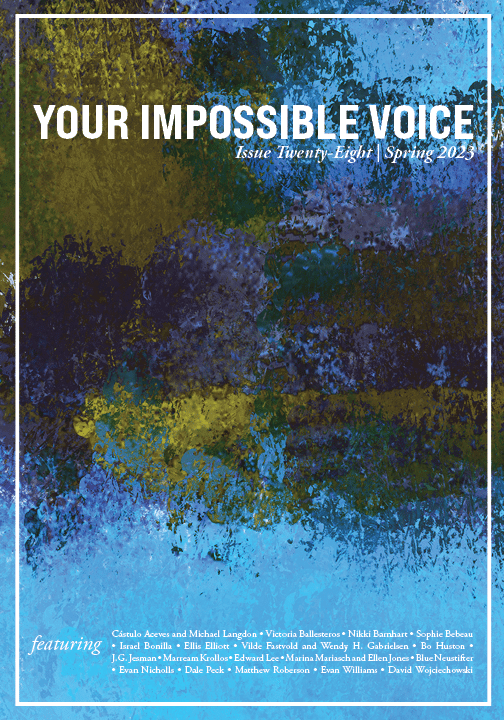

Issue 28 | Spring 2023

Excerpt from Marriage

Marina Mariasch

Translated by Ellen Jones

In relationships, everything that matters is hidden and should remain so for the benefit of all major stakeholders. Dirty laundry is a research tool that allows us to penetrate the deepest folds of the conjugal fabric. You can find it everywhere, always clinging to the couple like a second skin. It’s a reminder of how the role of women has been modified by the idea of equality.

The wife bundles up the dirty laundry and shoves it in the metal drum. A world: spinning, mixing, muddling everything. Earlier, Aryan separation: whites on one side, everything else on the other. There, in that tidal wave where everything converges, fluids meet. Dirty laundry carries memories of the day, the company, the emotions. A checked shirt is an inferno, bearing smoke and memories of everything bad, of sin. The mass grave of dirty laundry is insulting, turning what was once desirable into something hateful.

Domestic politics brings the wife to her knees, forklifting from the floor to the washing machine drum. When they are divvied up, the heavy tasks fall to her with the weight of sandbags. The left side of the bed is sinking. The springs are giving way, exhausted from their struggle against the force of gravity. They’re likely to set off an earthquake, to make the ground open up. The left side is sinking. Her exhausted breasts were transformed by the arrival of the first child. But archaic beliefs sail through the air, inspiring faith in the person running the household. The faith is strong: find out, consider, ask yourself. Find out whether it’s necessary to put a wash on, consider whether it’s a good day for it (if there are enough whites or colors to fill the drum). Ask yourself whether it’s necessary to bring in the damp clothes instead of leaving them hanging outside, if it looks like rain, or to stop the tumble dryer and remove the clothes that need ironing before they’re completely dry.

The drum spins, cradling the household’s water, that cocktail of grease and foam. Dreams spin, nightmares.

After breakfast, the house is left empty. The wife hugs the laundry basket, a lazy lover who allows herself to be manipulated. Cliques of crumbs await on the tablecloth, on the floor, laughing with that shrill laughter of small, irritating things. The ruins of breakfast move to one side to allow his majesty the tablecloth to pass, integrating himself into the bundle of damp, wrinkled creatures destined for purgatory. Confession, atonement, purification. The wash is redemptive, leaving all evil behind. The wife, still half-asleep, moves the sticky jam jar, the soft butter, the water biscuits, cracked, like her. She piles all the ingredients for an ideal scene onto a tray and removes them, putting an end to the farce of a family get-together at that time in the morning, ruined by haste, by demands, by quarrels, by the curtain of the newspaper dividing the rest of them from the husband. A different reality. Finance, foreign policy, a world outside. All of the wife’s coming and going between the table and the marble counter, changing the state of things—cold to warm, raw to cooked—isn’t enough to penetrate his space capsule. The children’s shouts and protests are background noise that competes with the traffic, the sounds of construction, of destruction. The soundtrack to married life.

The husband tries, as far as possible, to escape, pretending not to hear, participating in conversation without really being present. He steps into the street and listens to the noise of cars and machines drilling through asphalt just as people who like the countryside listen to birds when they arrive there. Evening will come around before he knows it, and the click of the door will be a political slogan rousing the blind masses. Abandon everything, run to the leader, climb him like a mountain. The boys seize him, a ball and chain on each leg. The husband is a prisoner of his own instincts. This is what procreation has amounted to, ten minutes of being tugged at, of thwarted conversations, and cajoling into bed.

The wife envies him the fresh air of exhaust pipes in the mornings, but appreciates her own routines, washing the clothes before she washes herself. Water purifies everything, the memories of the previous day extinguished in the drum, their excesses draining away in the shower.

The short-lived peace of the ephemeral morning hours is led by the purr of the washing machine. Perfumes and creams cover her body, flooding everything, depersonalizing; she is no longer herself, she has no ugly thoughts, no hate, no bitterness, she is a fragrant creature, an irresistible advert, full of dignity. The dirty laundry lies on the floor like a pile of dead animals. It stinks, a volcano spewing everything that has happened and that won’t be easily forgotten.

Bleach is her principal ally in the war against dirty laundry. It destroys everything: total whitening. Back to basics, start from scratch. Dishcloths, towels, shirts, and tablecloths are plunged into Cleopatra’s bath of white, clean-smelling milk. Stain remover is a powerful, white weapon of mass destruction. Nothing gets away from it, it kills all living particles, leaving the planet dry, mineral, humanless, lifeless. Biological traces are the manifestations of impure, evil thoughts.

Clean clothes are a mystery. In their starched and ironed folds, they guard a secret past they are determined to keep hidden. They hold a privileged status, tucked away neatly in their lodgings on shelves and in drawers. Dirty laundry cowers—it is the grime under the rug, a blot on the house. Its emanations must go unperceived by the family and especially by guests. The laundry basket, prison guard of bad behavior, loyal and obedient collaborator, provides a refuge for the disgraced. It facilitates a retreat.

Clean clothes are rehabilitated and live on, optimistic about future projects. They are not willing to talk about the past.

Underwear is a detour on dirty laundry’s route. Dirty underwear gets hard thinking about its past. It never knows who might redeem it. Its stains are the closest thing it has to a personality.

Stains, time machines that travel only to the past, evoke memories of scenes in which something was not where it ought to be. A stain is never where it ought to be, it is an eternal stowaway. It exists because of error; it is always out of place. A stain is a symbol par excellence, taking the place of something else. Catalyst of nostalgia, black hole saturated with meaning; everything comes together in a stain.

The wife wanders down the corridor in a state of undress. She stops in front of a mirror. First round. What she sees: a mountain. She too is a mountain. Of sugared milk, miles of skin, bitterness and guilt. Her most fertile flank has been occupied by a favela of social, family, and domestic demands. The wife makes countless efforts to disappear, but her volume has been increasing ever since that day she took a wrong turning.

When she was a bride: a mountain of tulle, a sugarloaf gushing down to form a pyramid. At the summit, a crown: queen of her dubious territory, crowned with suspicion in front of an enthusiastic crowd. From the base: a prostatic height, the desire to go higher. With the warmth of the home, the thaws set in, and milk gushed down the slopes as sweet, nourishing springs.

The wife is a sponge, absorbing everything, adding, piling up. The kitchen walls accumulate grease; the corners accumulate cobwebs. But then comes the redemption of soap with its sun, wildflower, and meadow-lavender-scented blessing. The wife opens a drawer full of products. Pours in laundry powder and fabric softener.

The wife leans on the washing machine. The spin cycle’s clatter massages her bones. On the tiles of the laundry room floor lie fragments of bodies, framing absences: feet, legs, torso, groin. She mentally runs through a list on which substances like milk, nicotine, affection, and acetone happily coexist. She’s gone from yellow gold to white gold. In her past there’s a bushy, peroxide mane, faded now to almost silver. Her body was built on the paradigm of the home: the house, the flat, the tower, the villa, the palace, the castle, the shed, the hut, the tent. But in that series there is no superposition, only time. Thickets of foam sprout from the drain, lustrous bouquets of heterogeneous bubbles that burst instantly, like finished dreams. The soap’s exhalations throng together, soft-skinned white lambs, the most likely victims of any predator. The wife strokes them, bidding them a final farewell, pushing her fingertips into the bubbles, dashing dreams, refreshing the present. The bubbles burst, little shocks of reality. Thoughts get tangled among the lambs’ white and grey ringlets, spiraling freely into the eye of the storm. The washing machine recovers its calm. The wife goes back to her business, tucking a rebellious lock of hair into her lazy morning knot. Second round in front of the mirror. She’d like this one to be her legacy: shoulders back, forehead high.

She crosses the minefield of discarded toys. It’s time to get her life in order. Control, design, planning. She starts sorting out the clothes. Ascending the hierarchy of practices. Accessing universality. The discarded clothes guide her actions, scattered like the daily remains of the reality she built. They reverse the breakdown in her convictions, eradicate her sense of artificiality. They award her a diploma, the status of expert.

A yellow jumper that erupts into the space, product of the anxiety and patience of a grandmother who knits, begs to be picked up. The wife grabs it and loses control of her passions. Her son’s jumper has a more irrational effect on her than her own son does. It includes desire (for an absent object); a love that penetrates. It fills the empty spaces with his absence. This effect is enjoyed briefly, then banished. The wife bundles up the jumper and flings it in the laundry basket. Her daughter’s trousers get up and walk, start dancing salsa, it looks fun, enviable, diabolic, overstepping the mark, promising something further, leaving her wanting more. The husband left his clothes on the bed. A real brute, yet he smells of dulce de leche, vanilla, tea with milk and honey. This is how pleasure begins. The wife flings herself onto the bed and loses her head among the sleeves and torsos. Before long, she loses her hands, her legs; eyes rolling, she writhes. Through closed lids, she furtively watches the peep show of forbidden parts. She does things with images. She finishes. Her swollen eyes resist the crack opening out to the rest of the day. Still, she gets up and soaks in the shower. She emerges with a smile like laundry hanging in the sun. She steps into the street and the sound of engines speeds her along. Out here, she misses the domestic paradise. She smells the cut-grass smell of fresh, promising days.

The cold dries her skin, pulling it taut. Leather boots creaking; toast, filter coffee. It’s the threshold again, the moment before, illumination, renewed hopes. The day is infinite, it overflows with possibilities. A new name, a new woman, a new skirt, a new life. Ten commandments for the working day: don’t frown, don’t make an anvil of your shoulders, don’t lose your temper, don’t judge people for their shoes, look after your loved ones. At the end of the road, the school gates. A host of femininities play at being mother, Miss Sympathy and Miss Casual Elegance. Secrets, lies. Dirty laundry should be washed with care. Dirty laundry should be washed at home. The wife advances with the bravery of clean clothes, swinging from the noose of great challenges, lying back in the hammock of accomplished goals. She vows not to lose the battle against other mothers’ eyes seeking out defects. Cutting and tailoring ideal figures. The journey is arduous, plagued with obstacles. Another triathlon of a day. The floor warps like she’s looking at it through somebody else’s glasses, turning against her. A loose tile spits up black water; the corruption begins.

At the gates, wallets rub together, teachers deliver children to the highest bidder and the children climb the mountains of their mothers in a show of gratitude for their presence, for competing, for rescuing them. Greetings proliferate, like short-lived butterflies swirling around spring bushes and then vanishing, volatile, unsustainable. From above, the mothers form the shape of a spider, taking different routes, making an effort to disguise the effort.

The wife holds her son’s hand as she walks. A connection that guarantees her transcendence, life after life. They walk towards whatever destiny might bring them. The sky is the limit, but the sky is turning to lead and collapsing in on them in fat droplets.

—❉—

My home looks over the heart of the block. There used to be gardens, a series of paddling pools. Towers rusting in the middle. But now, as of a few months ago, there is a building. It went up at siesta time with the ear-splitting sound of saws. The toc-toc of the laborers rang out, and then they slept on the esplanade so they didn’t have to travel, so they’d be there before dawn the following day. The world’s longest working days. What was left of the old building was demolished in an explosion. It only took a small pack of dynamite and then the new building went up quick as a flash, through flashes of lightning, flashes of sun through the cloud cover, between blocks of cement. One on top of another, up to the sky. Pyramids without slaves, without volunteers.

Some of the new neighbors have already hung curtains. But others haven’t, and from the living room of my house, when my lights are out and theirs are still on, I can see everything they do: when they sit down to eat, when they play with their kids, when the neighbors on the second floor get a new dog.

The people on the third floor put up nets to protect the children. They’re soft nets, white cords crisscrossed into little squares. Tennis nets. They fatten as their tensors start to wear out, just like the woman who lives there did when she was pregnant with her second baby. Her first is now a girl who waves to me from the window, behind the nets. When we pass each other in the street, though, the woman accompanied by her little girl, her ugly husband, her baby, and her 4×4, we do not greet each other.

—❉—

The wind whips my hair back. It leaves my face clear. I walk along the slope of square rocks laid out like prehistoric birds on the ground. The children’s shouts are borne along by the currents of air, running like the wind through the twisting foxtails that fill the flowerbeds lining the path, a whole pack of pearl-gray foxtails running southeast. The wind off the pampas.

As I walk, the Forest Tower leans towards me, crushing me. It has the shape of my past, the shape of a future that could have been and which now crouches on the back of my neck (my head is bowed), breaking me.

Sandal-clad mothers in red greet each other, wrinkle-free. A silver car speeds by, a white truck driven by a woman in black sunglasses whips my ponytail and the loose strands of hair escaping it into my face. Comfort. Comfort. Comfort. I find comfort alien. It is not meant for me. When I press the button in the lift, the light doesn’t come on. A girl like me gets in too. Her breathing has the rhythm of a summer afternoon in the garden, and upstairs a freshly squeezed orange juice awaits me, a bath with no one shouting, a husband anxious about becoming the kind of dad who wears his jumper tied round his shoulders, spending the weekend with her and the baby walking on a recently mown lawn, a couple of picnic baskets, wild daisies, a land of his own in the very suburbs of the suburbs. She is in the lift with me, carrying a little extra weight, carrying her maternity kilos, along with her tiny, white-gold son, on her chest.

The button lights up, I don’t have an elevator, I am not elevated. I do not have the key. She tells me: I need to ask permission. I go back down the hot rock path and ask, I’m not from here, I could, if I had wanted, have been her, almost identical to me, but licentious, with license to lie on white sands, on icing sugar, on goose feathers, Egyptian cotton and everything white, soft, and fluffy, because she studied hard and graduated early, because she looked after her son so well when he hurled himself bravely into the multicolored, tortoise-shaped ball pit. Completely fearless.

The button acknowledges my fingers’ desire and lights up. The genius of the building complex fulfills my desires. The door opens on an upper floor. The mother of my son’s friend welcomes me, fresh-faced, with cotton wool between her toes. Sorry, she says, the maid locked the door after the manicurist arrived. My son is hiding somewhere. Eventually he emerges and skips with his friend against the framed river visible through the windows with their protective nets. The friend hurls missiles at my chest while his mum half-heartedly tells him off and I say it doesn’t matter, I’m used to it.

We’re heading in the same direction. My son runs on ahead and I feel the three towers (Golf, Lake, and Forest) breathing down my neck, drawing menacingly close and saying in unison, in a voice that’s deep as a bass trio: You could have belonged here. We could have been your slaves, our machines automatically obeying your desires at the touch of your fingertips. But you are on the other side, beyond the railing. The railing that, when it sees me coming, slides elegantly to one side so I can return to my part of the world. And the colors of my T-shirt fade from too many washes, my trousers age four years and my shoes are, undoubtedly, too cheap.

—❉—

Before, the days used to all be the same. It rained during the day, then at night it was cold. People wandered around the market, myself among them, confused. The cat lost her fur but not her sly ways. She would swallow balls of fur and then regurgitate them, rippling, locked in a convulsion.

Things accumulated in the corners, signs flourished, bad omens, like a black stain or the feather of a bird whose face and origin were unknown. The underground was full, packed tight, and I could feel it all even when I closed my eyes. In the mornings, I would arrive at a place that was gray and tidy. I would bash into the edges of furniture because I hadn’t accepted the space. I would drink a powdery tea, grains collecting at the bottom of the cup, and at midday would use the scales to weigh out two hundred grams for my lunch. I didn’t have children, not even on the horizon, and I would open the door to anyone without asking their name. I wanted to be friends with the guy who delivered my dinner in the evenings, and would spend longer than necessary talking to him, but he was too polite and never crossed the threshold.

Journeys felt eternal, isolating. Sometimes someone would give me a present, but it was always something violent, sharp, and I’d end up cutting myself with it. I was expert at showing the world my vulnerability: me, with a bleeding finger. But my howls of pain or anguished face never had the desired effect.

When I got home, a letter for me had been pushed under the door. I gave myself until February, and in February we got married. We had children and taught them to read and write ourselves. In the house, nobody spoke. Total silence.

One day, I had this breakfast, an exotic breakfast from a foreign country. Strange fruit, irresistible colors, sour perhaps, bitter yet satisfying. Piles of pancakes drowned in sweet syrup, so sweet, sickly. And yet, this is what we have: unmade beds, a couple of momentary truths written on a purple notepad. The silence isn’t deaf—we are in continuous dialogue. The more distant we are, the purer it is.

For years I collected pain au chocolats so that one day I could do this: arrange them upright into walls using dulce de leche as adobe. A few gaps enhance the mystery of what might be beyond them. Finally, oblea wafers set at an angle to create the rafters. More dulce de leche on top to cover them, then sweets. Can you eat the decorations, the scenery? You can, but it won’t taste very nice. The little chocolate house lures in the orphans lost in the forest. But there’s a witch inside. I wonder when exactly I went from being Gretel to being the witch. That role always suited me, and I filled it happily, or at least without difficulty. The witch isn’t just evil, she’s also interesting. Fly, little broomstick, take me to faraway places. It only takes a single night to create little boys and girls for the cooking pot. Having children is not a virtue. Silence, on the other hand, was not achieved so quickly. It was a field of silver poplars, tall, distant, that we had to plant and then wait for them to grow. Meanwhile, the earth became waterlogged, nocturnal creatures nibbled at the chocolate, and the children didn’t get any fatter. There were times when the cows were skinny—it’s not true that hard times bring people together. In any case, the pieces holding the structure together were firmly fixed, and so the years went by. One day, they were scattered here and there, reading, in the kitchen or lying on their beds, when the whole forest started sprouting. We had built the house near a forest, but not in one, because we wanted it to be sunny. Next to the house was a cliff.

Vegetable metaphors: a tree; the branches of a tree. Two branches of the same tree. Growing together, putting down roots, sinking into the damp delicious earth, full of life, full of worms and particles in transformation. Expanding, strengthening, clawing (roots are claws) and rising. Rising, rising, moving upwards, rising to see the world from another perspective, from above. On a trunk, something solid, immobile, incorruptible, unbreakable. Two branches of the same tree that grow together but twist, each of its own accord, and subdivide into different offshoots, one getting more sun and putting out leaves. But it dries out quickly while the other, the one that has more shade, is slow to turn green, but when it does its leaves are thick, juicy. One rises, the other bends sideways.

About the Author

Marina Mariasch was born in Buenos Aires in 1973. She is currently a university professor in Argentine and Latin American Poetry as well as in Creative Writing. Mariasch hosts or has hosted radio and television programs about literature on various channels. Her poetry was collected in 2014 under the title Paz o amor (Peace or Love, Blatt y Ríos). Her stories have appeared in several anthologies and her essays have been published in volumes including ¿El futuro es feminista? (Is the Future Feminist?, Le Monde Diplomatique + Intellectual Capital, 2016). Her novels are El matrimonio (Marriage, Bajo la luna, 2011), Estamos unidas (We Are United, Mansalva, 2016), and Efectos personales (Personal Effects, Planeta Emecé, 2022). In addition to being a writer and teacher, she is a human rights activist.

About the Translator

Ellen Jones is a writer, editor, and literary translator from Spanish. Her recent and forthcoming translations include Cubanthropy by Iván de la Nuez (Seven Stories Press, 2023), The Remains by Margo Glantz (Charco Press, 2023), and Nancy by Bruno Lloret (Two Lines Press, 2021). Her monograph, Literature in Motion: Translating Multilingualism Across the Americas is published by Columbia University Press (2022). You can reach her via www.ellencjones.com.

Ellen Jones is a writer, editor, and literary translator from Spanish. Her recent and forthcoming translations include Cubanthropy by Iván de la Nuez (Seven Stories Press, 2023), The Remains by Margo Glantz (Charco Press, 2023), and Nancy by Bruno Lloret (Two Lines Press, 2021). Her monograph, Literature in Motion: Translating Multilingualism Across the Americas is published by Columbia University Press (2022). You can reach her via www.ellencjones.com.

(Photo by Brittany Ashworth)

Prose

Excerpt from Marriage Marina Mariasch, translated by Ellen Jones

Torch Song of Myself Dale Peck

The House Nikki Barnhart

Excerpt from Fishflies: the Men of the Riverhouse Marream Krollos

The Chinkhoswe J.G. Jesman

Tijuana Victoria Ballesteros

Agónico Marcial, 1960 - 1994 Israel Bonilla

Excerpt from Fieldwork Vilde Fastvold, translated by Wendy H. Gabrielsen

Reflections in a Window Cástulo Aceves, translated by Michael Langdon

The Waiting Dreamer Blue Neustifter

It Being Fall Matthew Roberson

Plans for a Project Bo Huston

Poetry

As Beautiful As It Is

every woman is a perfect gorgeous angel and every man is just some guy

Big Tragedies, Little Tragedies &

A Sudden Set of Stairs &

Hyde Lake, Memphis

Cover Art

A Different Recollection Than Yours Edward Lee