Issue 25 | Fall 2021

Out There

Daryll Delgado

The alarm goes off at midnight, and she rises without resistance. She has to listen to a conversation, an interview, in a language that to her has always sounded like flames in a bonfire by the beach reaching into and repelling each other, or tiny embers dancing in the air to some tune carried by a gentle breeze, and other clichés picked up from listening to Bossa Nova Lite Radio and very limited, mediated exposure to what she does know is a complex, rich culture. She sits up in bed, reaches blindly for the headset on the table next to her and, without turning on the video function of her phone, puts herself on mute, and listens: The slow back and forth, the hesitation, the clipped answers in the beginning, the soothing voice of one and the soothed response of the other. Her eyes close, her mind drifts. She had spent three years learning the language. She should have been there herself, talking to people in the flesh, putting them at ease, making them bare their souls to her effortlessly. A skill she has always been complimented for. Instead, she has to sit here and try to catch as much of the interview, the actual words, not just the sounds, as best she can. She has to take notes, she has to listen. She pulls herself back to the task at hand. The tones shift, there is shy laughter now, teasing, which makes her smile, too. The two interlocutors’ tongues twist and linger over vowels, something she has been trying to learn, and she finds herself mimicking the woman whose slightly throaty voice now sounds more sure, more steady. The woman is trying to make light of things, the man is there with her. The woman is saying, All this, it’s just a fact of life for people like us, all the people like us all over the world right now, yes? Yes, indeed, the man tells her. No big deal. We are alive. We will survive. The woman sounds a tad defiant. The man does not press, keeps the woman talking. He is very good at this, she types on her phone. As she is writing the word appeasing a memory long suppressed suddenly surfaces unbidden, unasked for: A prolonged, lingering attraction acted upon on a whim one random weekend while on a break from fieldwork, a week of documenting gruesome murders of local peoples, and then finally a night at that beach on Camiguin Island. That old, forgotten life. The danger, the pleasure, the lack of guilt. The memory hits her like a forceful wave, so swift, so there all around her all of a sudden. Gestures, words, details surface like a relief as the background is chiseled away so effectively as to reveal the unmistakable scene. My god, what were we thinking? So clear to her now, others must surely have known, have seen it for what it was then. She feels her face redden and heat up in shame. She frantically readjusts her headset, breathes deeply, and tries again to listen. The line is still very clear, no static or ambient noise, images form freely in her head as she catches words, phrases, parts of sentences. The woman is talking about being grateful for the work and that the boss is one of them, He understands, he’s doing his best, he is a victim, too. The woman is describing her home now, there are seven other people living in it. Most days life is normal, no different from before. The woman is the only one who has been able to keep her job in the same fruit company. Oranges, mainly. As the man and woman speak, she is there with them, she sees it: the sun glaring unceasingly, the neat rows of orange trees, the organized orchards, acres upon acres of them. She smells the blossoms, the pulp, she almost forgets where she is: In her bedroom, in an apartment she has rented for a year now, behind a government hospital and a district police station, in Quezon City, GMT+8, thirteen hours away from where she should have been. The windows are shut tight to block out the sirens, the only noise she hears these days and nights. A week ago, she read in the news, an elderly man was found dead inside an apartment just a block away from the station. He was apparently stabbed multiple times in the middle of the night, but no one heard any commotion, any sound. Not the neighbors in the same building, not the police on duty in the station, not her certainly, even with the late work hours she keeps. She stops herself from imagining how, how it could have possibly happened, and pulls herself back to the conversation flowing smoothly in her ears instead. Right now, save for the conversation in her headset, it is as quiet and dark inside the room as it is outside, but something shiny has just soundlessly crossed the roof gutters. She slides down a little to have a look. She sees it now, the sliver of the night sky between the edge of her studio apartment’s roof and that of her neighbor’s, as long as she sits up halfway on her bed and stays at the right, though uncomfortable, angle. The light of the passing moon cuts through the curtain of blackness like a shock, a bolt of electricity. Next to her, her partner starts to snore, and she listens to this, too, to the regularity, the recently acquired familiarity of this noise that his breathing carries. It does not so much impede as much as it adds another texture to the voices and the silences around her. She closes her eyes, a cloud has shifted, and she feels the light, she is now inside it. She grips her sleeping partner’s arm. In gratitude, in remorse. It has only been a year of living together, but still … We are alive, we will survive. The shameful lapse of judgment—that night at the beach, brushing against someone else’s damp skin—is once more swept away for the time being. Her partner stops snoring momentarily, stops breathing as though to listen to what she has to say, and then he resumes, first a soft whistle riding on the breath, and soon full-throated snoring in earnest, neither too loud nor unpleasant. She sighs, caresses his chest, she listens. The conversation between the man and the woman is still going smoothly. In the morning, a concise report will be written: The interview went very well, remote assessments are effective, hold all my travels for now, in-person meetings not necessary. She can leave the call already, go back to sleep. But everything in her and about her is now on high alert. She could go for a walk. She checks the time, the curfew is on for a few more hours, so she cannot leave the house. Maybe she should open the windows, listen, really listen to everything that goes on during these late hours. The moon is still out, no one needing the cover of night could possibly get away. Maybe she will catch someone in action, if she just looks and listens very closely. Maybe she should wake her partner up, talk to him, confess, admit, commit. The conversation in her headset continues, she realizes that she has not turned it off and the man and woman are now talking about something she feels she should not be listening to. Their combined voices tread flirtatiously over the Babel of grief, uncertainty, resignation of many homes in distant locked-down cities. The lush tones, the swirl of tongues over certain consonants, the melodic call and response, the one-on-one of two no-longer strangers, soar past the arcs of sunsets and moonrises she imagines are probably passing a million bedroom windows at this very moment, and their light reaching deep, deep, deep into her. The memory of the indiscretion, the entirety of an old buried life and the old beliefs attached to it is distended and dislodged, floats back to the surface, and she lets it. She leaves it there and stares at it as she listens.

About the Author

Daryll Delgado is the author of the novel Remains (Ateneo de Naga University Press, 2019), and the collection After the Body Displaces Water (USTPH, 2012), which won the Philippine National Book Award for best book of short fiction (2013) and was a finalist in the Madrigal-Gonzales First Book Award. She is currently at work on a third book, excerpts from which have come out in Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, The Near and the Far , Vol. 2 ( Scribe Publications, 2019), and Likhaan Journal (V. 14, 2021) She co-edited Lunop, a collection of poetry, narratives, and images about Typhoon Haiyan (Leyte-Samar Heritage Center, 2015); and Ulirát: Best Contemporary Stories in Translation from the Philippines (Gaudy Boy, March 2021). She has taught in the University of the Philippines, Ateneo De Manila University, and Miriam College. She works for an international NGO, where she heads the research and stakeholder engagement programs for Southeast Asia and writes global reports on migration and labor issues. She was born and raised in Tacloban City, and maintains a residence with her husband and pro bono editor and lawyer, William, in Quezon City, Philippines.

Daryll Delgado is the author of the novel Remains (Ateneo de Naga University Press, 2019), and the collection After the Body Displaces Water (USTPH, 2012), which won the Philippine National Book Award for best book of short fiction (2013) and was a finalist in the Madrigal-Gonzales First Book Award. She is currently at work on a third book, excerpts from which have come out in Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, The Near and the Far , Vol. 2 ( Scribe Publications, 2019), and Likhaan Journal (V. 14, 2021) She co-edited Lunop, a collection of poetry, narratives, and images about Typhoon Haiyan (Leyte-Samar Heritage Center, 2015); and Ulirát: Best Contemporary Stories in Translation from the Philippines (Gaudy Boy, March 2021). She has taught in the University of the Philippines, Ateneo De Manila University, and Miriam College. She works for an international NGO, where she heads the research and stakeholder engagement programs for Southeast Asia and writes global reports on migration and labor issues. She was born and raised in Tacloban City, and maintains a residence with her husband and pro bono editor and lawyer, William, in Quezon City, Philippines.

Prose

Bomarzo Cecilia Pavón, translated by Jacob Steinberg

Sister in Basement, Manny Again Elsewhere Robert Lopez

Visitations Caroline Fernelius

Solution Linda Morales Caballero, translated by Marko Miletich, PhD

Auditions for Interference Theory Emilee Prado

Life Stories Robert(a) Ruisza Marshall

Out There Daryll Delgado

The Embassy Khalil AbuSharekh

Shaky From Malnutrition Mercury-Marvin Sunderland

Weatherman Gillian Parrish

The Taco Robbers From Last Week Steve Bargdill

Poetry

Epigenetics Diti Ronen, translated by Joanna Chen

i once was a witch Kiik Araki-Kawaguchi

Thralls Kevin McIlvoy

Mine Brian Henry

Catastrophic

marble chunk Shin Yu Pai

shelf life

Rebirth Tamiko Dooley

Before the Jazz Ends Adhimas Prasetyo, translated by Liswindio Apendicaesar

After Jazz Ends

Scent of Wood

Cover Art

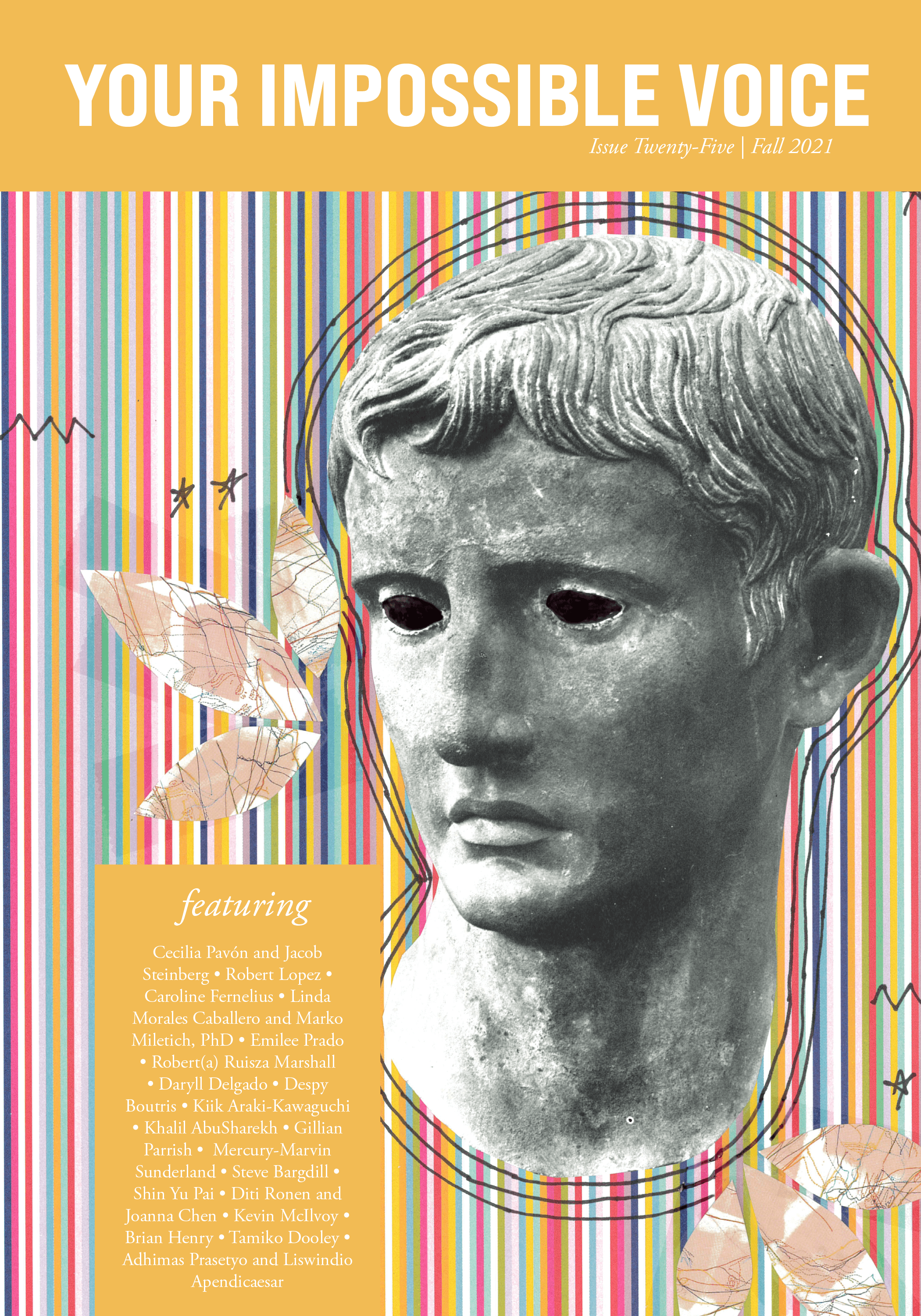

Untitled Despy Boutris