Issue 28 | Spring 2023

Agónico Marcial 1960 – 1994

Israel Bonilla

He longs to tell someone all that is haunting him now in the darkness and agitating his soul, but there is no one to tell.” Thus, Chekhov captured in Danilka a state that is natural to a few spirits who seem destined for a short stay. When they manage the articulation of this disquiet through aesthetic form, there is a commotion in our inheritance. Agónico can be firmly placed in this company. But it should be said at once that he was not as steady in the crystallization of his talents as a Lucan or a Shelley. He shared more with the superbly diffuse Leopardi, even if no direct influence can be traced—a symmetry all the richer. On the surface, there are five poetry volumes of irregular merit; underneath, approximately three thousand pages of letters, essays, and notes. Weaving work and circumstance is here a congenial task.

Agónico’s childhood belongs to myth, and it is now irretrievable. We know with confidence that he was born in Visalia. All other information has been gleaned from his letters to Segura. In them, Agónico talks of his father as an exceptional autodidact but never consents to tarnish his image with the mundane. Of his mother, he says only that she died before he was one year old. This lack of details affords him the flexibility to indulge in make-believe:

Were I certain of a long, fulfilling life, I would write a monument to my father: perhaps six volumes could contain the memories I gathered during our thirteen years together. Not one of them trivial, for he was careful to give time a varying weight. It is easy to detect what is foreign to those who are closest, yet I cannot recall anything ever being so to him. The world as I understand it materialized from his breath. I owe him my two greatest loves: Burns and Othón. He read poetry, but he was not as weak as us, Segura. He knew it is better to live it thereafter! Do not ask for something as vulgar as proof. Everything of import he modeled in his soul. I ignore its whereabouts.

He refused to specify more about their relationship; instead, he increasingly made of him a quasi-religious sage. There are two other letters in which he speaks of his childhood with a tone closer to intimacy. The first lapse comes embedded in an answer to Segura’s highly rhapsodic view of innocence:

Did Baudelaire really think that through? Children always strike me as foolish. Clever little machines, at most. Adults willingly grant a poetic tinge to their improvisations. Have you considered, however, the frequency with which we tune them out? Oh, yes, yes, I know more than one genius who CREATES so so so so much that he eventually stumbles upon something valuable, but let us be serious: most die before that happens. (Permutations are cruel.) The child and the childlike genius are both the prey of chance. I associate genius (lone, spare) with conscious, miraculous control. When I was seven or eight, I was addicted to limericks. I filled notebook after notebook. For years, I believed them the groundwork of my vocation. You know, kind of like Goethe. Then I went back: dinosaurs, trees, farts, pirates, cookies, planets, wands, dogs. Prosody made no difference. The child does not prefigure the poet. I find it is the other way around.

The second lapse occurs after Segura shares a meaningful, almost mystical experience:

I concede the beauty of what you have recounted, but I will withhold my assent. However precocious, children are not religious. The coat of transcendent meaning was laid down in subsequent recollections. Children are the foremost slaves of sense. Maybe that’s their real advantage over us. For example, I remember running alone in the park as twilight approached. Suddenly, I heard other footsteps. I ran home. They grew louder. It was only when I arrived that the footsteps ceased. Was it my doppelgänger? Was my presiding spirit getting lazy? If I avoid these thrilling hypotheses, I can distinctly recall that I already felt uneasy about the encroaching darkness. An alert kid is an unhinged kid.

Agónico, then, seemed to enjoy writing and solitude very early on. Now, one must understand that his refusal to romanticize childhood is part of the myth. He always insisted on a sudden awakening of his inner life, and the significance of this awakening required a flat rejection of previous light. They who would deny the child a different modality of experience cut themselves off from their bedrock; self-understanding becomes self-justification.

There is no information about his schooling. Tutoring would be a reasonable inference if he were taken at his word. Yet most of his education can be explained through other means: his frequent reunions with a group of self-styled poètes maudits in the late seventies accounts for the orientation of his first two pamphlets and for hundreds of prevailing references. To bridge the gap between his childhood loneliness and these unorthodox friendships, Agónico had his aforementioned awakening at hand:

I drifted in violent boredom. Petty crime looked okay. I got involved with a couple of brothers who robbed a long list of shopkeepers. Some were fatalists, others were bootstrappers. So I had to go against my instinctive physical cowardice, since the latter were no believers in the police. It was a losing battle, but the city has its blessings. As I was walking to meet my accomplices, a preposterous fifty-year-old man handed me a brochure. He was wearing a shabby yellow suit, a black beret, and green plastic sandals. Can you fathom he was my Hermes? I still can’t. One page was filled with a long, obscene poem about group sex with the departed (amusing). Another had a worthless exquisite corpse (are they ever not?). The last had Othón’s “The Mendicant.” Have you read it? “Was he rich? … Today faith is his lone gem, / and for royal scepter he has left / the sullied cane on which he leans!” Then and there my sleepwalking came to an abrupt end. I was familiar with Othón. My father had given me an anthology of his verse, but that which will dictate our fate tarries to live.

In the same brochure he found an address for a bar. Soon he met Les faux élus.

At last, the tyranny of Agónico’s voice is overthrown. The accounts proliferate: characters in novels and short stories, glimpses in poems and essays. Les faux élus comprises a dozen graphomaniacs. Nevertheless, Eulalio Eleodor, the Methuselah, wrote in his Brief Tour through a Long Mistake the most well-known and fascinating portrait:

Little Rombo was constitutionally incapable of consenting to irony. He had the demeanor of someone who had omitted a word from our name. So? So we all took turns pranking him, and we all took turns fighting him too, for that was his gift to us! We were desperately in need of a short-tempered, self-deluded poeta. He didn’t write, he didn’t read, he didn’t talk. He was there to raise hell, and he was also there to convince us of his heaven-ordained trances. The weeping willow mane and ragged clothes were meticulously chosen for aid. We went along with suppressed laughter. I tell you, then, that it was a tragedy for our Verlaine to devolve into a Notarlaine! They conferred and what do you know … Little Rombo has a pamphlet! I refuse to imply, for risk of imploding, so outright I say it was a collaboration. Little Rombo produced only one good piece of work … unknown proportion notwithstanding. To all antiquarians who heed me: beware of self-proclaimed genius. It must be a mystery to itself!

It is an unexpected caricature, yet it reveals that Agónico was quick to embrace his call, regardless of youthful affectation. Too much, unfortunately, has been made of the divertimento. Gerardo Viter, though a close friend, certainly did not co-write Ballads for the Brawl. Moreover, during these supposedly barren years (1978-1982), Agónico was working on Binds, a series of vignettes on conventions. Although the poetry was still far-off, there were hints of its tenor:

Light through the foliage checkers their path. Hand in hand, erect, they roar with laughter, press against each other. Behind, arm in arm, resolute, they display a vigorous smile, face forward in strange discipline. Shade through the foliage checkers their path.

In the festal hour, he chants and is applauded, body slack for the atavistic dance. Stagger: bow. Slur: grin. Rogue. In the intimate hour, he murmurs and is passed by, body undone for the fresh spasm. Stagger: slump. Slur: sleep. Clown.

Tentative forays into his assailing of continuities. The exercise was strenuous: restaurant gatherings, dancing, small talk, tipping, uniforms, directed teamwork, chain of command, salary. As a waiter, he kept the list renewed.

The années maudits, as he called them, would turn out to be unique in two respects: work and companionship. He would never again hold a steady job, and neither would he maintain regular contact with a group. There is a partial explanation in a letter to Segura:

It was necessary. I needed familiarity with the world of hierarchy and the world of equals. There was only one lesson, to be sure: the soul needs an indefinite retreat after a single plunge into the alien stream. I can anticipate your protest! You still assist readings and institutional banquets, don’t you? You still play the groveling role that Goethe took pains to exalt with his lifelong example. Let me strike immediately, now that recollections cluster about. My fellow workers were nothing but accidental outcasts who cowered at the sight of authority’s symbols. They could barely muster discontent behind its back, lest betrayal possess a precarious colleague. So it was safer to baptize a whipping boy. My fellow poets were much the same. The difference that causes great obfuscation is that they are better at articulating their case. With them, it is not a matter of whipping boys, you see. It is a matter of taste! As you may imagine, intrigue has never quite struck me as a dignified phase of humanity. I applaud your guile, for that is the sole faculty I suppose would overdevelop. Le meilleur, c’est un sommeil bien ivre, sur la grève.

The prideful tone does not conceal the bitterness. All who mix with the world at large and face it head-on are certain of their worth, however unconsciously; the accretion of ordeals is a source of cohesion. But those who heap scorn on the world are creatures of supreme vanity, easily wounded; they wish others sensitive to their merits by mere presence. If we remember Eleodor’s words, Agónico was the brunt of many jokes. Humor grows inversely proportional to self-delusions. Humor is the gift of clearness. And spirits of a romantic cast always flock to the mist.

Ballads for the Brawl, Agónico’s first poetry pamphlet, is the outcome of this essay in adjustment. A troubled sense of brotherhood haunts the celebratory tone of its fifteen pages. Yet the effect is not deliberate. Agónico pines for the heights of Burns’ “The Jolly Beggars” and Othón’s “Canto del regreso.” His unwillingness to confront his distaste for companionship, however, precludes the spread of passion. As happens with budding poets, there is only a clearing of the throat, even if chance offers the odd touch of candor:

Here’s a pint and a pal,

a smoke and a golden braid.

We drink not to forget.

We drink purely as aid.

There’s the bar and its castoffs,

none so willing to break.

We drink not to demur.

We drink purely to fake.

Here’s a shot and a stranger,

a pipe and an auburn tress.

We drink not to give out.

We drink purely as guess.

Third-rate Burns, ultimately. The imagery is conventional and the rhythm too monotonous. Agónico himself would later on dismiss the collection:

I did not feel suited for rhyme, but it became a necessary crutch. There was something about its arbitrariness that saved me from the extravagance of half-formed expressions. Though “saved” is a suspicious word. Now that I read the poems, I confess to a profound revulsion. Where do my influences end? Where do I begin? These are ever-present questions, I know. In this particular instance, you must agree that I merely composed sad hypotheticals: “What would Burns write about this place, about this crowd, about this moment?” I fear thirty existing copies are thirty too many. May obliviousness bless them with oblivion.

He would publish a second collection four years later. During the interval, he worked again at prose. Without Helm proceeds, similar to its predecessor, through vignettes. But Agónico now shows signs of artistic improvement. Every vignette is a symbolic instant in the life of Termal, a stand-in for the author. The work demands an attentive double-reading of its constituent pieces: one reading reveals Termal’s individual struggle (the poet’s will against the world’s resistance); the other, humanity’s struggle to open itself to a half-devised set of new values. Since Agónico left no commentary regarding its completion, attention has clustered around it to a remarkable degree. Only There—night, arguably his greatest effort, has invited more exegesis. A particularly baffling “instant” illustrates the cryptic style:

The mute wall deceived me into beliefs about its imperviousness. There was a lineage of deception that had extended to this moment. Lineages come to an end, and it was my distinct prerogative to deliver the blow in an unheard-of cadence. Tender blow, as became the last. In notes, in melodies, in song. In raw prayer, distilled to fit the dearth. It lived. I made it my attendant.

Agónico moved about and worked odd jobs in short bursts (elevator operator, street stenciler, newsie). He finally published Flicker and a Half-Illumined Face (1986) through Malagüero, an independent press that folded after its seventh title. This collection of twenty short poems marks an advance over Ballads, yet the strictures of verse make it inferior to Without Helm. Agónico cannot marry sound and sense. Ballads tried for the first; Flicker, for the second. But it must be admitted that he has a better handle on compression:

It was whispered that we languish

for cares too mild, insular and firm.

I respond with my devotion

to a narrow flame.

Although the work itself is of no great import, it emboldened Agónico to contact Sebastián Segura, the “Mexican Diderot”—a life-altering event. Their correspondence spans over a thousand pages and it gave Agónico a chance to put forth and defend his developing views. The exchanges are fundamentally intellectual: Agónico dislikes confession; Segura relishes theory. Both are energetic and opinionated. The only perceivable asymmetry is scope. Segura is an obsessive reader, whereas Agónico never outgrew his superstitions about influence. From the outset, the pattern was established:

I read Poetry, the Pillager’s Art with care and bewilderment. It has been years since I felt so involved in the convolutions of a book. … You have constructed a fear- inducing monument to Influence. Your ideas stand sharply in contrast to mine, and it is out of admiration for their vibrancy that I would be interested in knowing more about them. I send you my morose pamphlet as a sort of catalyst. It is mercifully brief. Grant me the privilege of foolishness. I am young.

Segura’s letter arrived swiftly:

Only a certain type would find my book “a fear-inducing monument to Influence.” This type would readily publish Flicker—a froward and impatient bundle of oracles. I can hear the message through the din of its meter: “Is not the unrepeatable misery of our conditions life-giving to the poet? Is immersion not a task that will forge a new spirit? Is it not time to forfeit the cracking tools?” To which I answer, my would-be friend: the tools crack only under preternatural force, and this only to a minimal extent; it will be long before they are tested to their limit; it will be long before the poet can drop them and claim his inheritance. Inés used them, Blake used them, Hölderlin used them—all three possessed by a vision of the ascendancy. Do not rush yet. Ruminate, have a look at the capstones, sketch. You are young.

Now that Agónico knew there was a sympathetic ear, he did not loiter. He was also compelled to resist Segura’s conceptions systematically. In less than a year, Agónico wrote Scattered and Still, the true parallel to Without Helm. The range is eccentrically wide. There is a poem on bottles:

The clankclamor of glass coils round

brittle limbs, tender with memories

of haunts, lost amid ethanol

and the merciless second:

alarm that seethes the spirit, premature.

There is a poem on sprinklers:

Still in the open, it welcomes

the thirst, the grime, the ease,

a crowd that stomps its aim.

Trickle of encircling glut.

Then there is a poem on tattered propaganda:

Ritual hope in grounds always void

of something or other, the slick face

eventually jeers.

Less a symbol,

more a wallpaper that lulls the gaze

to lassitude. Only sleep is willed.

But Agónico maintains, at last, unity through tone. One is willing to listen, however quaint the derailment. His voice has grown steadfast and saturnine. It reaches silence before transforming into a rant. This precludes, naturally, instants of elevation: Agónico seems closer to the Augustans than to the decadents in most of their guises. Burns and Othón have ceased to exert an open influence, and thus they can now lodge in greater depths.

Scattered and Still (1987) was published by Alabaster, the fledgling press of one of Segura’s friends. Fifteen of its fifty printings were sold. Somewhat intoxicated by this sustained effort, Agónico envisioned an ambitious new work:

We have inherited from pure poetry the comforts of brevity, we have been much too at home in the certainties of Poe. The incandescent lyric captures the fleeting mirages of mind, no doubt. But what about the ravages without? I spend my nights awake. Time seems then prodigal in accommodating events. Whatever it is they share can be captured only through a languorous form, one that suggests the wakefulness of years. Enough of the instant. I call forth the epoch.

The purpose is inchoate, and Agónico never actually managed to be anything other than vague about it. This has been offered as a reason for his sudden abandonment of the work.

There—night displays every resource available to Agónico as a poet. The unfinished poem is concerned with a long series of interlocked incidents that obtrude upon a walk across Visalia’s poorer neighborhoods. Agónico renders identity through meter and evokes the flow of time through themes. He is at his most rabidly obscure, and yet the oscillating emotional tones are impactful. A well-known passage affords a summation of its merits:

They flock, the young.

Violent through sheer

excess. Of what

use the ferment?

Washed-out glitter,

sprawl of smoke.

A candid call

to lead constricts

each chest and steers

the tread of death.

And its tender echo—recurrence.

In the extended arm about to burst.

In the protruding half about to fall.

In the visitations of the alley,

where cocks consort and nipples are nibbled.

This passage, moreover, reveals the faded presence of the walker. He is embodied insofar as he moves and sees, but nothing relates to him, nothing touches him. Agónico explained the choice to Segura:

Again I refuse the fruits of pure poetry! The stamp of individual emotion is an obstacle to enlargement. If there is to be an I, it should be as thin as the sign. A universe is born through its surreptitious manners. The I is something of a ghost and something of a thief!

Segura, in any case, was ambivalent:

Are you fully conscious of the likely outcome? The rambles of your hazy eye will coalesce in their exteriority. They will be as suggestive as stained glass. But so long as you refuse “individual emotion,” you will not reach the depths. It is curious to see this documentary strain in you. For all your iconoclastic talk, I sense a wonderful coordination with the times. Perhaps poetry’s willful misstep is the authentic source of your irritation. Are you an aligner?

Agónico and Segura were always in playful conflict, but the nature of this work eroded Agónico’s zest. As Hazlitt states, originality is “feeling the ground sufficiently firm under one’s feet to be able to go alone,” an unfamiliar feeling for Agónico. At this point, his correspondence with Segura became erratic.

Agónico’s years of toil (1988-1994) were beset by doubts. He no longer took for granted what he had called his vocation:

I throw my dirty notebook into a corner and scribble and scrawl. Why is this so undignified? The painter has his studio and wastes away surrounded by his creations. He never betrays his tools, he never exchanges. The dancer has the assurance of blood and a testifying body. He is known (or at least intuited) wherever he goes, he will not be confused with the accountant or the banker. What do we have? What do I have? An abstract kingdom that I enter in the most abject and humbled manner. That I enter, ultimately, on stolen time. I have been shrill about my freedom perhaps because there is none. The poet is above all a parasite. He is not self-sustaining. He must first be x, then he is a poet.

There were, regardless, two sources of relief throughout: the “correspondence” with Ventura and the sporadic work on The Last Ebbing Sands, an ominous memoir.

The letters addressed to Ventura (1992-1993), fifteen in all, remain an oddity. It seems Agónico did not send them. They have an uncharacteristic tone that borders on mysticism. Given the absolute lack of information on the addressee, some critics have speculated that the whole affair is purely a literary exercise—some have even suggested that it points to a new period in his work. The tenth letter is representative:

Frail-winged Ventura,

I am accustomed to penury in several of its garbs. You must be able to tell by my crumbling frame. There are spasms inherited from hunger, marks inherited from force, creases inherited from light, and a wheeze inherited from cold. It is nothing. Not so the spiritual penury to which I am subjected in your presence, for I know that in your reserve lies an unbounded desire that would, mercifully, transport and annihilate us. Is that not what we most need? A taste of frenzy and then au revoir. Help us, rend the morose cocoon of vacillation that so fixes you to the sordid demands of the minute. We will not require time. The proof is in my captivity. I am held by our night at the bench, smoking without a word passed between us, your uncovered thigh receptive to a brush of my fingers. Si j’ai du goût, ce n’est guères que pour la terre et les pierres et tois.

Indeed, the letters concern themselves ardently with death, and The Last Ebbing Sands (1993-1994) is a memoir of farewells. But it is doubtful whether these writings constitute a new period. They are far too intimate and oblique. The cynic who lurks in the spleen of every scholar insists on the writer’s nonstop performance for posterity. But should it not be asked whether a yearning monad lies behind the elaborate manifestations of spirit? Should it not be asked whether its effusions connect it to an unmapped recess? The poet is supremely the poet when he shapes his expression. The poet is the poet even while he drinks his coffee and kisses his lover. But is he still a poet when adrift and shrouded? Is he not then simplified? Elemental?

Agónico renounced There—night after one hundred and fifty pages. His closing months were occupied with The Dregs They Gather (1994), a collection commissioned by Segura for Alabaster, now a respectable independent press. It is an inadequate volume, more of a scrapbook, but it brought the only recognition Agónico ever received.

His body was found a November morning in one of the streets he distilled for the gaze of posterity. He was victim of an armed robbery. Time is zealous with the names of its devoted children. It will blot out the ignoble fact. Agónico will have died of neglect and joined the martyrs who never quite impart their lesson.

About the Author

Israel A. Bonilla lives in Guadalajara, Jalisco. His work has appeared in Able Muse, Firmament, Exacting Clam, Berfrois, Minor Literature[s], King Ludd’s Rag, Maximus, and elsewhere. His debut micro-chapbook, Landscapes, is part of Ghost City Press’s 2021 Summer Series.

Israel A. Bonilla lives in Guadalajara, Jalisco. His work has appeared in Able Muse, Firmament, Exacting Clam, Berfrois, Minor Literature[s], King Ludd’s Rag, Maximus, and elsewhere. His debut micro-chapbook, Landscapes, is part of Ghost City Press’s 2021 Summer Series.

Prose

Excerpt from Marriage Marina Mariasch, translated by Ellen Jones

Torch Song of Myself Dale Peck

The House Nikki Barnhart

Excerpt from Fishflies: the Men of the Riverhouse Marream Krollos

The Chinkhoswe J.G. Jesman

Tijuana Victoria Ballesteros

Agónico Marcial, 1960 - 1994 Israel Bonilla

Excerpt from Fieldwork Vilde Fastvold, translated by Wendy H. Gabrielsen

Reflections in a Window Cástulo Aceves, translated by Michael Langdon

The Waiting Dreamer Blue Neustifter

It Being Fall Matthew Roberson

Plans for a Project Bo Huston

Poetry

As Beautiful As It Is

every woman is a perfect gorgeous angel and every man is just some guy

Big Tragedies, Little Tragedies &

A Sudden Set of Stairs &

Hyde Lake, Memphis

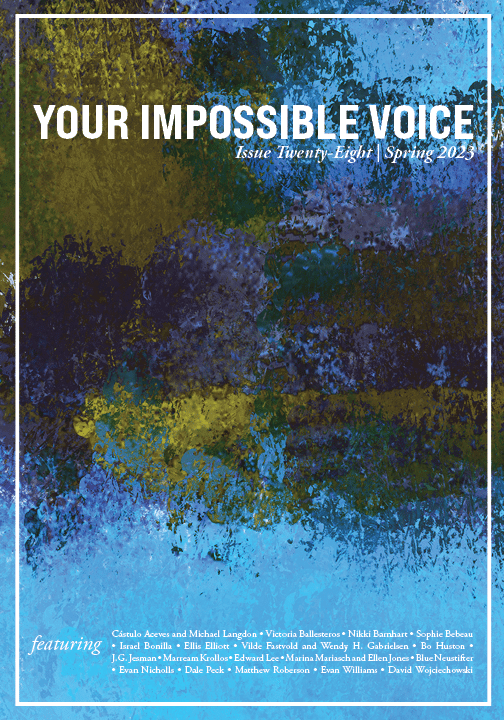

Cover Art

A Different Recollection Than Yours Edward Lee