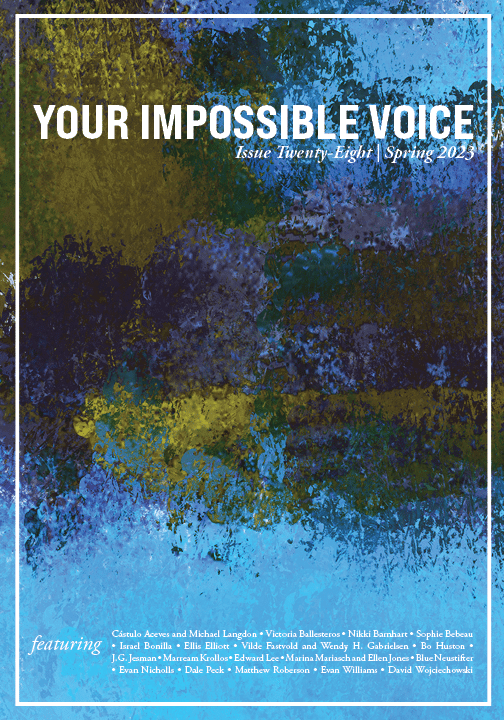

Issue 28 | Spring 2023

Torch Song of Myself

Dale Peck

The first man I was sexually attracted to was Luke Skywalker. The first man I loved shot one of his johns when he was fifteen. The first man I had sex with was my best friend in college. The first man I dated used to break into the chem lab at SUNY Purchase to sleep on one of the slate tables. The first man I thought I was going to spend the rest of my life with was already spending the rest of his life with another man.

Lamoine first. He lived around the corner when I was twelve—although in Kansas “around the corner” meant a mile by (dirt) road, maybe half that as the crow flies. Luke was a galaxy away, on an icy planet in the Hoth system. May 1980: remember how Han Solo gutted the tauntaun and pushed Luke inside the carcass to keep him from freezing to death? (Q: What’s the internal temperature of a tauntaun? A: Lukewarm!) Mackie was my best friend in college, but I wasn’t his. That role went to a boy named Mark, who almost beat Mackie to the punch—who, at any rate, stumbled drunkenly into my dorm room one night and said, “Do you want to fuck?” What a pussy I was! I didn’t say no, I said, “I can’t,” and two and a half years later, when I saw Pierre for the first time, I was still equivocating. March 28, 1990, the bus to an ACT UP demo in Albany: I clocked Pierre six or seven rows ahead when he reached his left hand up to … actually, I have no idea what his hand was doing because my eyes were glued to his forearm, which was covered by two wide bars of dense, dark ink. Tattoos were relatively rare then, and this was of even rarer vintage, no barbed-wire bicep band or Celtic tramp stamp but eight or nine inches of yew-green ink that seemed less adornment than abnegation of the flesh. When I saw the fresh pink scar that glowed along the line of his left cheekbone, I whispered to my friend C.B.: I bet he did that to himself. By which I mean that I was turned on (duh), but I wasn’t sure if I wanted to get with a guy who could cut open his own face. With Robbie it was lust at first sight (at least until the blindfold went on). Friday, June 25, 1993, the Backstreet, a leather bar in East London: “He has this great way of kissing,” I wrote in my journal that Sunday, after a follow-up date at the Block on Saturday, “of breathing in and out of each other’s mouths until the oxygen supply is depleted and you get lightheaded. Incredible.” Incredible, but also “alarming”: Colin Ireland, a.k.a. “the Strangler,” a serial killer who’d murdered five gay men in as many weeks, was still at large and, as “strangler” suggests, choked his victims to death, and he did it after tying them up in their homes too—the third unnerving coincidence Robbie shared with him (the first being that the then-unknown Ireland was thought to have procured his victims in bars like the Backstreet and the Block). When Robbie asked if we could go to my place because he had “someone staying/living with him,” I felt a little thrill of fear. It wasn’t until much later that I realized I should’ve been more afraid of his “staying/living” situation. At any rate we couldn’t go back to my place because it was actually Scott’s, and I was sharing Scott’s bed.

At twelve, Lamoine’s body wore adjectives that normally clothe old men’s: spry, wiry, even gaunt. I learned him a limb, a joint, a muscle at a time: the ball of his biceps when he lifted a trash bag from a can; the flare of his shoulders tapering into the skinny of his waist as he led me through a forest of catalpas and cottonwoods; the huge black bruise that seemed to come into being when he pulled off his shirt in an empty locker room. That bruise changed Lamoine for me. With his shirt on he’d been my friend. Exposed, he became like me—someone who knew violence, someone afraid to go home. His mother had fled long before, although Lamoine didn’t seem to have much sympathy for her; he repeated without any detectable skepticism his father’s claim that she’d turned tricks in cars at the foot of their driveway, just out of sight of their house. That funny little house, half-submerged in sandy soil like a coyote’s burrow: it was, as I said, about a mile from mine if you walked the roads, maybe half that if you cut through the fields behind the Hirschhorns’—relatively close by Kansas standards, but far enough that I didn’t find out Lamoine and I were neighbors until a full year after my parents had transplanted us to the country, when I saw him hanging out the passenger window of his father’s pickup as it raced down 82nd Street. I found him the next day at school, I asked if he lived on Tobacco Road and he said yes, I told him I lived on Cottontail and that was that: we were friends. Best friends. Friends for life. It was just a few days later that he showed me the bruise on his back rippling over his ribs like an oil slick rolling in on the tide, massive, deadly, obliterating. How? I asked him, not because I wanted to understand what had happened but because I wanted to contain the spread of this poisonous information. With a two-by-four, he said; and then: Why? I asked, because I wanted to limit the scope of the destruction, but also because I was stupid, or cruel, or maybe just because I was twelve years old. I left the lights on, he said, and then, because his father couldn’t or wouldn’t buy him extra clothes for P.E., he pulled his school shirt back on and ran out to the gym floor. What he needed was some time in a Bacta tank like the one the droid doctors dunked Luke in when Han got him back to the rebel camp. Nix that. What I needed was Lamoine in a Bacta tank, its anodyne serum attending to his marbled flesh while its thick glass wall protected me from same. I was just about to turn thirteen when The Empire Strikes Back came out in May 1980, I’d known Lamoine nine, maybe ten months by then. He was already calling me Bro, which was unsettling to say the least, because one of his brothers was a self-professed murderer and another had drowned in three feet of muddy water and the third hid behind a terrifyingly disconnected Leave It to Beaver grin—by which I mean that L.D. smiled as though he was being double-dicked by his Little League coach and his choir teacher while Mr. Wiebe stood on the sidelines and threatened to shove his cock down his son’s throat if the boy didn’t put a little life into it. So yeah: Bro, and he wanted me to call him Roy, which, like his real name, I remember in its French incarnation: roi. King. But I preferred Lamoine. La moine. The little monk, but feminized—not Lemoine but Lamoine—which is to say: we were both saddled with questions of identity, of who we wanted to be and, even more fraught, who we wanted the other to be, and in that context the scene in the Bacta tank was perfectly calibrated to my sublimated sexuality. In case you don’t remember: the Bacta tank was a phone booth–sized glass cylinder filled with some sort of, um, healing fluid (read: water with an aerator blowing bubbles through it), and Luke was suspended in it by a flimsy silver harness, naked save for a diapery-looking thing swaddling his (surprisingly packed) crotch and a ventilator that covered most of his face. The ventilator obscured Luke’s identity even as the glass wall displayed his lean muscular body. Displayed it, but also rendered it helpless, unable to attack me or fend me off or send me away (things I was always afraid would happen with Lamoine, although I never connected my fears to sex), but also, and more importantly, prevented me from touching him. No matter how much I wanted it—and, weirdly, I was perfectly aware I wanted to have sex with Luke, even as I had no idea I wanted to have sex with Lamoine—no skin-on-skin contact could take place. I could only look. Could only want, and desire in the absence of physical contact could never condemn me. For the next seven years every man I lusted after might as well have been sealed up in a Bacta tank, until finally, when I was twenty, I decided it was time to get it over with already. Thursday, Jan. 21, 1988: as far as I can tell, nothing of any historical significance happened on that date save for the fact that twenty-year-old Dale Peck finally got his cherry popped—although really, what happened between me and Mackie qualified as sex only in the most pedantic poles-in-holes sense of the word. I always stayed at school during breaks. Mackie lived about half an hour away, in Patterson, but he’d returned a few days before the spring semester started in order to break up with his girlfriend, who was also staying on campus, and because he didn’t have access to his own room he slept in mine, in my roommate’s bed. I’m not sure what the issues with Kristen were, but it took them two days to decide they were insurmountable—luckily for me, because I didn’t work up the nerve to accept his invitation? invite him to my bed? until the second night, and even then I was so keyed up I giggled uncontrollably each time he touched me. To his credit, Mackie tried to make it fun for me, but if I was finally ready for sex, I still wasn’t ready for romance or intimacy or even foreplay, and so, after a couple of clumsy minutes, we got down to the serious business of fucking. We had to do it doggy style because if I looked at him I saw my best friend—saw Mackie, my ally in writing classes, my editor at the paper, the first guy to jump on the dance floor when I deejayed in the pub—and I started giggling again. But it was necessary for me to get fucked, despite the lack of lube, or condoms for that matter (which, though conveniently forgotten that night, was one of the things that had kept me from sealing the deal his first night in my room). I wanted the universe to know: I was gay, and what says gay like a dick in your ass? It turned out spit worked fine, especially since Mackie had what is, I think, the third-smallest penis I’ve ever encountered. (Think Susan Minot’s “thin as a thin hot dog.”) When he took his finger out of my asshole and put his dick in and leaned over and asked with what strikes me now as magnificently mature and empathically lucid concern, Am I hurting you? I replied: Are you in yet? (I know: ouch.) Talk about a trooper though: after he shot his load he was nice enough to blow me, and though I’ve slept with a lot of out gay men since, I can’t say that that’s ever happened again. Was I more suave when I met Pierre two years later? Certainly I was less nervous. After six men and maybe a dozen fucks, sex had become less important than the people having it, which is to say: I don’t remember my first time in bed with Pierre, but I remember vividly that first glimpse of him on the bus to Albany, and the second too, which glowed with such an aura of kismet that I felt like I had no choice but to make my play. What I mean is: I’d had a dream that I would fall in love with a man in a lungi, or a kanga, or a sarong (or, well, a skirt), and then I had a dream that I would take a man from another man, and then, on April 28, 1990, a pipe bomb exploded in a trash can in Uncle Charlie’s, a gay bar on Greenwich Avenue that people in ACT UP and Queer Nation looked down on because we considered its clientele apolitical—we thought they were taking advantage of our activism to drink overpriced drinks and dance to out-of-date music and wear, like, sweaters, and so anyway, it was the considered opinion of the New York City Police Department that a bomb in a gay bar wasn’t an act of antigay violence but more likely the work of a jilted lover, which prompted Queer Nation to take to the streets with equal parts righteous anger (against homophobes in general and the NYPD in particular) and condescension (against the twinks in Uncle Charlie’s), and there, in a yellowing T-shirt and battered combat boots and something that looked like a well-used (though not so well-washed) bed sheet wrapped around the lower half of his body was the man from the bus with the forearm tattoo and the scar on his cheek, a month faded now, but still pink as a widowed aunt’s lipstick. I introduced myself, and Pierre promptly introduced the man marching next to him as his boyfriend. Vic, fortunately, lived in Boston, and, as well, he and Pierre weren’t monogamous, so my seduction didn’t exactly qualify as homewrecking. Although really, I’m not sure if I seduced him or, like every other man in ACT UP and Queer Nation, simply fell in thrall to his beauty. At twenty-one his body was just settling into manhood, his meaty ass mounted on thick legs like a pair of Doric capitals, his torso finely drawn and saved from being too thin by wide, strong shoulders. His face was a long oval with a sharp widow’s peak at the top that reminded me of The Vision’s and a pointed chin at the bottom that reminded me of Lamoine’s. In between, though, it was all soft curves: the kind of fat, pouting lower lip people pay money for, a Gallic nose, large moist brown eyes that made me think of the muddy pond where Lamoine’s brother had drowned, which is to say that yeah, they were beautiful, and also melancholy, but when I looked in them I was reminded that eyes are not in fact windows to the soul but rather opaque collagen convexities that do nothing more than reflect the gaze of whoever’s looking into them—but only if they’re looking back. The only hardness was that scar on his left cheek, a pointed reminder that God doesn’t work in straight lines but man does, so, you know, fuck God, because creation can be improved upon. He’d broken a branch off a fallen tree, he told me. He wanted a walking stick, and he pulled the branch toward him instead of pushing it away and raked it right down his face. In the emergency room the attending physician pricked himself with the needle he’d used to inject the topical anesthetic and demanded that Pierre take an HIV test before getting his wound sewn up. Dr. Douchebag didn’t relent until Pierre, who happened to be taking/have taken a medical ethics class at SUNY Purchase, called his teacher, who, like everyone who ever met Pierre, wanted to protect him, and she came to the hospital and had the dumbass removed from Pierre’s case. Pierre slipped up there, he said the hospital was in Queens, where he lived (he’d told me the fallen tree was in Central Park), but the psychological details of the story were so much more compelling than the narrative nuts and bolts that I didn’t catch it, and it wasn’t until years after we broke up that I learned I’d been right. He’d done it to himself. Drawn a razor blade down his cheek, though whether he meant it as an aesthetic expression or a form of self-harm (or both) wasn’t something I felt I had the right to ask him at that point. At that point they weren’t our secrets. They were just his. It turned out Robbie had secrets too. Oh hell, it turned out every man I ever fell in love with had secrets—every one except Lou, thank god—but here’s Robbie’s, in case you didn’t guess it before: the someone “staying/living” with him was his ex, Vaughan, who in Robbie’s telling seemed not to’ve gotten the memo that he and Robbie weren’t together anymore. Obviously, that’s bullshit. Obviously, they were still together in some fucked-up way or another and Robbie just didn’t want to tell me. I knew that even then, but I didn’t call him on it because I was only in London for two months and I wasn’t looking for a boyfriend, let alone a lover, I was looking for a summer fling. What I didn’t count on was falling for Robbie, and even after it happened I remained sanguine—I would go back to New York in August, I told myself, I would remember our affair as a love lesson and a good story, not to mention the first time my sex life corresponded to my (admittedly esoteric) fantasies. And I did go back to New York, and I did remember Robbie, only I wasn’t content to let him remain in the past. Instead, I wrote him, and to my surprise he wrote back, and after seven or eight months of steady correspondence I worked up the nerve (and the cash) to go back to England, and from the first breath-stealing kiss it was clear that Robbie had fallen for me too. That’s when things got fucky. That’s when this machine with three moving parts—me, Robbie, Vaughan—locked into a good old-fashioned love triangle that persisted for another two years. They’d been together six years when we met, the previous five spent on a houseboat in Amsterdam, where they’d moved in disgust when John Major succeeded Margaret Thatcher as PM (this was one of the things that made me fall in love with him). According to Robbie, Vaughan had been a rent boy when they met, a beautiful, brilliant basket case (think Rupert Everett at thirty, but lose the airbrushed coyness and add a couple pints of lager) who never managed to do a damn thing with his life except hold on to Robbie—if there was a Nobel Prize for clinging, Vaughan would win hands down. For the three years my affair with Robbie lasted, Vaughan refused to move out, let alone move on, which is another way of saying that for three years Robbie let him stick around, and stuck with him—stuck by him I want to say—and over time it became depressingly clear that it had taken all of Robbie’s strength to leave Vaughan behind in Amsterdam, so that when Vaughan showed up on Robbie’s London doorstep a few months later, drunk and helpless, bitter and witty and still sexy as fuck, Robbie let him back in and never tried to slip the noose again. Call him loyal, call him a caretaker, call him codependent: whatever it was, it was second nature to Robbie, and it was another thing I loved about him, not least because I wanted it for myself (that would be duh #2). Robbie had raised (his word) his parents, and in his stories they came off as the most pathetic, heartbreaking pair of breeders I’d ever heard tell of. His father had been in World War II, had been a tank gunner and shot his best friend’s head off. He was never the same after that, Robbie said. He made it sound like a miracle that his dad married at all, late in life, to a woman who proceeded to pop out children, three in a row, maybe four, who all died in their infancy. And then the miracle: Robbie, the baby who lived, which inspired his parents to try one more time and resulted in the birth of a severely autistic daughter. After that, it seemed, Mr. and Mrs. P. were just marking time, trusting Robbie to take care of everything till Death took them by the hand and led them the last few steps through the vale of tears, and what with his parents, his sister, and Vaughan, I was determined not to be another weight around his neck. I was twenty-six, after all, I had my own life, I could be patient, I was twenty-seven, my career was flourishing, I was living in London and New York and making trips to Amsterdam and San Francisco and Germany, to the Key West Literary Conference and the Edinburgh Fringe Festival—as an invited author, I mean, not some rando audience member—I was twenty-eight and armed with an artist’s visa handed to me personally by the Vice Consul of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland to the United States of America, who made me wait for eight hours while she cleared out every other petitioner in the British Consulate in New York City, then brought me back to her office and opened a bottle of wine and poured me a glass and apologized for the delay, she’d had to deal with the hard cases first, now tell me about your books, they sound fascinating. I had it going on, okay? My life was a succession of all good things, and I knew that as strong as Robbie was, I was stronger: strong enough to take such parts of himself as he could spare and not ask for anything else unless and until he offered it. But when he asked me to wait for Vaughan to die, I couldn’t do that.

“I was twenty-eight, I had sown my wild oats. I had broken one man’s heart and had my heart broken by another.”

Lamoine ran away the summer after seventh grade. He locked himself out of his house one evening, which is to say, he forgot to carry his key when he stepped outside and his father’s house was equipped with self-locking doors (in case you’re wondering: yes, that was as paranoid as it sounds, in rural Kansas, in 1980). As the sun set and watt-wasting incandescence blasted tauntingly from every window, Lamoine’s ever-present fear metastasized into terror, the terror to panic, and he bolted. Less than twenty-four hours later he was picked up by Child Protective Services, or whatever the Kansas iteration was called, which brokered a deal for him to stay with the family pastor and his wife. He made it almost a year there, and things weren’t too different—we were eight or nine miles apart rather than one, so it was harder for us to get to each other’s houses, but he’d hardly ever come to my house because his dad wouldn’t let him and I’d hardly ever gone to his house because his dad was a fucking sociopath, and plus we still saw each other every day in school, somehow even ended up being the dorks who handed out your choice of white or chocolate milk at lunch, which gave us an hour-plus every day to hang out. But Pastor Tom and Priestess Diane were psycho-Christians of the Bible Belt variety and, as well, they had a new baby of their own, and at some point during eighth grade Lamoine moved in with his mother and stepfather in Halstead, after which I only saw him sporadically—Halstead was about forty-five minutes from Hutch, and my parents had better things to do than drive me all the way there to hang out with my juvenile delinquent friend. On one of my visits, however, I did meet his oldest brother, who was maybe nineteen or twenty, and who boasted of being a gang member in Kansas City and of having killed three men. Then I guess Lamoine ran away again, was picked up again, made the rounds of a few juvenile facilities and foster homes, some of which I saw, some of which I didn’t, until, at age fourteen, he just disappeared. From my life and, I have to admit, my mind too. I was a freshman in high school by then, I’d finally realized what I was: I was (wait for it) a nerd! Hallelujah! For the first time in my life I had a (marginal but acceptable) social identity, I had a circle of friends and, perhaps most importantly, I had joined the debate team and, surprise, surprise (haters, get ready to gloat), this pathologically shy and terminally frightened boy turned out to have a flair for standing behind a podium and tearing apart his opponents with a mixture of reason and rhetoric and something he didn’t know was schadenfreude, even though he really got off on it. Within a few months I’d caught the attention of the captain of the squad, who plucked me out of the novice circuit to groom me as his successor (“his” being accurate if anachronistic, because the debate captain, a transman, was then still living as a girl), and so anyway, I was a big fish in a small pond—a pond as small and shallow as the one Lamoine’s younger brother had drowned in while Lamoine slept on shore—but even so, those first successes were enough to instill me with confidence, to direct my attention away from my miserable childhood (I was a teenager now, I was practically an adult) and toward a future that for the first time seemed filled with open rather than closed doors. But then, a year or so after he disappeared, Lamoine was back, driving a massive Chevy Blazer equipped with Texas plates and a cowcatcher that wouldn’t have been out of place on the front of a freight train—oh, and a loaded gun in the glove compartment too. He was a tiny boy, five-five maybe, five-six, a buck-fifteen soaking wet, and when he pulled into our driveway he was squinting over the steering wheel like a little old lady looking for a toddler to run over. He told me that the man at his last foster home had sexually assaulted him (months later, after Lamoine was locked up in juvie, I saw a newspaper article confirming his story), and he said that after he ran away he made his way down to Houston, where he’d been working for the past year as a prostitute. He told me his clients were women and I believed him, despite the fact that he also told me he’d been living most of that time with “a gay guy” who sold him the Blazer (traded it, actually, for Lamoine’s stereo), which smells fishy, I know, which now that I think about it makes a helluva lot less sense than Pierre’s I-cut-my-face-when-I-broke-a-walking-stick-off-a-fallen-tree or Robbie’s He’s-just-staying-till-he-finds-a-place-of-his-own, but at the time it didn’t occur to me to question anything Lamoine said, I was just grateful he was back, and without thinking about it I threw over my new friends and my new identity and we fell into the pattern we’d established two years earlier, spending every waking moment together—yes, and every sleeping moment too, because he bunked in my room, one of us on the bed, the other in a sleeping bag on the floor, safely zippered away from a physical exchange that I still didn’t know I wanted, though I suspect he did (know I wanted it, I mean, not want it himself). On July 4th we drove the Blazer into Hutch to watch the fireworks from the fairgrounds, but the real excitement came after we left, when Lamoine punched the gas to make it through a light and the accelerator jammed. The streets were clogged with hundreds of cars, and we must’ve run a half dozen red lights on the way out of town, zigzagging around slower and stopped vehicles yet somehow never even nicking a fender or breaking off a side mirror, let alone attracting the attention of a police officer. Lamoine rode the brake with both feet while I crouched on the floor of the cab and tried unsuccessfully to pry the accelerator loose until at last we made it across the four lanes of Highway 61 on the east side of town and screeched around the long south-turning curve where 17th Street yields to Airport Road and suddenly found ourselves on open empty asphalt stretching off into the vastness of the plains. The whole weight of Lamoine’s body on the brake was barely able to hold the truck to forty-five, fifty miles an hour. I was back on the seat by then, I was staring into the narrow tunnel the headlights carved out of the darkness. A part of me wanted Lamoine to stop resisting, to give the truck its head like a horse that’s taken the bit and let the Blazer deliver us to whatever fate it had in mind, escape, death, Oklahoma—Texas even—but another part of me was more … rational, I guess, and that part of me suddenly remembered a scene from ChiPs (hand to God) where this same thing had happened, two girls in a little convertible import, Jon yelling at them from his Harley to downshift the automatic transmission, and that’s what I told Lamoine to do, D to D2, I told him, D2 to D3, and, engine screaming louder and louder, the truck began to slow until we were down to about twenty-five, at which point Lamoine steered the Blazer off the highway and drove us into a telephone pole (which took more damage than the ridiculous cowcatcher welded to the front of that ridiculous grill). The engine shrieked as though it was going to explode and we jumped out of the cab and started to run away and then something lurched under the hood and the truck hopped in the air like a startled cat and spat fire from its exhaust and stalled out, and after a moment of stunned silence and another, longer moment of hysterical laughter we climbed back in the Blazer and hey, it started up just fine! Elated and exhilarated, we drove back to my parents’ house and took up our posts for the evening, one tucked into the bed, one zipped into the bag on the floor, which I can’t help but see now as another iteration of the Bacta tank, a necessary barrier between me and what I wanted, or rather what I didn’t know I wanted, by which I mean that it was only after Lamoine was gone that I regretted not squeezing him onto my bed and letting proximity and adolescence do its job—but this regret produced its own kind of torture, made me hate myself for wanting something I knew I shouldn’t, because Lamoine wasn’t gay, and though I think he might very well have given me what I wanted, I think too that it would have destroyed whatever existed between us, because the sexual transaction would have been just that: a quid pro quo in which he gave me his body in return for the right to call me Bro. It would have been too close to what he’d been doing in Texas, in other words. Though the finer points of his sojourn into hustling (i.e., the sex of his clients) remained unknown to me, or rather unacknowledged, the horror of what he’d done was present in the way he spoke of it, which is to say dispassionately, his voice as flat as when he told me that his father had broken a two-by-four over his back or his mother had turned tricks down at the end of the driveway or his little brother had drowned in three feet of water while Lamoine, who was supposed to be watching him, slept at the edge of the pond. It’s not so bad, he told me late one night, his gaze directed out the window and fixed on some unseeable point in the dark forest that surrounded my house—on the recent past perhaps, when a bullet from the gun in the glove compartment of the Blazer had pierced the back of one of his johns, or the distant future when, a full thirty years after he first ran away from home, he finally pointed the gun at the man he really wanted to shoot. They pay you, it’s quick, he told me. It’s not so bad. Five days Lamoine stayed at my parents’ house, maybe six, a minuscule period of time in a childhood as long as mine already was, as complicated (one father, four mothers, three whole-, half-, and step-siblings who counted five biological parents between them, eight moves across three states by the time I turned nine), but however short his stay was, it was also the hinge to a destiny that really probably should have been mine, by which I mean that the only thing that stopped me from driving off with Lamoine in that gas-guzzling four-wheeled vehicular defense against accusations of inadequate masculinity was that he hadn’t bought the Blazer, let alone traded it for his stereo (although that is, now that I think about it, exactly the kind of thing a homeless fifteen-year-old hustler would spend his money on): he’d stolen it. (This would be duh #3 for those of you still counting.) It was a day or two after the fireworks show. Lamoine got pulled over for speeding, and from the moment the lights flashed in the rearview he started to freak out. I didn’t get it—in my mind he had no parents to get in trouble with, so what was the big deal?—until five minutes after the cop had given him the ticket and we’d driven away and the lights were flashing behind us again, not one car this time but two, three, finally six, i.e., a sizable chunk of the Hutchinson PD. Before I knew it, we were surrounded by a half dozen cops who approached the Blazer from every direction. They took Lamoine into one of the cruisers but left me in the truck, and the whole time I sat there—ten minutes, two hours, I have no idea—I was acutely conscious of the fact that the pistol Lamoine had brought with him from Texas was in the glove compartment, loaded with bullets and fingerprints, his and mine, commingling on the crosshatched grip in a way that unmasked me as the degenerate I was, and then a cop came and took the gun away, and then another cop came and took me home, and during the drive he told me that Lamoine was wanted in Texas for grand theft auto, which I’d kind of figured out by then, and attempted murder, which, you know, kind of surprised me, kind of made my head explode a little, kind of made me wonder what the hell had happened to my best friend in the year he’d been gone. I mean, I’d held the gun. I’d fired it. It was a .22, but I thought of it as a Derringer because it was so small, so harmless, a theatrical prop rather than, you know, a weapon. From fifteen feet away its bullets didn’t leave a visible impression in the bark of the cottonwood we set my parents’ empties against, which is probably why Lamoine was tried as a child rather than an adult, why the charge was attempted murder rather than murder two. It wasn’t until after he’d been sentenced (two and a half years in juvie) that I found out what had happened. He told me via letter that a man had offered him a ride home and tried to rape him, forcing Lamoine to pull out his gun, forcing him to pull the trigger, which story might have been more believable, not to mention more sympathetic, if the man hadn’t been shot in the back—twice. Which is to say: I wasn’t falling for it by then. By then, I was able to read between the lines. By then I understood Lamoine’s clients hadn’t been women and the gay guy he’d lived with hadn’t let Lamoine stay with him out of the goodness of his heart and the man Lamoine had shot hadn’t simply offered to give Lamoine a ride home. I understood that the boy I was in love with, the boy I thought of not as my brother but as my alter ego, my shadow, the fleshly manifestation of my sorrows and suffering, of my fantasies of revenge and escape, the boy who had run away so that I could stay, had for the past year been keeping himself alive by selling his body to grown men, and I thought that’s what it meant to be gay. Not Lamoine—Lamoine wasn’t gay—but me. Me and the perverts who didn’t so much offer Lamoine money for sex as coerce him to accept their dollars along with their dicks so they could hide behind the transactional illusion that the teenaged boys they raped were, if not exactly willing partners, then at least consensual. And though I knew I was gay by then, I knew too that I would never let myself be one of those men, but I didn’t know what alternative that left me, what other ways there were to be gay. Is it any wonder that I continued to confine my fantasies to men safely locked behind walls of glass, be it Luke in the Bacta tank or various actors who lived only on the far side of TV and movie screens? Such homosexual feelings as I recognized (and by recognized I mean jerked off to) were directed at boys and men who populated a succession of mostly really sorry movies, and in their cleaned-up TV edits to boot: Christopher Makepeace in My Bodyguard, Lawrence Monoson in The Last American Virgin, Doug McKeon in On Golden Pond (and even more in his anti-drug TV movie Desperate Lives, where he played a member of the swim team and spent a lot of time in a speedo). God only knows why the boys in the “Total Eclipse of the Heart” video shed their school uniforms for, um, loincloths (well, God and Russell Mulcahy, the video’s gay director), but I ate it up just the same. Or that moment in the “Love Is a Battlefield” video when thirty-year-old runaway Pat Benatar lingers at the top of a Port Authority escalator and a man in leather pants emerges like a hellborn demon and pushes past her as if she isn’t even there. Dog chain coiled around his waist in lieu of a belt, red hankie hanging from his back left pocket like a secret sign: it would be years before I learned that the hanky told anyone in on the code that Leather Pants was a fisting top, but even then that shove, the complete indifference to Benatar’s sexual appeal, and the presence of a second, half-glimpsed male figure behind the first, similarly dressed and trailing behind his man as submissively as if the dog chain wrapped around his waist had been looped around his throat instead: the three- or four-second scene made my dick twitch every time. Or, Jesus, the nightclub in “Relax”: the leather, the rubber, the leashes, the Catherine wheel spinning dizzily at the end. The one or two times I was lucky enough to catch it, I had to pull a pillow from the couch over my lap. Like Luke in the Bacta tank, these images were safe fodder because they clearly weren’t real, so nothing could come of them save the spilled semen that crusted a rag I hid behind my bed until, at length, my stepmother told me, not unkindly, that she could smell the damn thing whenever she went in my room and would I please just put it in the laundry. No surprise, then, that the sexual fantasies I didn’t borrow from videos and TV shows and movies, the narratives I made up myself, involved kidnapping, imprisonment, isolation, and coercion, and even though I rarely allowed myself to contemplate intercourse itself (the reality of putting the thing that you pee with into the hole that you poop from was for most of my teenaged years too much for me to confront even in my imagination), whatever physical contact did occur in my fantasies was always against my will, which is to say I couldn’t be held accountable for it. I couldn’t be blamed, and I couldn’t be punished. It wasn’t until my senior year in high school that I allowed myself to acknowledge a crush on an actual person, my debate partner, a boy named Alan whose future I’ve often wondered about, given the fact that he liked to wear not-quite-clear nail polish (he said it made them stronger, which helped with his guitar playing) and, despite his high grades, skipped college to become a hairdresser (he said the money was good). But nothing happened between us—nothing was even hinted at beyond a shared interest in the International Male catalog—and then we were graduating and when I came home the summer after my freshman year at college Alan was (come again?!) married. Like Alan, Mackie was Levantine (Alan Lebanese, Mackie Syrian). Mackie’s father was first-generation while his mother traced her roots to the Mayflower, a less-than-typical pairing at that time. Most people think I’m Puerto Rican, he told me, and he was semi sort of more-or-less content to let most people think that, but what really made his family unique, at least to me, was the fact that everybody seemed to like each other. I know, crazy, right?! Still, some part of Mackie must have perceived his family’s love as conditional, because he’s kept the homo aspect of his sexuality hidden from them for going on forty years. I don’t mean that Mackie’s gay—he’s one of the few people who calls himself bisexual whom I actually believe—but when the gay side of his sexuality strayed from the confines he’d deemed safe—which by that point meant New York City, where as far as I know he only slept with men—he grew defensive, changed the subject or denied it or just plain sold himself out. I remember one time in college when he reamed out a student in a writing class for saying that it was natural to get nervous when men in keffiyehs board your plane, and though I agreed with him (even though I knew I’d’ve probably gotten nervous too), I didn’t understand why he was so upset. I’m Syrian! he shouted at me after class, as if I was retarded. The declaration stuck with me, or rather the anger: it was the first time I was aware of someone acting from a sense of identity larger than his person. I was white, I was male, I was nominally middle-class and ostensibly straight, by which I mean that I’d never had cause to think of myself as someone with an ethnicity or a gender or an economic status, had never considered the power of the tribe, the sense of righteousness that comes with solidarity, particularly when it’s with the minority—which made the betrayal that much greater when, a few years later, over dinner at Mackie’s parents’ house in Patterson, his family launched into a round of gay jokes at my expense and instead of defending me he hopped on the bandwagon. It started innocently enough: Mackie’d just bought a motorcycle jacket and, like a business announcing its wares on a sandwich board, he put out his sign, or rather signs: a pair of cock rings hung off the jacket’s epaulets (the rings were an extension of the hankie code: one on the right shoulder meant you were a bottom, one on the left meant you were a top, one on each side meant you were vers). Talk about clutching: when one of his five? six? siblings asked him what the metal rings were for, Mackie stammered some sitcommy nonsense about how you could tie a rope to them and pull the jacket behind the motorcycle he didn’t own in order to scuff it up a bit. The B.’s were homophobes but they weren’t stupid—weren’t that stupid anyway—and they grilled him for a while until finally I told them that the thick shiny loops of stainless steel were cock rings—which is, I’m pretty sure, the first and last time that term was used at the B.’s dinner table. This led to a round of genial but far from benign jokes (before I’d arrived, in fact, Mackie had told his mother that we were looking for an apartment together, and she’d asked, not ironically, if Mackie was afraid that I would, say, leave a butter knife on the counter—i.e., that I’d give him AIDS) and now, glad to be out of the hot seat, Mackie joined in the gay-baiting eagerly, until at length I leaned over and whispered in his ear: I’ve seen cum dribble from those lips so I’d watch what you say. Which wasn’t quite true—in fact, Mackie’d swallowed every drop—but, in an Alanis Morissette ironic turn of events, my threat did produce the only genuine spit-take I’ve ever seen, and it’s the comedy of the evening that’s stayed with me, rather than the homophobia. A few years earlier the scene might have hurt my feelings more, but I was living in New York by then, I had a political consciousness (not to mention a sex life) rooted in experience rather than daydreams, and I felt worse for Mackie than I did for myself. Or maybe I just had more immediate concerns: I’d broken things off with Pierre by then and was still trying to figure out why. Why in the hell had I ditched the best thing that had ever happened to me? According to my journal, I broke up with Pierre because “I wanted sex w/ other people.” But of course that’s a lie, a half-truth at best (say hello to duh #4). I broke up with Pierre because I wanted to find out if the sexual fantasies I’d been having since I was twelve or thirteen were nothing more than a coping mechanism, a response to the virulent homophobia of my home, my school, my town, my state, my country—if they’d functioned as a way to keep me from engaging in homosexual intercourse, in other words, so that my father or some redneck (or virus) didn’t kill me—or if they were instead something I actually wanted to do. (It didn’t yet occur to me that they might be both.) By that point I’d lived in New York long enough to understand that the activities I fantasized about weren’t impossible. Nor were they the sexual equivalent of, I don’t know, the Chicxulub asteroid, but were in fact fairly common, and, like so many formerly marginalized behaviors, were in the process of being transformed from individual, isolated impulses into a self-proclaimed community by the identity-based civil rights movements of the 1980s (with a strong assist from late twentieth-century capitalism, which regarded sex as ripe for commodification). Every Monday night at ACT UP I was reminded by a neat (if aesthetically horrific) logo stenciled on the seatback in front of me that the chairs we sat in had been paid for by Gay Male S/M Activists, and I’d even peeked into their meetings in the Center once or twice, but the men were—the horror! the horror!—middle-aged, and fat and hairy too, and, well, there was just something silly about a group of fifteen or twenty old guys standing around a snack table with their harnesses cutting up under their sagging chests like ill-fitting bras and cackling about the way Jessye Norman’s ombré bustle skirt in Ariadne auf Naxos made her look like a gigantic popsicle—which is to say, I was just starting to accept the idea that it was okay to be into something a little kinky, or a lot kinky as the case may be, but I couldn’t bear the fact that it was kitschy too. The guys who stood outside the Spike and the Eagle on Friday and Saturday nights came in a wider variety of shapes and sizes and ages than the ones in the Center, and in lieu of urbane conversation there were just hard stares as I cycled around the block once, twice, a third time before chickening out and heading home to jerk off to what I wished had happened, and if that sounds a little quotidian, a little dull even, I think that was the point. By then my fantasies had moved past the science fictional contrivances of my adolescence for the encounters I read about in used copies of Drummer and Bound and Gagged that I bought from a sidewalk vendor on Astor Place, which published stories that, like me, had abandoned farfetched setups for scenes rooted in the contemporary world of BDSM, a transformation that robbed the acts of a good portion of their psychological power but for the same reason made them much less threatening or disruptive, both to their individual practitioners and to the larger culture. I was moving my fantasies closer to reality is what I’m saying, incorporating them into an identifiable social context, a community, a body politic, which, like every other subset of gay life in the 1990s, came with its own bars and clubs, its own social organizations and newsletters and political agenda and jargon. The (literally) alien worlds I’d fantasized about as a teenager were replaced by leather bars, the kidnapping and rape scenarios gave way to a stilted but politically expedient vocabulary of consent—“play,” “scene,” “safe word”—the equipment and accouterments changed from Bacta tanks and stillsuits to the leather and rubber and stainless steel implements available at the Leatherman and the Noose, which establishments, though filled with whips and dildos and cock pumps and “video head cleaner,” were nevertheless run with the fraternal air of Savile Row haberdasheries, albeit ones in which traditional tailors’ inquiries such as “Does gentleman dress to the left or to the right?” and “Would gentleman prefer buttons or zipper?” were rendered as “Which side does your dick fall on?” and “Do you want the codpiece in leather or metal or do you just want to let it all hang out?” But despite all this, the closest I’d come to acting on my fantasies was buying a pair of handcuffs, cheap tinny bracelets you could pick with a paper clip. I pulled them out one time when Pierre and I were in bed and he laughed at them, professed a certain curiosity, a willingness to give them a try, but it was clear something about them made him uncomfortable, by which I don’t mean nervous as much as, well, terrified, and so that was pretty much that. It wasn’t until we were at a party sometime later in our relationship that I learned why the handcuffs had freaked Pierre out so much. We were sitting on the floor of Rod Sorgé’s living room, which was a familiar place, a safe space to use the parlance, an apartment where we’d assembled bleach kits a dozen times and where we were now surrounded by friends who were mostly from ACT UP and mostly from Needle Exchange, and in a way that I didn’t quite follow, the usual party banter somehow fell by the wayside and I suddenly clued in to the fact that Pierre was telling our friend Zoe that he’d been raped when he was in eighth or ninth grade. A posse of boys had grabbed him, he told Zoe, some of them formed a wall between him and the students going up and down a stairwell of his Roosevelt Island school while another one did the deed, and after the rapist-in-charge finished he told Pierre: I just wanted you to know what your life as a fag was going to be like. Pierre was twenty-one or twenty-two at the time he told Zoe this story, it had been six or seven years since the rape and we’d been dating for several months and I thought there was something real between us, something deep, something enduring, and there was, but there was also this: Pierre would not look at me while he spoke to Zoe. I don’t remember if he was touching me but I assume he was: he was always touching me, not sexually, or not just sexually, not possessively, not needily, not in any way other than as a simple sign of affection and connection, and this aspect of our relationship had always been among the most precious of the things he gave me. I remember when I was thirteen and, six years after we’d moved away from Long Island, my father drove us back for a visit and I saw my former stepmother for the first time since she’d fled her marriage. Terry threw her arms around me on the front lawn of Aunt Peggy and Uncle Jack’s house and, after hugging her briefly, I let my arms fall to my side while she continued to squeeze me tightly, fiercely, as if she wanted to make up for all the times in the past six years she hadn’t been able to touch me—to comfort me, confirm me, protect me, or just show me how much she cared. And it’s not that I didn’t like her embrace, or wanted to flee it: I simply didn’t know how to return it. I didn’t know how to touch another person. In my family, people only touched each other in anger, in violence, and this violence had a sexual subtext that I felt more than understood, and so I avoided touching people in any but the most formalized circumstances, a handshake, a communion wafer, and even then a part of me felt I was violating a cultural boundary on a par with the incest taboo or the rural prohibition against trespassing, which is to say that I believed two people, whether strangers or family, couldn’t touch one another without profound discomfort, and that anyone I laid a hand on was perfectly within his or her rights not just to recoil but to assault me in order to remove my hand. When, seven years after that trip to Long Island, I giggled and shivered through the loss of my virginity, it was clear I still hadn’t learned how to touch people, how to be touched by them, and it wasn’t until I began dating Pierre two years after Mackie fucked me that I finally learned to accept another person’s touch, to touch another person, and my gratitude toward Pierre for this gift was so powerful that sometimes when he absently ran his fingers over my cheek or arm or ass I would want to weep with a joy that is, I think, purer than any emotion I’ve experienced since my mother died when I was three. So yes, we were probably touching. But suddenly that connection lost its power, its meaning, because Pierre could not look at me while he told Zoe about the rape. Suddenly I realized that Pierre’s physical affection came with its own baggage, was consciously or unconsciously a way of forestalling inspection of certain aspects of his past that he didn’t want to look at or explain, most noticeably that fraught year or year and a half in his adolescence when he realized he was gay and his father died of cancer and he was raped in a school stairwell. I knew about his father, if sketchily, that he’d been a chemist and that Pierre was studying chemistry and that Pierre sometimes broke into the chem lab at SUNY Purchase and, wrapped in his father’s long wool winter coat, curled up to sleep on a slate table, but these acts struck me as not just transparently symbolic but performatively so, by which I mean that it was pretty obvious (to me if not Pierre) that Pierre did these things so he could tell people he’d done them and in this way talk about his feelings about his father’s death without having to talk about his feelings or his father or death. But there were no theatrics where the rape was concerned, no symbols, or if there were, it was only this: none of your business. Though Zoe and also our friend Kimberly asked him questions, and Pierre answered them, I felt shut out of the conversation, muted, and instead of talking I found myself thinking about the tilework in the floor of the landing outside Rod’s apartment. Rod had pointed it out with great tenderness the first time we came over, an intricate and elaborate pattern of blue and red hexagonal tesserae that proudly informed you that you’d reached the “3th” floor (the first was labeled the “1zt”), and we had talked about how fifty or a hundred years ago an illiterate or perhaps non–English speaking mason had with obvious care and pride miscopied this sign, yet still managed to get the message across—managed to tell you where you were but also to tell you a little something about himself, which, you know, was a lot more memorable than plain old “3rd.” What I mean is, I understood what “3th” meant even if the mason didn’t, but I didn’t understand if Pierre was, in the same way, unwittingly sending me a message, or if he was merely talking to Zoe and Kimberly because he was talking to Zoe and Kimberly—because he’d been, you know, raped, and these revelations have their own way of choosing when and how and to whom they’ll come out. But though I nudged him once or twice in the following weeks, I didn’t get anywhere, and soon enough I gave up trying to get him to tell me what was going on, gave up on him really, gave up on us. For the first two or three months of our relationship I’d devoted all my energy to pursuing Pierre, who allowed himself to be caught over and over but always bolted as soon as I let go, until finally I called him out, told him that it wasn’t me he was running from but himself, and not only did he cop to it, he caved, and never tried to run again. But once I finally had him, I didn’t know what to do with him, or with myself. At twenty-two, twenty-three, I’d learned how to chase a man, how to catch him even, to touch him and be touched by him, but I still had no idea how to be with him. It wasn’t my interest in S/M that made me break up with Pierre, in other words—we had an open relationship, after all, and I could have easily explored it on the side, could have told him about it or kept it from him as the situation dictated. It was, rather, my inability to be honest about my sexual predilections coupled with Pierre’s inability to open up about his past, or at least the effect that past events still had on him—his palpable fear when I produced the handcuffs, or the disconcerting way he sometimes laughed uncontrollably after he came, but only when I fucked him. We didn’t trust each other, in other words. I don’t know why Pierre didn’t trust me, and, frankly, it’s none of my business now. He never misled me or promised me anything he had no intention of delivering, and, you know, it was thirty years ago and we dated for, what, seven whole months? No, only my motives concern me now, and only because at this point in my life they seem so silly, and so truly, terribly pathetic. “I wanted to know that someone else could love me as much as you did”: that’s what I wrote in an unmailed letter to Pierre on Nov. 4, 1991 (wrote it in my journal actually, i.e., wrote it to myself), and thirty-two years later it still strikes me as one of the most damning things I’ve ever written or even thought about myself, a confession of self-doubt and self-loathing, of an infantile all-consuming emotional hunger that could never be satisfied, and likewise the single best thing I ever did for myself was to recognize that need as a vestigial injury dating from the murder of my mother, a phantom pain in an amputated limb that could neither be recovered nor relieved but had instead to be accepted for what it was. Which, you know, is easy for me to say now, but took a good four or five years to work out then—took me until the middle or maybe even the end of my relationship with Robbie, whose love was the affirmation I needed even as it only complicated my life, and his, and Vaughan’s. What I mean is: after two and a half years I knew that Robbie was the perfect combination of kindness and kinkiness, dirtiness and domesticity, and that I wanted to spend the rest of my life with him. What’s more, I knew my waiting game was working, that the life I offered Robbie was not only more appealing to him than the one he had with Vaughan, but that Robbie was finally realizing he could have it, that he wasn’t responsible for Vaughan’s misery and didn’t have to remain chained to it for the rest of his life. The only problem was that Vaughan had realized it too. Had recognized that slowly but surely Robbie was easing him out of the flat on Keogh Road and easing me in, and to forestall this possibility once and for all, Vaughan came up with a bold plan, a brilliant plan really, a queen sacrifice for the sake of a stalemate that he played like a fucking Grand Master. He enlisted one of their friends, Teddy, as an unwitting ally—one of our friends, I should say, because I knew Teddy by then, by then I knew almost all of Vaughan and Robbie’s friends, except now they were Vaughan and Robbie and Dale’s friends—although really, if Teddy was anyone’s friend he was Robbie’s, was in fact one of Robbie’s best friends, and he’d just found out he was HIV-positive, and while Robbie’s reaction was one of commiseration and sorrow (this was 1994 or 1995, when combination therapy remained an undreamed-of future), Vaughan’s reaction was to get Teddy to fuck him without a condom. Once, more than once? I don’t know. I don’t care. Scratch that: I don’t give a fuck. But the instance that Vaughan chose to describe to Robbie, and that Robbie relayed to me, had taken place on Teddy’s motorcycle, or maybe Vaughan’s motorcycle (motorcycles being to Robbie what the Bacta tank was to me), and it was presented with the saturated heat of a Kenneth Anger film, a pornographic act cum religious sacrifice doused in alcohol and set afire. Life was being taken from one body and given to another, Teddy’s tainted jizz was the Eucharist crossed with forbidden fruit and all who partook of it were forever marked out from other men. No doubt there were other encounters, with Teddy, with random idiots and drunks and drug addicts too fucked up to care about themselves or their partners, but this was the one Robbie remembered. This was the one he told me about—Vaughan using one of Robbie’s best friends to bind himself to Robbie more tightly than any pair of handcuffs could ever manage. This might not seem self-evident unless you knew Robbie as well as Vaughan did, which is to say that after he got his test results Vaughan told Robbie that if Robbie left him he’d refuse to take his meds and let himself die, or who knows, maybe Robbie made that leap on his own, but in either case Robbie, being Robbie, couldn’t bear that, couldn’t call Vaughan on his bluff or just say fuck it, go ahead and die you moron, you’ve already wasted your stupid fucking miserable excuse for a life so why don’t you just die already? It would be Robbie’s fault somehow, for not caring enough, for caring too much. Yet Vaughan’s death was what he wanted. Was the only thing that could set Robbie free. He’s not well, he told me, after I came back to London in early 1996 from the American publication of The Law of Enclosures, and there was no affection in Robbie’s voice when he said this, or sadness. Only guilt—guilt and a kind of wistfulness a less charitable man might call hope. He’s different now, Robbie told me. Thinner. Weaker. I can’t see him lasting very long. (He turned out to be wrong about that. He wasn’t wrong about much, but he was wrong about that.) You’re asking me to wait for him to die, I said, and when Robbie said, Let’s not be maudlin, I got angry with him for the only time in our relationship, and I held on to that anger for the next three years because it was the only thing that kept me from calling him, from jumping on a plane and showing up on his doorstep and saying yes, I would wait, however long it took for Vaughan to succumb, I would settle for Robbie’s crumbs because they were more fulfilling than anything I got from anyone else, I’d hide Vaughan’s medicine, I’d get him drunk and send him off on his motorcycle, I’d poison his drink or cut his fucking throat, I’d drink his blood if I had to, if that was what Robbie wanted, if that was what it took to get him to love me, I would infect myself and deposit myself on his doorstep like another of the epidemic’s orphans, severed from the past, erased from the future, existing only in a cloistered present in which Robbie held me in his arms and nursed me out of this world.

Looking back, I realize that was the end of my youth. I was twenty-eight, I had sown my wild oats. I had broken one man’s heart and had my heart broken by another. I had confronted for the first time as an adult a person who would not let himself be happy, but that person wasn’t Robbie, or wasn’t just Robbie: it was me. It was the man who had, ever since that first glimpse of a half-naked Luke Skywalker sealed up in the Bacta tank, learned to compartmentalize love and sex. Sex was something you had with a body and love was the fantasy with which you clothed the experience and made it emotionally chaste, so that when you were fucking it was only the body you had any real experience of. Personality—personhood itself—was replaced by an idea that you projected onto—into—the flesh that coupled with yours. It was this disconnect that led me to leave Pierre in search of someone who could love me as much as he had. That search led me to Robbie, who, yes, loved me as much as Pierre had, maybe even loved me more, but the simple truth I didn’t recognize until long after the fact was that, all context aside, Robbie didn’t love me as much as he loved Vaughan, just as I didn’t realize until years later that the person whose love I was really looking for was Lamoine, who after his release from juvie at age eighteen had disappeared once again, and hadn’t been heard from since. I had thought these kinds of intractable daisy chains belonged to my parents’ generation—to breeders, to bigots who denied themselves the same happiness they denied other people. I’d believed in a utopian ideal of gay psyches and gay culture, of the inevitable upward trajectory promised by the coming out narrative. I thought that being gay meant that you were more self-aware than straight people, more energetic in the age-old quest to find your place in the world, physically, culturally, existentially, but after Robbie I understood that the real barrier to happiness wasn’t social or external. It was personal. It was inside you. Mackie would always lead a cloistered life with his family and Pierre would always need the solidity of a slate table to remind him he wasn’t fatherless and Lamoine would always need a gun in his hand to make him think he was. The Bacta tank was filled with water, after all, not magic, and my faith in its power would never heal the various men I’d imagined inside it, and wouldn’t heal me either. Whatever insight I’d gleaned from my relationship with Robbie, it hadn’t added to who I was, hadn’t made me a better person, a bigger person, more mature, more well-rounded, ready to use what I’d learned to find someone who was right for me. All it had left me with was the feeling that there was less of me than there’d been before. Or at least that’s what I felt in 1996 or ’97 when I first wrote about our breakup. I wrote about my breakup with Robbie three or four times, actually. It’s the only one I’ve ever written about, at least in nonfiction, and with each new examination I found myself putting it into a larger and larger context, but it took me a good ten years—took meeting Lou—for me to realize that when I broke up with Robbie I had also broken up with my past. With the way I’d handled all my relationships up to that point. It’s not that there was less of me than there had been: it’s that I’d always been less than I thought I was. That the fantasies I concocted were about me as much as they were about my partners. That an illusion of invulnerability and invincibility had enabled me to do amazing things, things I couldn’t have done otherwise, whether it was tying a twenty-five-year-old boy named Keith to a tree in Mile End Park and whipping him with his own belt while drunken skinheads walked home from the pub not twenty feet away—yes, and afterward holding him on the grass while he told me he was dying—or writing a story about the same encounter so that some part of Keith would remain if he did in fact lose his battle with HIV. Lamoine and Mackie and Pierre and Robbie—yes, and Luke Skywalker, and Keith, and that guy at the World who asked me if I knew Chrissy (Chrissy who? Chrissy Snow. Chrissy—oh), and the guy I met in Munich who told me he’d modeled for Tom of Finland and had the dick and the body to back up his claim, and the guy who would only go to the Key West Literary Conference with me if I’d sign a slave contract and wear a padlocked collar around my neck. Hundreds of men, thousands, counting the sex club encounters, a veritable pride parade of tops and bottoms, twinks and bears, fetishists and fantasists who, despite their differences, seem in hindsight like so many aspects of a single relationship. Not a single person certainly—it was their differences one to the next that made them special to me—but as the years have gone by and the big picture has inevitably faded from memory, it’s the little distinctions that have stuck around, a scar, a smile, a haircut, a dick or an ass, a story, and these remnants have melded together into a composite entity like the statue in King Nebuchadnezzar’s dream, golden head, silver chest and arms, bronze stomach and thighs, iron legs, and—oh yes—feet of clay. What I mean is, I’m aware that what I’ve written here doesn’t do these men justice or pretend to objectivity, let alone holism. Though I can tell you that after the Star Wars trilogy Mark Hamill more or less disappeared from the screen (and from my fantasy life), and that after he got out of juvie Lamoine racked up, by one account, twenty-five convictions for a variety of nonviolent, usually drug-related offenses until, in 2011, he finally shot his father, firing twice as he did with the john he shot when he was fifteen, but using a shotgun this time, with fatal consequences; can tell you that Pierre moved to San Francisco after we broke up, landing in a quaint, loving, polyamorous relationship with a pair of men named Kipp and Patrick, and that Mackie contracted hepatitis three years after he moved to New York and fled back to Jersey, where, within a year, he was engaged to a woman with whom he now has three children, and that Robbie is, to the best of my knowledge, still with Vaughan—still living with him anyway, and still trolling fetish sites for men to have sex with—I also have to tell you that these outcomes, though not necessarily unexpected, are nevertheless not inevitable. What I mean is—what I hope is obvious—the stories I’ve told here aren’t their stories, no matter how much I’ve said about them, but mine, because whatever else these men are in their own lives, they’re also a part of my story, are, indeed, a part of me. And he asked him, What is thy name? And he answered, saying, My name is Legion: for we are many. It’s true: the memory of first love is like a possession, but don’t confuse these words with exorcism or any other attempt at voiding. I’d fight tooth and nail if anyone tried to cast my demons from me, I’d twist my head around and spew torrents of bright green vomit, and if it seems that the lady doth protest too much, then maybe it’s because, as much as I cherish these memories, as much as they torment me, I also wonder if they really are a part of me anymore, or if in fact they exist only on the page. But even as I think that, I think of a summer evening when Pierre and I ended up at the Bar on Second Avenue and 4th Street, and because money was short we bought only one bottle of water to share between us. The bottle was in Pierre’s hand and he took the first drink. I expected him to hand the bottle to me but instead he pulled me close with his free hand and pressed his lips to mine and passed me the water that was in his mouth. I knew immediately that I shouldn’t swallow the water but pass it back to him, and I did, and he passed it back to me, and the water moved back and forth between us, its temperature warming, its taste changing as it mixed with his saliva and my saliva, its volume shrinking with each pass as some of it trickled down our throats and some down our chins, and when at last the first mouthful was gone, he took another and the process began again. I remember this as the most shared experience of my life. I believed I was tasting the water exactly as Pierre tasted it and that he was tasting it exactly as I did, and, more importantly, I believed I understood exactly what he was saying to me. The water was another way of saying 3th but meaning 3rd, of saying I am here with you now but meaning I will always be with you, and though I sometimes think that every cell in my body that might have been affected by that water has long since been sloughed off, I remind myself that the brain is made of cells, and I let myself believe that those few sips of water did indeed change me forever. Not just mentally, I mean, but physically. In an era when the term “bodily fluids” carried a mortuary whiff and virtually every physical interaction between gay men was mediated by a negotiation of risk, the water Pierre offered me was analog and antidote to the semen that, two years earlier, Mackie had shot in my ass with no regard for my safety, or his own. I’m not sure if this story is phrased as an answer or just another question. I do know I would like to eroticize our knowledge of the world and each other. And so, rather than conclude by writing “these words have left my mouth and entered your ear” (because they haven’t, after all, they’ve left my hand and entered your eye), I write instead: the water has left my mouth and entered yours. Now you have choices. You can spit it out, first of all, or you can swallow it. You can swallow some and pass the rest back to me. You can pass it all back to me. You can bring a third person into our chain. You can do nothing at all. There are other choices, some of which are not known to me, but, at any rate, what happens next is up to you.

About the Author

Dale Peck is the author of fourteen books in a variety of genres: the novels Night Soil, Martin and John, The Law of Enclosures, Now It’s Time to Say Goodbye, and The Garden of Lost and Found; the novel-cum-memoir What We Lost; the memoir Visions and Revisions; the children’s novels, Drift House and The Lost Cities; the young adult novel Sprout; and a collection of literary criticism, Hatchet Jobs. A former film critic for Out magazine and op-ed columnist for the New York Observer, Peck has served as the editor-in-chief of the Evergreen Review since 2017. His essays and fiction have appeared in the Atlantic, the Baffler, Harper’s, the New Republic, the New York Times, and the Threepenny Review, among many other publications. He is a co-founder of the writers collective Mischief + Mayhem, a member of PEN America and the National Book Critics Circle, and a recipient of two O. Henry Awards, one Pushcart Prize, a Stonewall Book Award, a Lambda Literary Award, and a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship. In 2024 Evergreen Books will publish his fifteenth book, Maybe It’s Art: New and Selected Criticism.

Prose

Excerpt from Marriage Marina Mariasch, translated by Ellen Jones

Torch Song of Myself Dale Peck

The House Nikki Barnhart

Excerpt from Fishflies: the Men of the Riverhouse Marream Krollos

The Chinkhoswe J.G. Jesman

Tijuana Victoria Ballesteros

Agónico Marcial, 1960 - 1994 Israel Bonilla

Excerpt from Fieldwork Vilde Fastvold, translated by Wendy H. Gabrielsen

Reflections in a Window Cástulo Aceves, translated by Michael Langdon

The Waiting Dreamer Blue Neustifter

It Being Fall Matthew Roberson

Plans for a Project Bo Huston

Poetry

As Beautiful As It Is

every woman is a perfect gorgeous angel and every man is just some guy

Big Tragedies, Little Tragedies &

A Sudden Set of Stairs &

Hyde Lake, Memphis

Cover Art

A Different Recollection Than Yours Edward Lee