Issue 25 | Fall 2021

The Taco Robbers From Last Week

Steve Bargdill

Dean didn’t think he’d ever again feel comfortable at Taco Bell, but he agreed to Tacos El Chimpa’s because No Están Buenos … ¡Pero quitan el hambre! had been spray-painted underneath the sign. Dean knew enough Spanish to know that meant bad tacos. If we’re going to eat tacos, he said, they should at least be terrible. The waiter placed glasses of jetsam-flaked water in front of the boys. The water rose out of the glasses to the yellow-stained ceiling, formed little gray clouds bumping against each other, and sent tiny shocks of lightning, making everyone’s hair on their arms stand on end.

This is ridiculous, said Will. Don’t you have bottled water?

Jarritos. We have all the flavors. The waiter Vanna-Whited an aluminum cart on wheels, the sides splattered with dried hot sauces. Help yourself to our salsa bar.

The boys watched through the window the drooping maples and ash trees, the branches burning autumn torches. The burritos and tacos and refried beans arrived in parchment-lined plastic baskets with sporks and dried-out lime wedges. The tacos had the consistency of wet dog food. They ate trying not to taste.

This is the place we should have robbed, said Dean.

Last week, hands on their knees squatting outside the Taco Bell, Dean and Will had scrutinized a quarter that had landed perfectly balanced on edge beside a dandelion. The dandelion had crawled from a crack in the blacktop. Heads, they’d rob the Taco Bell. Tails, they’d pay. Will told Dean that he’d just purchased a brand-new Windows three-point-eleven computer and a stereo with dual cassette player and subwoofers. I can kinda play solitaire on the computer, Will said.

Dean wasn’t exactly sure if Will could even work the subwoofers, but the computer and stereo were for Will’s new apartment in Columbus.

I want a bacon-cheeseburger burrito, a couple tacos, Will demanded, and a Mountain Dew.

All Dean had at home was Big K Mountain Lightning, which wasn’t real Mountain Dew, which was only a shadow of Mountain Dew, which when poured into the Styrofoam cups stored in Deans’ garage dissolved the cups from the bottom up.

I just paid the deposit and first month’s rent, Will said. I’m broke.

For Dean, the issue was always the electric bill. The quarter landing on its edge severely complicated lunch. If the boys had looked, they would have seen heaven glinting from the dandelion’s crack.

Dean slap-dashed a plastic gun between his hands.

We need a decision, Will said. In the right light, Will looked like he had no beard, or in the wrong light, he looked like he had an abundance of peach fuzz. They smelled burning taco meat. The ski mask Dean pulled over his face was big for his head. Will pulled on his ski mask too, and they waved the plastic guns. The cashier tried to give them money, but they refused. All they wanted were tacos, and a fucking bacon-cheeseburger burrito, Will screamed.

And Mountain Dew. Two Mountain Dews, Dean yelled because he didn’t like the Big K Mountain Lightning any more than Will.

Sweat poured over Dean’s eyes underneath the oversized ski mask, which he tore off. The cashier bagged their food. Dean and Will ran for the door. The manager burst from his office. Dean pushed him aside. Will dropped the food. Mountain Dew soaked the manager’s shirt. The boys drove away as fast as the in-town speed limit allowed. Will went back to the Taco Bell because he hadn’t taken off his mask and no one at the Taco Bell knew what he looked like. He purchased twelve tacos for nine dollars and forty-eight cents and no Mountain Dew because all he had was a ten. They ate in Dean’s garage and drank the Mountain Lightning as fast as they could before the cups melted. Robbing their hometown Taco Bell seemed to Dean to be their last great adventure.

When the boys finished their lunch at El Chimpa’s, they stood in the parking lot, leaning against Dean’s Ford Ranger. Dean shoved his hands into his Wranglers. He never wanted the truck, but now felt the truck spoke volumes about who he was. A thin rust-line ran above the right back rim. Will’s mattress and bed frame lay in the back of the truck. The bed was the last thing to go up into Will’s new apartment. Dean wondered if the rust would disappear if he rubbed at it with a soft toothbrush. He fumbled for a Marlboro. He lit the Marlboro and choked on the first puff. He was a brand-new smoker and had only been at the habit a few days. He thought smoking became him and maybe made him more like his father.

We could have gone to a Taco Bell, said Will.

They have cameras in those Taco Bells, Dean said, and they’re linked. They see into each other’s stores and what happens in one affects what happens in another. They probably have our posters in the back offices. We could get caught.

Columbus was dirty with cigarette butts and candy wrappers, and flyers stapled to telephone poles seeking missing cats or wanting yard work done. Advertisements for college painters and open mic nights. Election campaign posters stuck in front of businesses sporting Bill Clinton headshots and slogans: For People, for Change. Newport Concert Hall hustled thick lines. Street Scene Bar slathered gravy over wide pieces of meatloaf and red skins still in the mashed potatoes while tour guides nursed beers and told ghost stories about prohibition and the voices sometimes heard echoing through the abandoned downtown prison. Law students lost wallets at chess with the homeless at Insomnia Coffee while the lower class homeless spouted bad poetry at the corner UDF and smoked Basics. On Chittenden, with its mauve brick apartments, girls in bikinis soaking in kiddie pools, fraternities hiding in slums. Fornicating in the middle of the topiary O of Ohio State’s front lawn, then stripping naked, throwing clothes to the pavement, walking the double yellow line of High Street, and the goldfish pond at Ohio State was a dark, deep mirror. The fish grabbed at breadcrumbs, their little mouths popping open, making bubbles like they were out of breath. Sometimes, when you looked into the pond, the end of your life reflected back at you in the shape of a flickering candle. There was always something going on in the city, unlike Dean’s hometown with only the one Taco Bell and all the almost-harvested corn at the edges.

When they got the mattress through the sharp turns of the narrow stairs that smelled of ashtray and mildew and into Will’s bedroom, they lurched the mattress onto the floor and collapsed onto it, arms crossed at their heads for pillows, staring at the popcorn ceiling.

You should move in.

Dean thought about his job at Big Bear Grocery, and he thought about the moms whose groceries he bagged. Lipton soup mixes, boxes of Hamburger Helper, pounds and pounds of ground beef, bacon, cheap kielbasa, frozen green beans, and frozen peas. He followed the women to their cars, chatting about their toddlers and pre-teens, their kids in their last year of high school, unsure of how they were going to pay for their kids’ upcoming soccer club fees or college expenses. He feigned interest and thought about his electric bill, which was always a worry ever since Dean had turned sixteen. Working forty hours over the weekend, school during the week, a cell phone bill—the cheapest vehicle he could find to drive himself back and forth from school and the grocery store. And Dean didn’t know the difference between an alternator and an injection pump; he didn’t know where the oil went; he was pretty sure he thought he knew how to fill the windshield wiper fluid. All these mothers taking care of their own families, and he let them fondle his hair for two-dollar tips to pay the bills. His father had split before all the shit, and Mom held on as long as she could. Then the ventilator moved in and brought friends: the wheelchair, the lift, the commode chair, the shower chair; the hospital bed, the feeding pump, replacement tubes, tracheostomy dressings, syringes for cuff deflation and inflation, gloves, the portable suction machine, tubing, catheters, supplemental oxygen tanks, a heated humidifier, and they hung around the kitchen table playing cards—Euchre, pinochle, canasta. Dean never understood the rules to the card games, no matter how many times his mother explained. The lights, the air conditioner, and the heat were all turned off to keep costs down, to keep the ventilator breathing, its glowing orange eyes from the dark corner of the living room always staring wickedly, unblinkingly at Dean, who waited, exhausted, in the threadbare armchair for something to happen. At least the Ford kept breaking down at the most opportune times. Once, the truck told Dean it was out of gas two blocks after he filled the tank. Dean opened the hood and a fifty-dollar bill wind-flitting smacked him in the face.

On the way home from the mattress trip, probably the last time he’d ever see Will again, not even out of the city, but seven or eight blocks from Will’s apartment on Hudson and Indianola, he wished maybe they had kissed, had said at least a better goodbye, but they didn’t, and it didn’t make sense because he had only dated girls all through high school, and girls were perfectly fine to date, there was nothing wrong with them at all, because they had nice curves, and a slither of smoke that smelled of thin-sliced onion peelings over-roasting in an oven seeped from the Ranger’s heater vents. He found a spot to park on fatigue-worn crocodile-spackled asphalt behind a two-story brick building with wild columbine twisting around the gutter spout and knotweed making a home in the mortar. Small rectangular awning windows lined the second story, a few open, most closed, caked in a heavy amount of dirt, the glass turning blue with the sun’s age.

Dean flipped his phone open. He didn’t want to call Will but couldn’t think of anyone else to call either, and then his phone battery was dead. This was the cell phone Will made fun of him for having. Are you a drug dealer, Will had asked. But Dean bought the phone at Radio Shack because if something happened to his mother, the doctors would be able to reach him.

He walked around to the front of the building and discovered a coffee shop. A chill in the air, and everything smelled like fire and dull mist, withered edges of a ripe earth. The shop’s floor was dingy laminate tiles. A folk singer banged on a guitar, wearing a tank top and no bra, armpits sprouting thick hair next to a planted fern growing wild. Women with short hair and flannel shirts crowded the tables and along the wall. In general, the majority of the coffee shop’s clientele were women. Dean asked what the rainbow sticker on the cash register meant because he didn’t know, and the rainbow seemed misplaced in comparison to the rest of the coffee shop with the high-end macchiatos, which he didn’t know what macchiatos were either, and asked because back home with the corn and the one Taco Bell, there was gas-station black with optional powdered creamer and packaged Twinkies and Ho Hos, so the cappuccinos, iced green tea lattes, tiramisus, cannoli, and zeppole, the grunge pen and ink artwork on the walls, everything was new and exciting. He ordered a caramel coffee. He’d never had caramel in his coffee before.

Nowhere to sit, he ambled to the sidewalk table underneath the awning where a woman sat with sharp eyebrows. A breeze played with her hair, which she had tied off in the back, but fell around her ears in long single strands reaching down past her neck and half-hid her eyes. A random dandelion parachute seed floated into one of the hanging flowerpots. The seedling sprouted, shot out broad leaves, a thin milky stalk stretching toward the sky. A bud opening petals one by one until the petals dried into the rustic oracle, the fluff globe of seeds, dead and tossed away into the world, and then gone and shriveled as if the weed never came in the first place. The woman deep sighed, drank her coffee, and when her coffee was gone, she raised her arms high, bringing down the clouds into the shelter of the awning with her fingertips, the afternoon sun bright and hot for a late September day. The metal table they sat at shivered with oxidized patches. She pinched her bottom lip between her thumb and index finger. Her eyes were like clear night—dark, deep, mysterious, beautiful, unable to be understood. She reminded him of his mother when she was younger and vibrant and before the ventilator. She grabbed napkin and pen and wrote down a phone number and handed the napkin to Dean. I know an auto mechanic, she said. It was the same phone number black-Sharpied on the homemade sign advertising an upstairs one-bedroom apartment for rent.

“The house was always being an ass, changing out the wallpaper to remind him of all he wanted to forget.”

Four and a half weeks later, Will drove from Columbus to see Dean. But because the shag carpeting needed mowing again, and because Dean was afraid what the house would do, and afraid Will would stand over his mother and whisper Jesus exactly like he had the last time, the boys sat in the garage drinking Big K Mountain Lightning. They picked up stones and threw the stones to the end of the driveway. They walked the short street and kicked at empty soda cans and then they returned back to the garage and drank more Big K. Dean couldn’t figure out why Will was even there. They decided to cruise the Main Street six-block strip, zooming repeatedly the abandoned bloated movie theater slowly drowning brick by brick into the river, the bank and the lawyer’s office, the myriad of hollowed-out buildings, their blank windows revealing empty, dark interiors, and the bars blinking neon pink open signs, old men stumbling out the doors, booze on their breath, skanky women too fat and too many tattoos or too skinny and too much lipstick—the river’s mildew stench wafting over the bridge. Dean and Will didn’t get many passes through Main Street when the Ranger stalled out. They remembered the theater when they were kids, when popcorn was heavy in the air, Cow Tales and Boston Baked Beans in their hands, big marquee lights against the night. They pushed the truck to the curb and walked. They found the railroad and followed the tracks cutting through trees and fields. The low train-whistle signaled. They watched the freight train. The boxcars, and the wind coming off the tankers, and the flatbeds loaded down with shipping containers, the countless unreadable graffiti tags. There’s got to be something to do around here, said Will. Always something to do in Columbus. Even if you’re broke. Are you broke, Dean asked. No. A long silence hung in the balance of the train’s rhythm that moved through the earth, felt in depths of bone and chest; the train was a great beast of smoke and metal and glass; a thing determined to move forward and feed off speed, hard rails, and sweat. Dean lit a Marlboro with a match. The fire flared against his shirt and face. For a flash moment, Dean was the only thing visible in the night. He allowed the match to burn to his thumb. He cussed and sucked on his thumb between puffs.

Saw an old cemetery back there a bit, said Dean.

The cemetery was littered with broken stones and grass going to seed. The boys cast a shadow over a stone split in two and uprooted.

I’ve always wanted a headstone, said Will.

For what, Dean asked.

Coffee table? Maybe two coffee tables, since it’s split like that. One for each end of the couch. How awesome would it be to hit the Taco Bells in Columbus? Kick back on the couch with a couple tacos and drink Mountain Dew. We could have coasters to keep condensation off our coffee tables. The gravestone from the late eighteen-hundreds, a child, not more than a year old, all moss and dampness, a bit of quartz embedded in the slate, a sunburst design at the top with eyes gazing out over the horizon, dandelions crawling all over the edges—No Taco Bell, Dean said. We could do Chinese take-out. They probably sell Mountain Dew. Dean reached for another cigarette. He succeeded in not coughing on the smoke and was proud of that. He scratched his chin and stretched out his neck. Considered, for a moment, growing a beard like Will.

Will began the walk back to the train tracks, back to where they had left the Ford Ranger on Main Street.

Wait, said Dean. Why not take the gravestone? It’s just lying there. No one’s around. No cameras. Nobody’s watching. Why can’t you have a gravestone for a coffee table? Will grinned. I’ll get the truck, Dean said, and he walked alongside the empty railroad tracks back into town. He realized how near they had pushed the truck to the high school. When his mother had gone to school, they’d installed security glass because a student tried jumping from a third-floor bathroom window. Dean’s own freshman year, one of his classmates was raped by the football quarterback, who was a senior; this happened on the first floor in the girls’ locker room, where there was a window, and she couldn’t escape either. In Dean’s American history class, the teacher with chalk dust covering his fingers announced that Dean would never leave, and that he was exactly like Simon Stimson, that he would hang himself in some attic, or at least would have some other pointless and meaningless death. Dean wasn’t sure he knew who Simon Stimson was. Maybe Simon was the organist for the church, but he couldn’t be sure because by the time he was fifteen it had already been such forever since sitting in a pew listening to any kind of sermon. And even longer since he’d held faith in anything, since probably just after his father took up drinking as a contact sport with inanimate objects and just before his father split, leaving him alone with his mother, who wouldn’t, or couldn’t, or absolute refused to die. Dean imagined he could create whole thunderstorms like what happened at Tacos El Chimpa’s with the glasses of water, and that would at least be something he could control. He got into the Ford Ranger and turned the key and nothing happened. The napkin with the phone number slipped from the sun visor and fell into his lap. He called because the woman said she knew an auto mechanic and he was tired of his truck throwing these little fits, and it was probably around 2 a.m. and he’d only get the answering machine of a garage and didn’t expect the woman to answer, Hello? Who is this? Her voice sounded disembodied and brittle. Dean, it’s Dean, Dean said.

The truck started. He flipped the phone shut. He shifted into first gear and took off down the street toward the long way around to the cemetery on an old potholed road. Will grinned like he had gotten laid, and they loaded the stone’s two halves into the truck. A cloud spat cold heavy rain. Let’s get the hell out of here, said Will. The boys scrambled into the truck. The windshield wipers decided not to work, and the radio tuned to unforgettable 1220 WERT and the Dr. Demento Show. Dean wondered if the night’s rain would make the rust worse. He thought about spray paint to cover the rust, or a trip to an auto parts store in the morning for rust treatment in a can. If he could only fix his truck, then he would be okay.

When Dean returned home, the living room television, volume on low, droned Blue Blocker infomercials. The ventilator sucked in the air and beat in and out. The wallpaper, still left over from the 1970s, crawled with horse images and carriages, old men with canes, women with wide-brimmed hats. The house asked Dean if he recalled the horse-print shirts his father used to wear, and the house was always being an ass, changing out the wallpaper to remind him of all he wanted to forget.

His mother’s eyes were closed. Heaving tentacle tubes full of breath slithered all over her body while she snored. The room smelled of urine. The ventilator cord ran to the wall outlet. He would wake her if he turned off the television. He collapsed into the armchair and waited.

Dean remembered sitting on her lap watching Mr. Rogers and Captain Kangaroo. He remembered the hot summers his mother put in the window ACs, and Dean dressed in long johns, got down on all fours, and buried his head into the carpet pretending the shag was snow, pretending he was a snowblower, watching the build of static between the house and his head. He remembered too his first day of kindergarten, holding on to her hand as they walked a long hallway stair painted with a green snake swallowing an old lady. The kindergarten room had soft carpet and easy lights and another stuffed snake running alongside the alphabet border at the ceiling. Kids he didn’t know. Where he met Will. And Ray Fay, whose name rhymed with gay and he and Will and all the other little kids chanted over and over Gay Ray Fay has a rubber butt and every time he farts it goes putt putt putt Gay Ray Fay’s rubber butt, and he remembered asking his mother why Ray was always crying, even though at six years old he already sorta knew.

But mostly, Dean remembered holding his mother’s hand, and how she had told him everything would be all right if he was kind.

His mother looked like a small child in the bed, the ventilator helping her breathe. Dean went around the house and turned on the stereo, the oven in the kitchen, all the lights, the window air conditioners, the microwave, the dishwasher. Anything that ran on electricity he turned on, hoping to blow a fuse, and he sat back down into the threadbare armchair and waited. “You are an asshole, a bonafide loser,” the house told Dean. Then the house told Dean he had to go to work in the morning, and one day he’d wake and discover the ceiling caved in beside his bed. Dean knew, if the house wanted to, the house could kill him. Dean got off the chair and turned everything back off, except the living room television, which was discussing the benefits of ShamWow, and the ventilator refused to look at him. His mother looked dandelion yellow, like something that had rumbled through life, something that could not be translated or explained.

Dean descended into the basement among the cobwebs, the dank, and the mildew, the insulation falling out of the ceiling. The water heater and the furnace hid from him. He found the workbench under a single bare lightbulb where the handsaw and an assortment of screwdrivers and Allen wrenches collected. Then the boxed Christmas tree, the washer and dryer. Utility electrical extension cords, broken patio furniture, bicycles, an old garden hose with holes. Recycled glass jars holding nuts and bolts and screws and nails. Wall outlets. But he could not find the circuit breaker. The house was hiding the circuit breaker and maybe hid the circuit breaker in the upstairs attic, where he found shoes and empty hangars, winter blankets packed in mothballs. Shoeboxes filled with photographs, stale cigarettes, an ashtray collection, replacement lightbulbs still in cardboard packaging. And the old framed Polaroid of his bearded father, cigarette hanging from his bottom lip, a glass bottle of Mountain Dew in his spare hand, pushing Dean on a flimsy backyard swing while his mother in the background laughed away in a mauve summer dress.

Now she lay in a hospital bed in the living room tethered to machines, and he, in turn, was tethered to the machines to ensure their continued easy running. Dean held the ventilator’s power cord in his hand. The house said, Don’t do it, don’t do it. But he could yank on the wire and he’d be alone in the house with the overgrown shag carpeting.

Dean dropped the wire.

The house, the ventilator both sighed.

Dean placed his hands upon his mother’s face on either side of the tubing that covered her nose and mouth. She felt like cold autumn, like a dead leaf separated from the tree. She wheezed, the air forced in and out of her lungs. She spoke through the tubing, and he couldn’t make her words out, but he thought she said, It’s okay, or maybe she said, Do it, unplug me. The ventilator pushed extra loudly, so it was hard to know really, and Dean didn’t want to pull the plug, or at least he didn’t want to be in the same room when he turned off the power and would have to watch her take her last breaths. His hands moved from her face to her hands, and her fingers were limp. Her hair was held back and white, unlike the brown silk of her youth, the sandals she used to slip her feet in and out of. He took the cord up and yanked. The house grabbed too through the outlet and refused to let go, a tug of war until Dean braced his feet against the wall and pulled until the plug came out and the ventilator shut off.

In the morning, Dean, droopy-eyed, wanted a cappuccino, but that was two hours away. Instead, he fumbled for one of the stale Lucky Strikes left over from the attic shoebox, and he lit that up, and it smelled like burned cherries and burned his throat raw. He stumbled down the stairs and plugged the ventilator’s cord back in the wall. The ventilator woke up, glared at Dean with the orange eyes and forced the oxygen into dead lungs.

Someone banging on the door, and Will stood there with a lopsided grin. You can’t go to work, Dean. Your truck’s not running.

How do you know?

I found legs. I tried to steal it to haul the legs away.

It does that sometimes when it doesn’t want to go. Dean got into the Ranger and she started right away. Will hopped into the cab. Dean drove to Big Bear. I have to work. Can you get the legs yourself?

Sure, Will said.

Dean’s manager told him a drinking story that happened over the weekend in a field of corn that involved the attempted tipping over of a cow, and he thought it was the most hilarious thing ever, and when he asked what Dean did over the weekend, Dean straight-faced said, “Ate some tacos. Stole a gravestone.”

When he returned home, Will spotted a cop at Dean’s front door. I’m not stopping, said Will, and pushed Dean out of the truck. The cop resembled the Taco Bell manager—overweight and bad, nonthreatening gun and bad. The cop followed Dean into the house. The house sighed. The ventilator droned, but Dean was alone in the house, standing above his mother, the cop by his side. Dean collapsed into the armchair.

“I think she’s dead,” the cop said. He radioed the EMS. The ambulance arrived, a few more police, photos taken.

“This is bad timing, Dean,” the cop said. “You stole a gravestone.”

“I can tell you where it’s at, I guess.”

“You don’t have it?”

“They stole my truck.”

Later, Will called. “They got our coffee table. No arrest or anything. They just took it. Like we never had it in the first place.”

After the funeral, after the grave digging, where the backhoe made the earth thin, after they covered the casket with dirt and set the headstone in the ground, Dean called a realtor. The house didn’t much care, except it flipped Dean off as he packed his belongings into his truck. The napkin with the phone number for the auto mechanic, for the second-story one-bedroom apartment fell from the truck’s sun visor into his lap. And before he left, he went into the living room, where there was no longer anything, where everything was empty and wanting, except for the still overgrown shag, which he buried his head into and watched the sparks fly between his head and the house.

About the Author

Steve Bargdill is an emerging author with publications at Literary Orphans and Tinge Magazine. He’s the recipient of the 2019 Dick Shea Memorial Award for Fiction, and holds a master of arts from the University of Wyoming and an MFA from the University of New Hampshire. He currently teaches creative writing at Great Bay Community College.

Steve Bargdill is an emerging author with publications at Literary Orphans and Tinge Magazine. He’s the recipient of the 2019 Dick Shea Memorial Award for Fiction, and holds a master of arts from the University of Wyoming and an MFA from the University of New Hampshire. He currently teaches creative writing at Great Bay Community College.

Prose

Bomarzo Cecilia Pavón, translated by Jacob Steinberg

Sister in Basement, Manny Again Elsewhere Robert Lopez

Visitations Caroline Fernelius

Solution Linda Morales Caballero, translated by Marko Miletich, PhD

Auditions for Interference Theory Emilee Prado

Life Stories Robert(a) Ruisza Marshall

Out There Daryll Delgado

The Embassy Khalil AbuSharekh

Shaky From Malnutrition Mercury-Marvin Sunderland

Weatherman Gillian Parrish

The Taco Robbers From Last Week Steve Bargdill

Poetry

Epigenetics Diti Ronen, translated by Joanna Chen

i once was a witch Kiik Araki-Kawaguchi

Thralls Kevin McIlvoy

Mine Brian Henry

Catastrophic

marble chunk Shin Yu Pai

shelf life

Rebirth Tamiko Dooley

Before the Jazz Ends Adhimas Prasetyo, translated by Liswindio Apendicaesar

After Jazz Ends

Scent of Wood

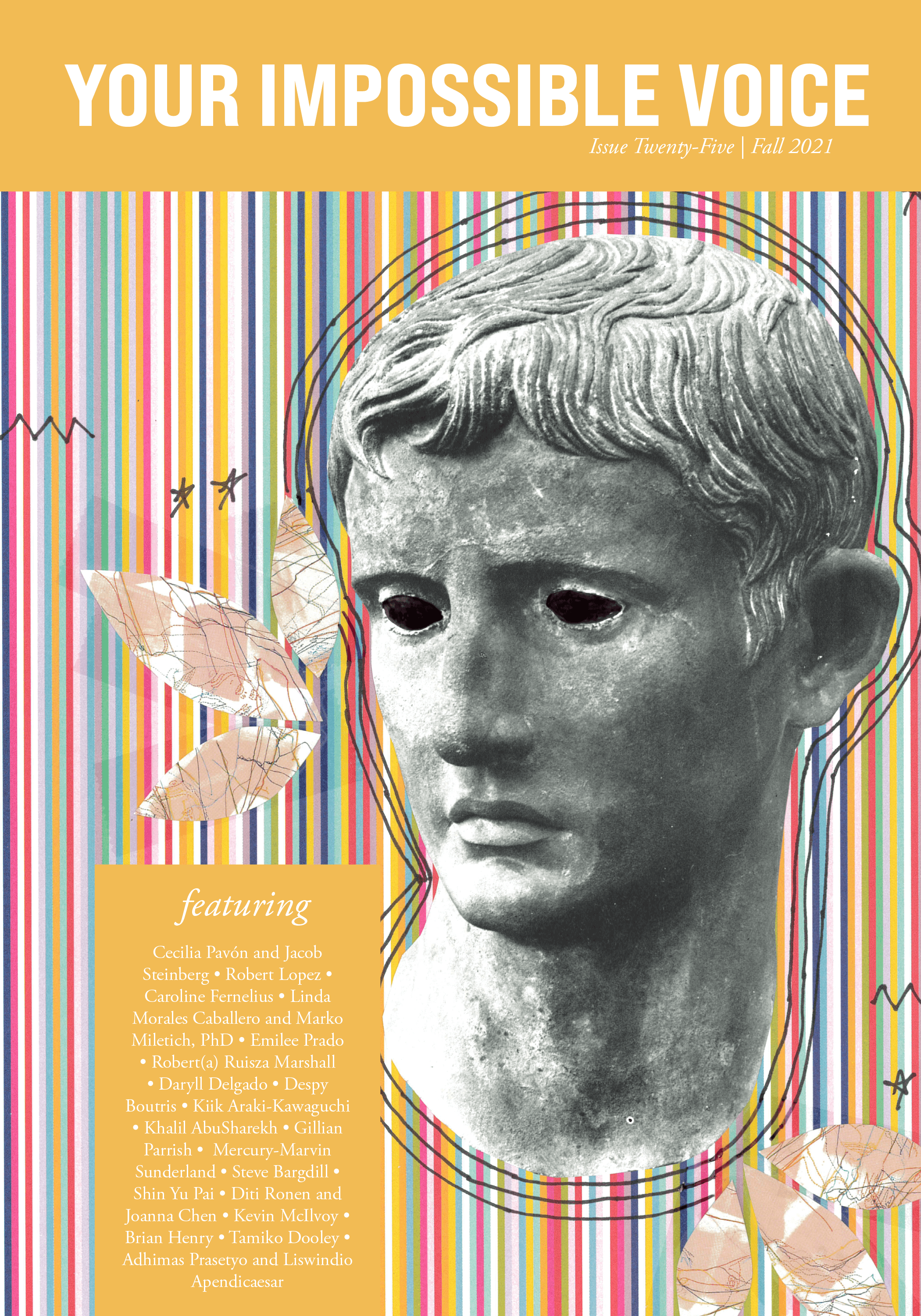

Cover Art

Untitled Despy Boutris