Issue 29 | Fall 2023

Pen

Afsana Begum

Translated by Rifat Munim

Had anyone ever heard of the spirit of a discontented ghost wandering through the packed streets of an old book market when there were so many other places to haunt people? Just like there were bookworms, there were book ghosts, too.

A long time ago, it so happened that a pen got stuck to my hand. It was by wearing a long-sleeved kameez that I somehow managed to keep it concealed from others. But for how long? I tried everything to yank it out of my hand, but it remained stuck along the fate line. Finding no other way, I decided to see the man I had bought it from.

The stall I had bought the pen from was deep in the heart of the old book market. I was ever-addicted to exploring this market on my way back from work. The distinctly musty smell hanging in the air of this market never failed to leave me inebriated. I was buying new books constantly. Even then, whenever I was passing by stacks of old books, I’d invariably be struck by the thought that perhaps gems of many sorts lay hidden within them, uncared for, so maybe I should explore them a bit more; it was as though glowing diamonds were calling me from within heaps of coal. That day was no different, and on my way back, I jumped down from the rickshaw and walked straight into the market crammed with stalls and people and street vendors.

Near the heart of the market, I dropped into a familiar bookstall. While I was browsing around the stall looking for books that gave off a musty smell, my eyes caught a stall selling pens right across the alley. With rows of pens arranged in a couple of showcases, the stall owner sat with his legs crossed. The man didn’t seem interested in selling his wares. Placing a long ledger on his lap, he was intently jotting something down. The pens in his stall didn’t look like anything I had seen before—their shapes and colors were entirely different. A strange thing happened right then. I felt a strong pull towards the stall—as though the shop were a huge piece of magnet and I were a small slab of iron. Like a machine, I put Virginia Woolf’s greatest nonfiction book back. As curiosity got the better of me, I asked the bookstall owner if there had been a pen stall there before. “No, Apa, there was no such stall before. Now a man is sitting there with his strange collection of pens. His sales are very poor, yet he opens his stall every day.” “Who’d visit this old book market to buy such tacky pens,” I sneered. Besides, the pens looked really old, as if they had got a thick coat of rust from lying in a corner for too long. But the stall was still pulling me towards it.

The man was so engrossed in jotting down numbers that he didn’t look up from his ledger. He showed no interest in selling pens. Quite irritated, I called to him, “Hi there. Can I take a look at the pens?”

Lifting his head slowly, he peered at me over the rims of his glasses. He seemed to be thinking it over in his mind as to whether he’d sell his pens to me or not. I was peeved, yet I could not budge an inch, as if my feet were glued to the spot, quite literally. After looking me up and down, he said, “Why do you need a pen?”

I stared into his eyes, my mouth gaping, as I failed to make sense of his question. How come a man who had set up a pen stall didn’t know why a pen was needed? “To write,” I said, but I felt so riled up inside that I shot back, “What else do you think we do with a pen?” Pushing the rims of his glasses further down the bridge of his nose, he peered at me again, got up from his chair, and opened the glass doors to display his collection.

“Of course you will write, but I am just wondering what exactly it is that you’ll write.”

Was he crazy? I’d write whatever I wanted—maybe a grocery list or an epic. What the hell did he care?

“Yes, yes, you may write a whole lot of things with your pen, like poems or song lyrics or grocery lists. Is there anything particular that you want to …?”

I cut him short. “What’s your problem? Can’t I write all of these different things with the same pen?”

The man gave me a cold-eyed stare, as if I’d said something outrageous. With disappointment gleaming in his eyes, he picked the pens up, one by one, before describing their functions.

“Look at this one—it is like any ordinary ballpoint pen. This one is for tasks like grocery lists and signatures on documents. But this one is a bit better and you can use it in your office, but not for tasks that involve writing of some importance. If you want to write long reports or project proposals, you should use this one. For purposes of study, there are different pens which are on that …”

I just about hit the roof. Different pens for different tasks. That was a veritable scam! I was sure I was being taken for a ride. But could he read my mind? Otherwise, why did he stop before finishing his pitch? With a pallid face he said, “You don’t need pens anymore, do you?”

“No, please carry on. I’m listening.”

Before he resumed his speech, he picked up a new pen. “As I was saying, this one is for the purpose of study. This one, I sell at a special discount to students. Do you need one of these?”

“Not really. I’ve finished my studies. I have a fulltime job now.”

“I see. What kind of work does your job entail?”

“That piece of information is redundant because I am not going to buy a pen for any office work.”

“Well, then maybe for little tasks at home, right?”

Before I could say yes, my eyes fell on a few pens arranged in a showcase on the left side. They shone in diverse colors and shapes. I gazed at them in wonderment. His brows knitted together when he noticed how amazed I was by those pens. Pushing his glasses up, he said firmly, “Those are not for ordinary tasks.”

“Who knows what stories he’ll come up with this time?” I thought to myself. What if he said those were not for me? But deep down, I knew I wanted one of those. “What are those pens for?” I said.

“Those are for writers, poets, playwrights, and essayists. Using them for other kinds of writing may create problems.”

“What kind of problems?”

“Maybe the writing will be illegible. Every pen should be used to carry out the particular task it is meant for. Only then does it work perfectly.”

“Okay, but what if I want to buy that maroon pen?”

The light above the showcase glinted off the pen I pointed at. “That one is for writing stories. Do you really want to take the maroon one? Listen, buying one of these pens means letting other personalities rise up in you.”

“What do you mean?”

“Let me explain. You are standing here in front of me—now you are your own person. But when you write a story using the maroon pen, a different person will rise in you. As you enter the minds of other characters, you’ll find yourself immersed in them for quite some time. Aren’t you thus becoming a different personality, at least for a while?”

I was not certain if the man was dissuading me from buying the pen despite being the seller. The thought that maybe I was not competent enough to own the pen left me distressed. But the man seemed to have an inkling of what my mind was going through. He said, “Take it, then. It won’t be difficult for you to figure out whether it’s meant for you or not.”

He put the pen in a case and handed it to me with a mysterious smile. As I was in a hurry, I made my way through the market crowd as quickly as I could. Once back on the street, the smell of daal puri, a lentil-filled deep-fried flatbread, assailed my nostrils; I remembered I’d bought two puris but forgotten them at the pen stall. I hastened back to the stall to find the owner waiting for me. He stood up and held the parcel of puris out to me. His smile had turned more mysterious than before. “I knew you’d come back. If that pen works out for you, you’ll have to come back to this stall,” he said.

I didn’t know why, but his mysterious smile made me feel uncomfortable. I looked away and cast a look at the showcase on the left. How strange! Had the pens looked so simple minutes ago? I could not contain my astonishment, so I wanted to know if these plain-looking pens had been there before.

The man laughed out. “Of course they were. My stall is not going to change in five minutes,” he said. “They look different as dusk falls. Also, all the other pens look pale to the person who buys the one that you have.”

“Is that so?”

“Yes. Why, compared to storytelling, grocery lists are pretty ordinary! Aren’t they?”

“Indeed!”

“One more thing. I think your pen will deliver. Otherwise, all the other pens wouldn’t appear so ordinary to you. Which means you’ll have to come back.”

I didn’t quite like his last words, or the mysterious smile that clung to his lips. It was not like I’d leased my property to him; I’d just bought a pen. Why on earth should I come back to this place? I brushed his words aside and left immediately.

Occasionally, I took the pen out of its case to look closely at it. One day, it occurred to me that if I used it, I’d have to tell a story. Why not try, then? But what would I write about? That was the question.

Different thoughts ran through my mind: Why not write about the experiences I had gathered in life? When I was a child, I knew a kid who, having been bitten by a dog, died a slow, painful death for lack of treatment. The imam of the local mosque had given him water purified by recitation of the Quranic verses and his parents were certain that he’d recover fully if he drank just one gulp of that water. Eventually, the boy died of hydrophobia. So why don’t I write about that boy?

Accordingly, I put pen to paper and wrote the story. The pen ran too fast. When I was pretty impressed with its performance, to my utter shock, I found it stuck across my palm. I couldn’t recall if I had kept any tube of superglue somewhere on the table. I did my best to wrench it away, but nothing worked. I had no clue as to what I should do, nor did I know whether anyone had ever faced an issue like this. My office would be closed for the next two days. So I neither stepped out of the house nor shared my ordeal with anyone in the family. What would I say if anybody wanted to know why I bought such a pen and why I chose to write such a story with it? That I nurtured a vast world of my own in the deep recesses of my mind would be out in the open if I explained myself. I passed my time in fear. Despite the summer heat, I put on a long-sleeved kameez with a heavy and wide orna so that no one could get a glimpse of my hand.

The pen was making my life miserable, not because I had to go about my daily activities while it was fixed on my hand, but because many yet-to-be-expressed ideas were crowding in my head. I realized there was nothing more painful than letting an unarticulated story rest in some corner of your mind. The strange thing was: whenever the ideas were jostling for an outlet, the palm to which the pen clung itched badly. The itching lessened only when I wrote a paragraph or two, but the moment I stopped, it started again. But what could I do about it? I couldn’t just shut the door and start writing my stories, shrugging off all family responsibilities. So when everyone in the family went to bed at night, I sat down to write. The more I wrote, the more the pain eased. But the question gnawing away at me was: How to wrench it off my hand? I couldn’t possibly live the rest of my life with a maroon pen stuck across my palm. Not only was I unable to do any of the chores properly, I also had to eat with a spoon, which raised a question or two. The worst part of this whole experience lay in the tension arising out of my two conflicting personalities. How could I get it across to others that a new person was emerging out of my old self? Would they recognize the new “me”? What if they jumped to a horrible conclusion, having failed to understand my transition? Only one line from a Tagore song kept swirling in my head: “I don’t know why my soul rose like this after all this time?”

I was too scared to get any sleep for two nights in a row. I was furious with myself for having bought the pen despite the stall owner’s warnings. Now, I had no other option but to see the man again.

On the first weekday, after work, I headed straight to the old book market. The man was poring over his long ledger. There were hardly any customers, yet he studied his ledger with such attention that it did ruffle my feathers! When I stood in front of him, he took his glasses off. His impassive countenance was replaced by a sense of familiarity. As a smile spread across his face, I realized he’d been waiting for me.

“You must be in trouble?” he said, grinning ear to ear. As if he were beside himself with joy because I was in trouble. I was too outraged to speak. But the man went on, “It’s got stuck onto your palm, right? There’s nothing you can do about it. Now, there is no alternative other than to keep writing.”

I totally lost it.

“You knew it! You knew that I’d be facing this, didn’t you? You put me through this deliberately.”

“What’s the big trouble? Just a little bit of itching. You must have noticed by now that the more you write, the less you itch, right?”

The man looked calm. As if he’d fulfilled his duty by sharing this vital piece of information.

“Why did you do this to me? How could you not think about my suffering?” I yelled.

“Listen, I warned you about this. I said this was no normal pen. Didn’t I?” the man said, looking serious.

“Yes, you did. But you didn’t spell out that the pen would be plastered across my palm.”

“That’s because it is not possible for me to know everything beforehand. A pen may or may not cling onto one’s hand. It acts differently on different people.”

Even though the man seemed to soften his tone, I was clueless as to how he could treat this whole thing so nonchalantly.

“So how can I get rid of this pen? There must be something you could tell me,” I enquired, hell-bent on finding a solution.

“To tell you the truth, there is no easy way! The pen will die when your hand dies. The creation of stories is a never-ending process. So your hand will itch as ideas for your stories continue to pop into your head. But yes, there may still be one solution.”

I gazed at him, my eyes gleaming with curiosity.

“What is it? Please tell me! I want to be rid of it. I’ve gotten too tired in just three days!”

The man gazed back at me and looked serious again. “Your pen will fall away when you write something that contains seeds,” he said.

“What? Seeds in stories? Are stories like fruits?”

“Yes, they are. A thousand stories can be created out of just one powerful story. Which means a line from your story can give birth to numerous lines in someone else’s mind. Who knows, maybe your pen will get stuck to their hand! Isn’t that the whole purpose of writing a story? Why create stories that do not inspire others?”

I was listening to him silently. The man took a deep breath before speaking again. “Only when there is a story from which can spring numerous stories will you be rid of this pen.”

“How will I recognize a story like that?”

“You don’t have to recognize anything. The person who reads will know and recognize,” the man said gravely. As if he had said all there was to say. He put his glasses back on and picked up his ledger. He seemed to be getting down to business. After getting me in trouble, he spouted utter nonsense, not to mention the cold shoulder he was giving me now. As I was about to leave, he lifted his eyes and said, “The day your pen inspires someone, you’ll see that all the veins on their hand are turning green, that they’re bursting with energy and exuberance. The weight of your pen, you’ll feel, is shifting from your hand to theirs. From one will arise many pens to spread out across many green hands.”

While he declaimed, he was, it seemed, being transported to a different world. His utterances came out like the recitation of a poem. He looked almost like a magician. As if he were spinning a web of illusion around me. I decided to give him the slip before he could cast a spell over me. I turned around and faced the much familiar bookstall. I made towards the stall.

“Shafiq bhai, has Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own been sold already? Remember, I was flipping through the pages that day?”

“No, Apa. I put it aside for you.”

As I was about to pay him for the book, he gave me a startled look.

“What’s this, Apa? What’s there in your hand?”

Before he could utter another word, I handed him the cash and disappeared into the crowd.

I continued writing. Since the pen wouldn’t disentangle itself from my hand, I wrote whenever I had some spare time. Manuscripts were piling up in my room. At one point, I sent out a couple of them to publishers. Why wouldn’t I? The pen stall owner said that the only way I could reclaim my freedom from this pen was by inspiring someone and thus paving the way for more stories.

As my stories were being put together in collections by publishers, I felt like tailing a reader—I became desperate to know whether my stories were sweeping them away; whether my stories were spawning fresh, creative ideas; whether the veins on their hand were turning green. But I couldn’t bring myself to follow a reader.

Despite my reticence about my stories, my family members somehow learned about them. Not too surprisingly, they were alarmed to discover them. So they bombarded me with questions: What have you written about and why? Whose stories are these? Do you really know people like them? Are you like them? Why didn’t you tell us about any of this before? I couldn’t come up with any answers to pacify them. I chose to stay silent instead.

Meanwhile, the pen continued triggering the itching from time to time, so I continued writing. I discerned, gradually, that it was not just me; a whole lot of other people had pens stuck to their hands too. Surging with pride, many of them were displaying them to others. In fact, none of them were furtive about it like I was. So many people set about writing so many stories. I saw the veins on my own hand turning green umpteen times. I slid my hand inside the sleeve to keep the veins out of sight, just like I did with my pen. I knew that there would be quite a ruckus if certain people got wind of my green veins—especially those who thought I was impassive as a doll, those who took me for a woman with no creative thought or opinion of my own. But soon, I was aware of another change: As I went on writing more and more stories, the green of my veins was merging into the brown tone of my skin. I was speechless with sheer joy.

I hadn’t stopped visiting the old book market, though. At times, I discovered myself in front of the pen stall. When I saw someone picking a pen from the showcase on the left side and toying absently with it, I felt happy. But when I saw them finally buying it, I became ecstatic. The stall owner spotted me once, and, chuckling quietly, he said, “Apa, what do you look for, standing there like this?”

“So many people are walking the streets with pens stuck on their hands these days. Those from far-off places are not excluded either. Your network seems to be pretty wide,” I replied.

“Maybe you are right, Apa. But I am not alone there. Lots of people have taken up this line of work,” he said with a faint smile playing across his lips.

He took a faded pen out of one corner of a showcase and started dusting it with a length of soft cloth. Such an old pen could only be displayed; no one would buy it. He raised the pen up and said, “This one has rusted away. There is no hope that anyone is going to buy it.”

“Why not?”

“This one is for writing love letters. No one really writes that stuff anymore.”

“Is that so?”

“Yes, indeed! Everything has become digital now. No one needs a painted blue envelope to slide their love letter in anymore.”

In my mind’s eye, I could see a blue envelope with a scented pink letter inside. The pen stall owner’s voice jolted me out of my thoughts. Inching much closer to me, he said, “Apa, do you know that someone has set up a machete stall here, at the bottom of this alley?”

“What do you mean by machete?”

“Sharp weapon. Which hacks people to death. Which silences them.”

“But why would somebody buy machetes in a book market?”

This time he whispered in my ear. “People buy what they need, Apa.”

On my way back home, I was lost in thought. I’d heard that essays written by some writers had sparked a great furor. One’s writing might hurt another’s religious belief. It was only natural. But why did people bother so much about what others believed? By the time I visited the pen stall owner a week later, several writers had brutally been murdered with machetes just because they wrote about their atheism. “Why? Why didn’t they write a suitable riposte instead?” I thought out loud. The man heard me and roared with laughter. “Who knows what world you live in, Apa! Murdering someone with a machete is way easier than writing a riposte.”

I did not say anything in reply and hurried back home. The man’s last comment had an effect on me. Although I could not explain why, I started shunning all social interactions and platitudes, and took to writing about issues of faith and atheism. I felt I’d written nothing unusual, but my pieces caused an uproar in certain circles. Some said I’d given the most fitting response to the execution-style murders of writers, while some others expressed their alarm at the threats I might face. But then there were those who, seething with anger, demanded my death. The waves of all these responses and rebuttals crashed around my home, too. My family members issued me an ultimatum, asking me to stop writing altogether. In a way, they boycotted me. I sat on the bed through the dark night. When I thought I could use some company, I pressed Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own against my chest. Why did she drown herself, having failed to bear with the world? Why didn’t she write more? Had the weight of her pen become so light that she chose to sever all worldly ties?

On some days, I ended up in front of the pen stall. When someone bought a pen from the left showcase, they appeared like an angelic child to me. As if the moment they picked up the pen, a yellow light glowed on their face, or maybe the sunlight just changed its hue.

Coming back home, I resumed writing as I was desperate to free myself of the pen. On the other hand, I was frightened to roam the streets, fearing attacks. Yet one afternoon, I was standing dejectedly in front of the pen stall. The owner came up to me and whispered, “Apa, do you remember I told you about a machete stall at the bottom of the alley?”

“I do. Why? What’s the matter?”

“One of those machetes has become stuck onto the palm of a man. He can’t do anything about it now—he’ll have to attack whoever he is asked to.”

“Really?”

“Yes! Please go back home and don’t return to this place anytime soon.”

“Why? You think I am scared? I’ll go wherever I want to. I’ll write whatever pours out of me,” I said firmly.

“The thing is, Apa, the decision in their circles has something identical to your resolve—they’ll slash at whoever they decide to,” said the man.

“How do you know about all this?”

“I get all the news, Apa. They have been on the lookout for you,” he said.

“What are you saying!”

Even before I could compose myself, I saw two men racing towards me, their eyes fixed on me. A machete was stuck on the hand of the man in front. Its sharp edge shone in the fading light of late afternoon. I was unnerved, bereft of all my senses. Was he as obligated to murder as I was to write? The pen stall owner’s scream shook me out of my shock. “Apa, run!” he said, gesturing towards an alley that had snaked through the cramped stalls. No sooner had I made a run for it than they reached the pen stall. The stall owner’s raised arm took the first blow. Before I could see blood gushing from his wound, I dashed towards the top of the alley and tried merging into the crowd. I had no idea when or where I left my handbag and orna. I was surrounded by hundreds of people who, it seemed, were enjoying a live show. Yet strangely enough, I felt that only two people existed in those moments—me and the man with a machete across his palm. As if I were in an empty field denuded of people. As if I were the game running for my life and he were the hunter closing in on me.

But I was mistaken. Soon, I realized that a young boy was running behind me. I was not sure whether he was trying to help me or the machete-carrying man. The boy caught up with me in a trice; he neither lagged behind nor outpaced me. Something magical happened as he touched my hand. Despite all the stress tormenting me, I could feel the weight of the pen easing up. Casting a sideways glance at him, I saw the veins on his hand turning green. I was reminded of the relay race that we used to play during our school sports competition. As if we were all players in a relay race. But life was too short for everyone to reach the target. If reaching the target was indeed important, why would it be a problem for one to build on another’s progress? While I was thinking along these lines, the boy suddenly vanished into one of the labyrinthine alleys. I’d have run after him if I were not being chased by a machete-wielding man. I looked over my shoulder to sneak a glance at my assailant—his eyes were exploding with hatred! Would he have spared me if I renounced my heretical ideas and expressed my allegiance to his faith? Would I feel alive if I did that? Thoughts popped into my head unceasingly and my whole life flashed before my eyes. People who had loved me and people who had rather disliked me—all those faces flashed through my mind, one by one, like one wave after another.

But neither the images nor the faces could flash by for too long. The second blow sliced right through my neck.

I have since kept standing in front of the pen stall.

About the Author

Afsana Begum is a Bangladeshi writer and translator. She has written novels, memoirs, and nonfiction essays. She has also translated quite a few books from English to Bangla. She has so far published twenty-one books, including three short story collections. Her debut story collection won the Gemcon Young Writer’s Award in 2013. She divides her time between Dhaka and Kuala Lumpur.

Afsana Begum is a Bangladeshi writer and translator. She has written novels, memoirs, and nonfiction essays. She has also translated quite a few books from English to Bangla. She has so far published twenty-one books, including three short story collections. Her debut story collection won the Gemcon Young Writer’s Award in 2013. She divides her time between Dhaka and Kuala Lumpur.

About the Translator

Rifat Munim is a bilingual writer, translator, editor, and columnist based in Dhaka. He was the former literary editor of Dhaka Tribune, a leading English daily in Bangladesh. He was a Jury Member for the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature 2019. His books include Bangladesh: A Literary Journey through 50 Short Stories (ed.). His essays and articles on different aspects of Bengali literature, as well as South Asian English writing, have appeared in World Literature Today, English PEN, Outlook India, Scroll, Dhaka Tribune, and The Daily Star.

Rifat Munim is a bilingual writer, translator, editor, and columnist based in Dhaka. He was the former literary editor of Dhaka Tribune, a leading English daily in Bangladesh. He was a Jury Member for the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature 2019. His books include Bangladesh: A Literary Journey through 50 Short Stories (ed.). His essays and articles on different aspects of Bengali literature, as well as South Asian English writing, have appeared in World Literature Today, English PEN, Outlook India, Scroll, Dhaka Tribune, and The Daily Star.

Prose

Excerpt from novel-in-progress Plastic Soul: On the Destructive Nature of Lava James Nulick

About the About Mary Burger

Ellipse, DC Denis Tricoche

Excerpt from My Women Yuliia Iliukha translated by Hanna Leliv

In the East John Gu

Fire Trances Iliana Vargas, translated by Lena Greenberg and Michelle Mirabella

Excerpt from Concentric Macroscope Kelly Krumrie

Autumn Juan José Saer, translated by Will Noah

Pen Afsana Begum, translated by Rifat Munim

The Game Warden Michael Loyd Gray

Current and Former Associates William M. McIntosh

Take Care Laura Zapico

Poetry

I am writing the dream Stella Vinitchi Radulescu, translated by Domnica Radulescu

and finally, life emerging

and the night begins

Letter to the Soil Skye Gilkerson

A Flight Adam Day

The World Ariana Den Bleyker

What We Held in Common Justin Vicari

The Shame of Loving Another Poet

How to Keep Going Rebecca Macijeski

How to Lose Your Fear of Death

How to Paint the Sky

Eternal Life Cletus Crow

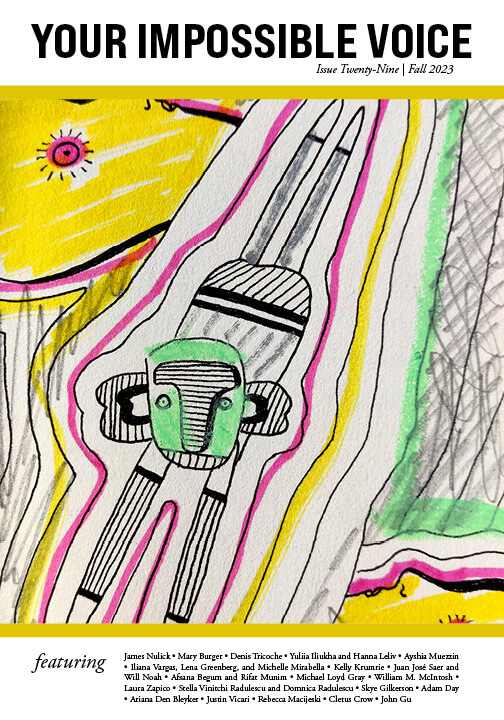

Cover Art

Deep Dive Ayshia Müezzin