 Spring Contest in the translation category and short-listed for the 2022 John Dryden Translation Competition, Michelle holds an MA from the Middlebury Institute of International Studies and is an alumna of the Banff International Literary Translation Centre and the Bread Loaf Translators’ Conference.

A 2022 ALTA Travel Fellow, Michelle Mirabella is a Spanish-to-English literary translator whose work appears in the HarperCollins/Amistad anthology Daughters of Latin America, The Arkansas International, World Literature Today, Latin American Literature Today, and elsewhere. A finalist in Columbia Journal’s 2022 Spring Contest in the translation category and short-listed for the 2022 John Dryden Translation Competition, Michelle holds an MA from the Middlebury Institute of International Studies and is an alumna of the Banff International Literary Translation Centre and the Bread Loaf Translators’ Conference.

Prose

Excerpt from novel-in-progress Plastic Soul: On the Destructive Nature of Lava James Nulick

About the About Mary Burger

Ellipse, DC Denis Tricoche

Excerpt from My Women Yuliia Iliukha translated by Hanna Leliv

In the East John Gu

Fire Trances Iliana Vargas, translated by Lena Greenberg and Michelle Mirabella

Excerpt from Concentric Macroscope Kelly Krumrie

Autumn Juan José Saer, translated by Will Noah

Pen Afsana Begum, translated by Rifat Munim

The Game Warden Michael Loyd Gray

Current and Former Associates William M. McIntosh

Take Care Laura Zapico

Poetry

I am writing the dream Stella Vinitchi Radulescu, translated by Domnica Radulescu

and finally, life emerging

and the night begins

Letter to the Soil Skye Gilkerson

A Flight Adam Day

The World Ariana Den Bleyker

What We Held in Common Justin Vicari

The Shame of Loving Another Poet

How to Keep Going Rebecca Macijeski

How to Lose Your Fear of Death

How to Paint the Sky

Eternal Life Cletus Crow

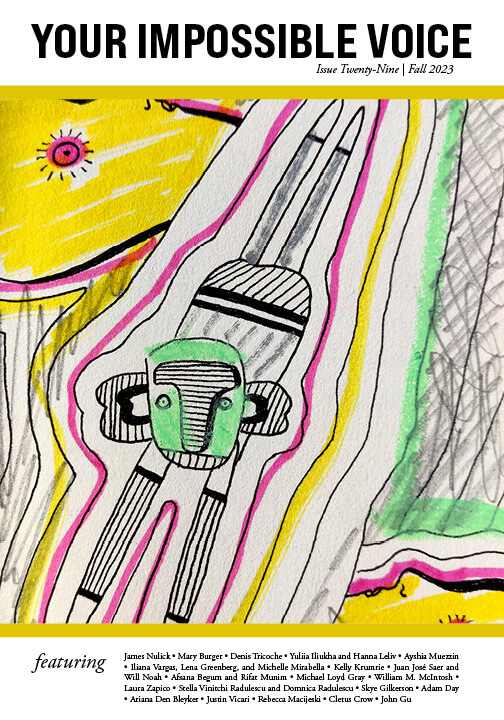

Cover Art

Deep Dive Ayshia Müezzin