Issue 28 | Spring 2023

The Chinkhoswe

J.G. Jesman

The Boys

Chitsanzo, whose name means “example,” is very pleased with his outfit for the wedding. He has no idea who is getting married, but the local saying is that, Ants don’t need an invitation to enjoy sugar. Judging himself from the eyes of onlookers; he is a perfect score. Ten. That’s why he can’t help but unfurl a smile. Words like “cream” and “handsome” and “you’re the man” sprawl themselves on the back of his mind. On his feet are black canvas shoes, Vans. A green, oversized sweatshirt with blue sequins creates the illusion of a cosmos on his chest. Tight, yellow chinos restrict his legs to a dainty shuffle along the M1 Road to the Police Turn-Off; the affluent side of Malowena—where the wedding venue is.

Chitsanzo is only sixteen, but weightlifting has given him the upper body of a wrestler. Add to that his jutting jaw, and you have a man-looking-child whom the girls like but the elders loathe. He is handsome in a menacing way. “Anyone whose lips are the shade of an overripe banana is bound to be a hemp smoker,” his own grandmother complained to his parents. Chitsanzo drinks, yes. But he could never tolerate the smell of cigarettes in his clothes. Maybe it’s the hairstyle people judge me by, he has said, sometimes, to the full-length mirror in his bedroom. To be fair; the bird’s nest does little to plant him in anyone’s good books. But it’s more than that: it’s his attitude. “You’re an embarrassment,” his mother is quick to remind him. “Like a footballer, or a rapper. No wonder the good reverend doesn’t want you in his church.”

Chitsanzo quit school after a fight with a teacher. The police were called in. If his parents hadn’t dropped to their knees and begged pardons for their “stupid boy,” their stupid boy might’ve been sent to jail. As soon as he flunked his JCE he stopped attending school altogether. His father—a builder—took him under his wing (and continues) to teach him the trade, mixing cement and laying bricks on small projects in the township. Most, if not all, of Chitsanzo’s pay currently goes into fashion.

“Zabho-bho, aise,” his best friend Marcus says as they meet at a “T” junction off the M1.

Their fists pummel and their shoulders barge. “Easy, bro,” Chitsanzo says.

Marcus shoots a glance at his Rolex: it’s 2 p.m. The day is a scorcher. They break off the main road and stand in the shade of a pine tree on the banks of a dusty road. Sideways-hopping birds tweet-tweet! on overhead power lines.

“Yes, aise!” Marcus says, gulping. The air is so thick it could be straight out of a cellophane bag. “Tiyeni takavine.” Let’s go and dance.

Near the wedding venue, the dust-laden bodies of cars (Fortunas, Prados, X-trails, M6s, etc.) are all lined up in a disorderly manner. Like a drunken train. The boys stop by an Audi A6, 2012 model, and they take selfies, lying back on a bonnet with twisted fingers on their hands. Leavvin’ thuh lyfe! they announce on their WhatsApp statuses.

Gumbo the Guard

Gumbo stands guard at the gate. His face is stern, nostrils so flared that tiny hairs curl out of them like insect antennae. The wedding venue is fenced; brick walls enclosing a field the size of a junior football pitch. It’s brimming with people and the atmosphere is abuzz with the sounds of amapiano. On a podium, the master of ceremony—in a silver suit—bops around with jokes spilling out of his mouth. Outside, children in tattered clothes hop onto each other’s shoulders to catch a glimpse of the action.

“Chokani!” Gumbo tells them. Go away!

How different children are these days, he thinks sadly. He is old enough to remember Dr Kamuzu’s young pioneers: militarily trained, strong and helpful young men. Not these modern hoodlums with saggy pants and bandanas.

The owner of the venue, Mr. Chigayo, is strict and doesn’t tolerate “rascals” on his premises. On a wedding weekend like this, he could show up unannounced to check for “disturbances” and ensure that customers are satisfied. Any complaint of uninvited guests ruining photo backdrops means a deduction of wages for Gumbo. He cannot afford to be caught unawares—even with something as innocent as a Fanta or a plate of chicken in his hands. He must be professional at all times and keep the villagers away.

“Yes, Ankolo!” someone yells. It’s hard to know who it is with the music blaring. He clocks a couple of teenagers smacking the life out of children clamoring at the entrance. “Tachokani, mafana!”

It’s Chitsanzo and Marcus, some of the smart ones whisper (the ones who’ve been cuffed on the ear one or two times before by the older boys). One child has a football made of plastic bags (“jumbos”) in his hands. Marcus boots it over the road into the bushes. “Tachokani!”

They scram like gnats in the face of a flailing palm.

According to Gumbo, the children are a nuisance but the older boys are worse; he is forced to be friendly with them. “These kids,” he once complained to his boss. “You may think them young, sir, but they’re animals! They’d ambush the devil at the slightest provocation. It’s not like the old days when you could beat one blue without retaliation.”

Gumbo was not too far from the facts. A security guard at St Thomas Private School was recently paralyzed by students because he had ordered them to tuck in their shirts.

“Ankolo, how is it today?” Marcus says.

“Fine,” the guard responds.

Chitsanzo scrunches a five-hundred kwacha note into the guard’s trouser pocket. “Who’s getting married?”

“Yes, Uncle,” Marcus says, laughing. “Please, tell us, which fools are losing their freedom today?”

Grave as a gorilla, the security man says: “First, it’s not a wedding; it’s a Chinkhoswe. Second, I don’t know the woman, but the man is Benson Gonya, the bank manager’s son.”

“Ohoooo,” the kids harmonize.

The guard injects a little venom into his voice: “Lastly, please don’t make any trouble.”

As they proceed into the compound, a young woman in an orange and black floral chintenje dress follows. The colors remind Gumbo of a monarch butterfly. It takes a moment to realize it’s the petrol station pump girl. Her hair is usually in a bun or tucked under a baseball cap. Today it’s free-flowing. Her plain golf shirt and trousers have been replaced by a figure-hugging dress. Now, she is like Elube, that elusive woman with eyes like rice that S.R. Chitalo and the Ndirande Pitch Crooners sang about.

“Beautiful woman coming through,” one of the cheeky little boys shouts. “Beep-beep!” says another. The woman pinches her strawberry lips to the remarks. Beneath her eyebrows, cold and threatening eyes narrow. Gumbo himself has three wives. On the many occasions he has returned home drunk, all three of his wives have invariably offered him such an expression. A mix of contempt, pride, and anger. Weird that, he thinks, how women’s fury can enhance their attractiveness.

On crimson high heels, the young woman glides along past Chitsanzo and Marcus, who nudge each other and laugh while sizing up an invisible, voluptuous balloon. The woman overhears their jokes, but she has far more serious things on her mind.

DJ Fab and Emcee Chisomo

Fabrice Ndikumana, a young man from Burundi, leans against a speaker the size of a barrel. He has headphones dangling around his neck like the ears of a bloodhound. In front of him is a mixer, beside which is a Chromebook with the latest hit songs. When he played Big Flexa earlier (by Costa Titch) the crowd went berserk. Their screams and stomps alone could have moved a seismogram.

When the District Health Officer of Malowena Hospital warned Fabrice about the dangers of loud music, Fabrice said: “What?” The doctor was about to repeat himself when he realized Fabrice was only joking. As a professional disc jockey, the young man had long decided it was better to be tone-deaf and rich than poor but full of good hearing.

Fab (as his friends call him) is Burundian. Ten years ago, his widowed father fell in love with a Malawian businesswoman in Bujumbura. They eloped, and now they run a hardware store in town.

Fab has been fascinated with musical instruments since childhood. He learned guitar from his father and taught himself to read music through a MIDI keyboard. In his teens, he founded a recording studio that provided jingles for businesses in the region. His best friend, Chisomo, suggested they work together as a DJ and emcee. Like The Fresh Prince and Jazzy Jeff. They now dominate the wedding entertainment market.

“Achinkhoswe achimuna, please step forward,” Chisomo announces.

Fabrice—in a colorful dashiki—watches his friend keenly, waiting for musical segues.

A gray-haired man in a faded suit—uncle and marriage counselor of the fiancé-to-be—steps onto the stage with a live chicken in his hands.

“Our rooster has been missing,” he addresses the audience in a pantomime voice, his eyes latched onto the mother and father of the fiancée-to-be. “We heard it’s been wandering off into your chicken coop—with one of your hens. Is it true?”

There are cheers and whistles in the crowd.

The mother of the fiancée-to-be clears her throat. “Ah-ha! Our coop is of a humble size, but it sure does have some beautiful hens. Let us see what they’ve been up to.”

Behind her are three women, their heads veiled in a beautiful chitenje.

“Hmm-hmm,” the uncle says. “Perhaps our rooster can point out who he’s been visiting. The one who has caught his eye.”

The fiancé-to-be unveils the first woman.

“Is this her?” the emcee jumps in, exultantly.

Like a sculptor considering all angles, the fiancé-to-be folds his hands over his chest in contemplation, only to offer a hard “No!”—much to the amusement of the audience.

On to the second woman: “Is she the one?” Again, the fiancé-to-be shakes his head like a dog ridding itself of water.

Judging by the number of people in attendance (well over a hundred), the uninformed could easily mistake a Chinkhoswe for a wedding. It isn’t. It’s a proposal. A public announcement of the couple’s intention to marry. And a chance for their families to bond.

The fiancé-to-be draws the chitenje off the head of the last woman standing, and declares: “This is the one!” There is ululation as he gets on one knee to slide a ring around his fiancée’s finger. “I love you, Benson,” she says. “I love you, too, Margret,” he replies.

To mark the happy occasion, DJ Fab plays the “Buga” by Kizz Daniel. Go, low, low, they all sing. Go, low, low! Buga won!

“Benson had no real interest in Dorica. He had just come out of a relationship and she happened to plug the holes in his heart.”

Benson and Margret

Benson swells out his tuxedo like it was made of spandex. It’s not his “looks” but his sense of “umunthu,” or humaneness, that’s most appealing. He is charming. And considerate. Whenever there is a funeral in Malowena, you see him shadowing one of the organizers, rolling up his sleeves to dig graves or assume the position of pallbearer. It is the reason the proposal is attended by so many people. In Malawi, those who shy away from the community become pariahs.

Margret is beaming with joy, but she covers her mouth with her hand as though smiling were against the rules of modesty. Her naturally thick eyebrows have been trimmed to a fine line; her eyelashes made long and curling like those of a secretary bird; all of this in praise of her honey-colored eyes that leave Benson awash with love.

“Parents of the fiancé! Parents of the fiancé!” announces the emcee. “Mommy and Daddy. Can we please get a word from Mum and Dad?”

“Ladies and gentlemen!” Benson’s father begins. His tone is about as formal as one would expect from a bank manager. “Today, my wife Gladys and I have been made very proud of our lastborn. To settle down at twenty-six, with a beautiful and polite hen like this—” he points at Margret—“is quite, uh … Well; it’s not an embarrassment to us.”

The real hen—now in the hands of Mrs. Gonya, his wife—flaps its wings in a comical manner. The emcee is quick to capitalize: “Daddy, you have left out one quality as we can all see … This is a woman of high energy!”

Some of the “experienced” couples in the audience giggle at the innuendo. Margret averts her eyes to the sky. Benson sticks his chest out like Superman, his arms akimbo. And soon enough the entire crowd is in fits of laughter. But while in the throes of comedy, Benson notices a familiar—and yet unsmiling—face in the audience. It’s a woman. In an orange and black dress. Dorica. That name and all that it carries weighs heavily on his mind.

Benson is the manager of a lodge. He met Margret on one of his frequent bank visits to deposit his place of work’s earnings. She asked to go ahead of him on the cue. He didn’t mind; she was beautiful.

“You mean to say you don’t know her?!” his friend the cashier said with his jaw hanging. “She is in hospitality. Works at Mphamvu Lodge.” He winked conspiratorially and remarked on how well-behaved she was.

The next day, Benson went to Margret’s workplace pretending to be a customer. She remembered him and greeted him kindly. “How much are your rooms?” he said—as if he could afford them. Fifteen thousand? He pretended the figure was too low and meandered the lodge corridors beside her, commenting on the state of the showers (“Smallish”), the beds (“Could be bigger”), the garden (“No parasols?”), until he had to admit: “I don’t care about the rooms. And I don’t really have money. I’m just here because you are so-so nice.” From these humble beginnings a whirlwind romance took flight. Within weeks their families were introduced. “She’s the one,” Benson told his friends. Forgetting there was another one. Dorica. Standing before him now like a revenant.

With his innards in a knot, Benson turns his back on Dorica in order to face Margret, her parents, and the emcee. It takes a while for him to hear the applause and realize that someone has just wrapped up their speech.

A girl in a blue pattern chitenje dress (similar to that of the bride) ambles onto the stage with a grilled chicken on a plate. (It’s not the rooster or the hen, but their unlucky cousin—a martyr whose mission was to symbolize “family union.”) By devouring its meat together, the families promise to digest any future squabbles or hardships, together. As Benson is about to chew on a succulent breast, “the other woman” storms onto the stage.

“You gigolo,” she yells. “Tell these people what you have done. Tell them …”

Everything happens so fast that it plays out in slow motion.

Benson’s face scrunches up.

The crowd lets out a massive gasp, like sports fans watching a terrible foul.

The father of the bride grabs his heart in shock.

DJ Fab—who knows all about Dorica, being close friends with Benson—leaps onto the stage.

There are murmurs, cheers, and boos as the woman pleads: “Tell them I’m carrying your child! Tell them how y—”

“Ladies and gentlemen,” the emcee interrupts. He, too, knows who Dorica is, but he plays ignorant for the sake of Benson. “Ladies and gentlemen, this is why us entertainers need health insurance. Someone please take this mad woman away.” A few people giggle, but most are confused. To cut through the chaos, emcee Chisomo orders one of the DJs on standby to play a song. With the bass thumping, Chisomo initiates the process of perekani-perekani, where people drop money into a wicker basket for the newly engaged to plan their wedding.

Margret is furious. She knows of Dorica, but this is the first time they have ever met.

“There’s a girl at the petrol station who’s obsessed with me,” Benson told her. “I only dated her for a week, but she made up this fantasy that I planted my seed in her.” When Margret gave him a stare that said Did you?, he shrugged.

A teary-eyed Margret then sought her mother’s advice. “My daughter, if someone tried to steal your handbag, wouldn’t you fight for it? Why should it be any different with the man you love?”

That advice is the reason Margret gives Benson’s hand a squeeze. “This is my husband,” her gesture is saying. “And no one can take him away.”

With the apathetic swiftness of a SWAT team, DJ Fabrice and Gumbo drag Dorica out and off the premises.

Dorica/Nandi

Life is hard. The proverb says: If the first sound we make in life is a cry, it’s not surprising our last one is a sigh. The indignity that Dorica suffers leaves her speechless. She is manhandled—there is no other way of putting it. Benson. Gumbo. Fabrice. Chisomo. All of them dispose of her as easily as the wind blows away a stink. Her mind becomes clouded with hatred and fury—and then, shame. What has happened is not just a denial of speech or motherhood or pregnancy; it is a tribal ousting, which leaves her shaken to the core, and very confused. What did she expect? What was she trying to achieve? Benson already told her he would never accept the child. Nor would his family. Curse them all.

Two months ago, when Benson called Dorica “Nandi” at the petrol station, she thought he had said “nthambi,” meaning “branch.” He was trying to compliment her beauty, in that she looked like the actress who played the mother of Shaka Zulu in the 1986 TV series. When her girlish eyes grew wider, he explained that the warrior king and his people were in fact ancestors to the tribes in Malowena: the Ngonis. Dorica bit her lower lip, not knowing what to say.

She helped him fill up a five-liter jerry can for his workplace’s generator. He tried to impress her with his knowledge of films. (Hollywood is the best. Nollywood has too much drama and Bollywood is getting better.) When he asked if she liked movies, she nodded. What kind? Any. That weekend they watched Henry Cele play Shaka. One thing led to another, soon enough she was answering to the name of Nandi.

Benson had no real interest in Dorica. He had just come out of a relationship and she happened to plug the holes in his heart. When she told him she was pregnant and that she would keep the baby, he said, “It’s not my business.” When he met Margret—the woman of his dreams—the nightmare of Dorica was relegated to the back of his mind. Dorica would never abort the baby. Her mother said there is no such thing as an illegitimate child because there are no laws against life, and even if there were, God is allowed to break them.

Although Benson had blocked her number, Dorica knew about the engagement. The thought of her raising a child alone caused her great distress. She also felt guilty, for her unilateral decision to bring life into a whirl of dysfunction. One evening a stray followed her home. The way it kept coming despite her best attempts to chase it away; would her child do the same for its father’s affection? What kind of life would that be? There had to be a way for all parties to accept the situation. “For the sake of the child,” she rehearsed before crashing the wedding. “Everyone should know the truth; for the sake of the child.”

Now, reeling back from being shoved out of the wedding venue gate, Dorica’s shame, guilt, and anger take surprisingly little time to dissolve back into her old quest for truth.

“Don’t come back here, madam,” Gumbo says in a voice that lacks authority.

DJ Fab tells her to “Go home and do the right thing.” Whatever that is.

Dorica doesn’t cry. She doesn’t fight back. She straightens the creases off of her dress and walks away. The closer she gets to her home, the clearer the solution to her problem becomes: a paternity test.

Marcus

Beside a Greco-inspired cement cherub, Marcus stands, stuffing his mouth with samosas. On his face are non-prescription reading glasses through which an array of Bain Marie pots shimmer. They are filled with food. He looks like a food scientist assessing flavors. Why shouldn’t he enjoy himself? Didn’t Chitsanzo pay five-hundred kwacha to the guard? There is chicken kwasu-kwasu, goat meat as soft as bread, oil-dense mandasi, rice and peas, nsima, and behind them is a multi-colored pin rack of soft drinks. Marcus can hear the hubbub behind him, but the piri-piri flavor kissing the roof of his mouth stops him from looking back. Even the chefs are distracted by the commotion, their mouths open like dead fish.

“What happened?” one guy says.

“It’s the girl from the Fuelco petrol station,” says another. “You know her, Dorica?”

“Dorica-Dorica-Dorica… Ahh! Yes. Not good.”

“She claims Benson has left his child inside her.”

A man shakes his head. “Is that a reason to wreck a perfectly fine proposal?”

“No. But she’s the type, isn’t she?”

Silence.

“I’ve seen it with my own eyes,” the same guy persists. “It’s all online: mistresses scheming, loose women flinging their underwear at the faces of devilish pastors—anything is possible these days.”

“In my father’s time, a bastard was rarely kept,” says the other. “Weeds ought to be plucked before they can flourish.”

Marcus—who is now getting seconds, chews so angrily that he bites the inside of his lip. The careless words lacerate his spirit. When his mother died of meningitis, his father dropped him off at his grandparents’ house and never returned. His gogo’s are good people, and they love him, but Marcus can’t shake off the notion of not being wanted. It’s the reason the word “bastard” has stung him. Mind your own business, he wants to say. Women can do what they want with their own bodies. But he knows that these men would sooner laugh or beat him up than take notes. Should he say something and risk banishment from the venue? He is not sure.

“Young boy,” a stoic man in a white coat and toque says to Marcus. “Please don’t hold up the line.”

Marcus squirts tomato sauce over his rice, then heads to an empty chair.

5:15 p.m. is the time on his Rolex. His plate is empty and his stomach is full. Chitsanzo is in the distance, cutting a rug. As the sun dives into the horizon, leaving a splash of fuchsia in the air, music washes over the crowd with a gleeful amnesia. They cheer as though the pain of the pregnant woman who had caused a stir earlier was nothing but a nuisance. A fly on a windscreen. “So what if she has a problem?” one woman said. “We all have problems! That’s why we’re all here; to enjoy this, aren’t we?”

About the Author

J.G. Jesman is a British-Malawian author and animator. His debut novel, Chisoni, was published by Penguin Random House South Africa in May 2022. His short stories have appeared on Fairlight Books’ featured short stories, The Interpreter’s House, Water~Stone Review, and elsewhere. He has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. He is currently working on a collection.

J.G. Jesman is a British-Malawian author and animator. His debut novel, Chisoni, was published by Penguin Random House South Africa in May 2022. His short stories have appeared on Fairlight Books’ featured short stories, The Interpreter’s House, Water~Stone Review, and elsewhere. He has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. He is currently working on a collection.

Prose

Excerpt from Marriage Marina Mariasch, translated by Ellen Jones

Torch Song of Myself Dale Peck

The House Nikki Barnhart

Excerpt from Fishflies: the Men of the Riverhouse Marream Krollos

The Chinkhoswe J.G. Jesman

Tijuana Victoria Ballesteros

Agónico Marcial, 1960 - 1994 Israel Bonilla

Excerpt from Fieldwork Vilde Fastvold, translated by Wendy H. Gabrielsen

Reflections in a Window Cástulo Aceves, translated by Michael Langdon

The Waiting Dreamer Blue Neustifter

It Being Fall Matthew Roberson

Plans for a Project Bo Huston

Poetry

As Beautiful As It Is

every woman is a perfect gorgeous angel and every man is just some guy

Big Tragedies, Little Tragedies &

A Sudden Set of Stairs &

Hyde Lake, Memphis

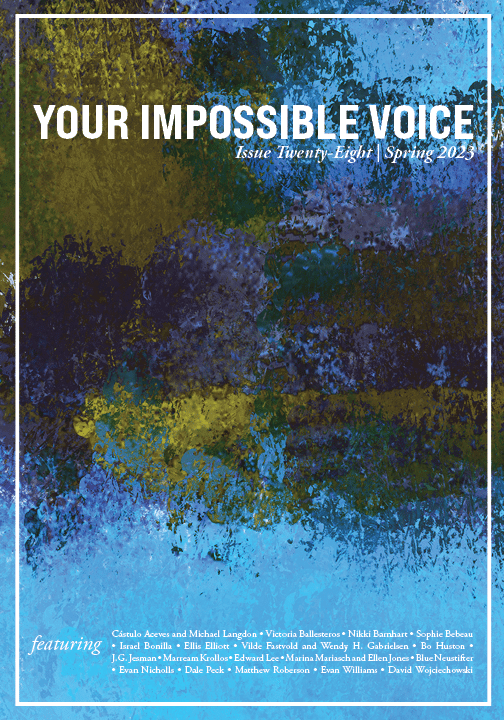

Cover Art

A Different Recollection Than Yours Edward Lee