Issue 29 | Fall 2023

Concentric Macroscope

Kelly Krumrie

The world becomes blurred; properties are no longer separate … in the manner of a vibration that always gives the same sound (but what sound?).

—Roland Barthes, “The Metaphor of the Eye”

Possibility: I do nothing.

Jenny walks out of the forest; there’s a clear ring of light behind her.

I admire her dedication and focus.

At the creek, I tell her that for a number of years, I was embedded with a group of nuns to document their language—or to co-create it.

They used instruments, shuffled their feet, sang out, spoke quietly to me.

I lost all sense of time.

Rather, I kept minutes, calendars, but time still slid out of my fingers, always at the corner of my eye.

Before I was recruited for the Cavern, as a linguistics student, I specialized in constructed languages, an eye for syntax, an eye that could undo anything—could rearrange, remake any sentence.

I loved minimalist painting: I spent much time in museums and galleries—grids and color fields, they revealed themselves to me, unfolded, fled open; I spent time with a man from a gallery, held cups of wine at events, viewed works from multiple distances, lay naked on the floor of the man’s apartment, clean, white—he stood over me, put on his glasses, slid his hand over his head, sighed, looked at me; I did all you could do like this.

I made a morphology of a grid of nuns’ making.

I fucked him until there was a color field of my own making in my mind’s eye.

Follow unfolding color until completion.

I showed him a color field, how to come this way.

A secret is that I let my languages unfold in this way.

Now, I’m waiting for something that will never come—a gap in the grid.

To remove myself from him, I had to put something between us—I agreed to descend into a half mile of earth and rock, no sound, darkness, everything off.

He’d expect me to puzzle over these numbers, would roll his eyes at my waiting, put his pencil roughly to my notebook.

What of him have I hidden in any language? Nothing, color field.

The next time I walk into the clearing, I feel frequency; I walk into different air, into the buzz of the pylons.

The message should be a question.

A question is how you get a response.

What do I want to know?

Me, here, in the clearing, after the Cavern, after the Gallery?

Listen: everything I think is wrong.

I shake my head, picture a root system fanning out.

I regret introducing him into this system.

I don’t need him.

Or the computer scientist, or the numbers—I throw the packet into the creek, the paper curls and sinks.

The day it is doesn’t matter.

Jenny’s signaling to an engineer and moving her right hand and arm in undulations, mimicking waves, pointing to the pylons, flexing her knees so her body rolls, explaining something to him, laying a fact flat.

He nods, also points; they’re miming what they want.

My notebook is not where I left it.

I coordinate locative shifts in my potential syntax.

That is, I look at it.

A crude hand in my notebook: pencil.

The computer scientist, when he’s working, emits a frequency.

His postpositional shifts at the table.

I suddenly feel variegated—streaked with worry—then it flushes out of me, in the clearing, when I see my work, my waiting.

I throw myself underground.

The computer scientist and I walk to the creek and linger by it; he puts his feet in the water and the action makes no sound.

I sit on a rock.

He tells me something I don’t want to hear, clear in the water.

He says I should reduce the situation to a location, explain my attraction to postpositions.

I can make them do whatever I want.

But where?

In the clearing.

I lower myself to the floor of the trailer.

The clearing in, the floor to, the trailer of.

Lifting the notebook, flipping through its pages, smudging the pencil, holding the paper up to the light, reveals nothing.

Why are you here. To create a message.

What’s the message. I don’t know.

Who are you sending it to. I can’t say.

Can’t or won’t. Can’t.

Incapable of looking up, I’m incapable of looking up—cavernous, small and hungry.

I went to the Cavern to perform a service, and I was paid, but it was also a form of opting out, electing to be underground, removing myself from any kind of surface, only service, to receive and give, then to receive payment so not selfless, not pure, but an exchange, a good one because I got more than money: I’m like this now, here, because of it, changed, emptier but still not yet ready.

It’s difficult for me to manifest a single moment, to draw it out long.

What’s the purpose of stretching it out if that’s not how I see it?

To vary my experience, back everything up with reason?

Nothing changes any moment.

The nuns huddled together like bees and whispered to one another, turning and whispering, all at once, passing messages along, whatever they took in; there was a room for this, a machinic sound, a forest of hydraulics, sliding metal—they didn’t believe they were talking to god, but that through this action god would speak through them, the quiet cacophony made something like static.

What were they saying?

It didn’t matter.

What mattered was what was cumulatively said.

And this was in a language none of them knew.

According to my notes, this action lasted days; they kept no track of it, felt it out, followed one another until it felt like the right time to open their eyes and close their mouths.

The room was dark and domed, at the end of a long, low-ceilinged corridor, all stone, trickling water, no light, a few candles at the edge of the room, hushed flicker, breath and water, they fasted, spoke through hunger, ate and drank what they heard and said.

I recorded this.

I wrote it all down.

They did other things, centuries-old experiments, exercises in tracing.

Archives traced, over and over, original texts hidden or lost, traced in various media: ink, paint, fingers in sand, a finger along another’s back and she would then trace her own finger, mirrored, dipped in paint, trace it onto paper or onto the wall, over someone else’s—what was on her back through her body then her hand then onto the wall—and at that point language would leave: whatever was originally written, thought, or said or heard then written, rewritten, traced, felt through a back, gone then—or not gone but remade, and this was what they wanted to see, how far they could take it, this farthest point, this was it, holy communication.

I recorded them in the kitchen, changing clothes, washing their hands, played the sound back, and they’d write it down somehow, rerecord it.

The echoes under there had to be god.

Jenny looks at me like she’s seeing something.

I’m only echo.

I can do this.

I’ll invent a valence—a frame for verbal arguments; for this new language I’ll stretch out all types of weather, a morphology of the clearing.

How many actors lever the verb, agency, static states, word particles that command these actions—all a description, an enaction, of this place here.

The numbers come to me in my sleep; they’re like nothing I’ve ever seen.

The computer scientists are restless; we’ve been here so long.

Nothing, nothing but walking.

Then an engineer with a clipboard reaches his hand out.

I keep walking, I don’t see it, then I see it, see it, see it—his hand, out, his eyes, his looking, his notes on my progress, which is nothing, his hand, something, my computer scientist, his waiting, my longing, we’re all waiting, clearing.

Verbs set the direction.

This is what the nuns refused.

That’s how their language will evolve: decades from now a syntactic elision, verbs gone first, what they’re heading to is copula, copular and choral, sound from mouth to ear, no interference, word on word, a lingual plain, a tongue along a knuckle.

A measurement is an assertion and a touch—to go from there to here, alone here, discretion, no information, all out of thin air.

Insert variable: irritant (the computer scientist).

Insert variable: company (Jenny).

Insert variable: framework (the pylons).

Insert variable: want (the engineer).

Insert variable: memory (the Cavern, copula, only sentence, any length of holding).

My eyes open in alarm.

I pick up a piece of chalk.

I put a pencil to my notebook.

I draw a grid.

I draw a series of lines, obtuse angles, curves and waves, vibrations, frequencies.

I draw concentric circles.

On the chalkboard I sketch one of the pylons—it looks like a person.

The framework’s lattice casts a shadow on the chalkboard and I trace it as the light changes, overlapping lattice moving down and across the board, and I step back and let my eyes settle into it, blur and focus, and the image lifts from the board, shimmers, settles back.

The computer scientist explains that he can make something random—easily—with a small set of inputs, from whatever notes I have so far, or the numbers, he can use them, it’s no problem.

Out the window, in the clearing, I see an engineer hand Jenny a packet of paper.

In the morning, I make coffee, stir cream into the cup with a small spoon.

A light knock on my door, the creak of the screen door, a light knock, knuckle on the frame, shadow through the window over the table, the shadow crosses over me, I look up, his face in the window, the engineer, the one with the clipboard, he jiggles the handle, I get up, I cross the room, I take the other side of the handle, I feel his holding the handle still, we turn it, the door clicks open, he hands me a note—written in rough pencil—asking me to have dinner with him in town.

Later, I go down to the creek, down to where a dam was, cubes of concrete and rebar, and I bend at my waist so that my ear is parallel with the water, I listen to it, the water in the rocks and grasses, along the mud bank, along itself and air, then I lean up angled, listen there, then stand again, and at each position the sound is different.

The wind tickles my ear, my hair, cracked branches, bird wing, heavy, heavy concrete.

Later, we walk down the road silently.

The bar is dim, lit by golden lamps, murmur of diners, clinking of utensils, we’re seated near the front window, across from one another, a candle on the table, and place settings, two filled glasses of water, and I drink from mine, my mouth dry from walking and saying nothing, and I set the glass down and wait, and he looks at me, the engineer, he looks at me and flushes red, picks up his glass of water and drinks from it, I pick up my glass of water and drink from it.

Under the noise of the bar, he says, My sister was in the Cavern, she told me what you did there, what you made for them; that’s how I found you—why I thought you’d be good for this.

This engineer works for the Agency then—we all do.

He had also read my dissertation on copular verbs and an old essay where I failed to tie copula to abstract expressionism, where I threw syntax at painting, grids, black paintings; this was on an old website I deleted before going to the Cavern: I cleared the record of myself.

He keeps talking.

He was a researcher at Duga, the massive over-the-horizon radar, an array of beams and cages constructed to broadcast shortwave radio bands.

He makes sweeping gestures with his hands, lattices his fingers to make the shape of it, then fans them out in a representation of transmission.

People called it the woodpecker because the transmissions sounded like tapping.

He makes the sound on the table, taps it with his index finger.

He jokes about leaking radiation, warns me not to touch him.

The waiter brings two bowls, though we never ordered, identical bowls of pureed soup, a vegetable I can’t identify, and for a while we eat in silence.

I have not uttered one word.

In the window’s reflection I see myself, him, the other diners, and through it, people outside in the square, and I recognize the back of a woman, her hair—from the Cavern?—walking away, stopping, looking toward the window, it’s Jenny, seeing me there with the engineer through the window, then a car drives past, when it’s past she’s no longer there, it’s nothing, or no one, maybe a lamppost, or a shadow, a pole, not Jenny, nor my reflection any longer.

We don’t pay; he winks at me.

Up the road to the clearing, he takes my elbow in his hand as if to guide me.

I’m tired of being led by men.

Until this moment, walking, at night, quarter moon, bright stars, quiet and cool, his hand on my elbow, until now, I hadn’t realized how lonely I’ve been, alone, with an unknown task, a zero thing to do, pulling nothingness from myself, at the Cavern too, I hear their voices, the nuns’, in the wind, his sister’s voice, one of them, it isolates itself in a quick burst of birdsong, and I’m still, empty, not able to say anything, I’m waiting, what I’m best at is waiting, but not for this, I’m tired of waiting, I know what I want now, so I take it.

I recognize this clearing.

I turn on the white noise machine.

I’m cleared, on, beneath the chalkboard, his shadowed form over me.

Color field—black.

Our voices static, the static behind the pylons’ alarm.

Can’t control this calling out.

After, I ask, What was at Duga? What did the tapping say?

He’s out of breath.

He says, I can’t say.

Can’t or won’t? Won’t.

Call out, tug down, pull off.

Color field—gray along the edges, a dusty white edging, then it unfolds black, black night in my open eye.

Jenny in water, her transmission.

The water’s made from my dissertation on copula, melting away, flowing through the broken dam.

I sit up, awake, alone, in the dark.

On the chalkboard, there’s a series of concentric circles; a note from the computer scientist slides under the door: a series of numbers, a line through them, an equation I could never recognize.

He told me once—the computer scientist—that an equal sign is an is.

Tongue along a knuckle, copula.

I’m hung up on the content of the message.

Hung up on an eye that could undo anything.

An I that can undo anything.

I draw a grid in chalk; it looks like a series of radio towers.

It looks like Duga.

About the Author

Kelly Krumrie is the author of Math Class (Calamari Archive, 2022). She lives and teaches in and around Denver. More information and work can be found at kellykrumrie.net.

Kelly Krumrie is the author of Math Class (Calamari Archive, 2022). She lives and teaches in and around Denver. More information and work can be found at kellykrumrie.net.

Prose

Excerpt from novel-in-progress Plastic Soul: On the Destructive Nature of Lava James Nulick

About the About Mary Burger

Ellipse, DC Denis Tricoche

Excerpt from My Women Yuliia Iliukha translated by Hanna Leliv

In the East John Gu

Fire Trances Iliana Vargas, translated by Lena Greenberg and Michelle Mirabella

Excerpt from Concentric Macroscope Kelly Krumrie

Autumn Juan José Saer, translated by Will Noah

Pen Afsana Begum, translated by Rifat Munim

The Game Warden Michael Loyd Gray

Current and Former Associates William M. McIntosh

Take Care Laura Zapico

Poetry

I am writing the dream Stella Vinitchi Radulescu, translated by Domnica Radulescu

and finally, life emerging

and the night begins

Letter to the Soil Skye Gilkerson

A Flight Adam Day

The World Ariana Den Bleyker

What We Held in Common Justin Vicari

The Shame of Loving Another Poet

How to Keep Going Rebecca Macijeski

How to Lose Your Fear of Death

How to Paint the Sky

Eternal Life Cletus Crow

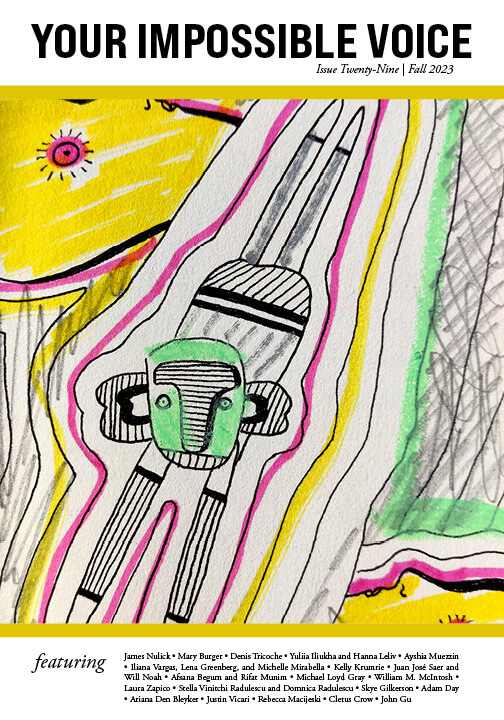

Cover Art

Deep Dive Ayshia Müezzin