Issue 27 | Fall 2022

The Border

Solomon Samson

It is Sunday. Paula is standing at the border.

A long line is passing under the hot afternoon sun.

The line stretches for miles across the terrain in a march that has claimed loads, food, and human beings. As the troop trudges past her, she trains her camera on it.

Since the age of nineteen, she has been seeking daring photographs for The Sun. Often she will fix her eye for hours, waiting for the best portrait. For more than a year, a growing wave of immigrants has been pouring across the border.

Some of them bear babies, flashing dry tears and bales of their last belongings. As they move along, they sing, gossip, stop, stare, and pray for slender rations. They are fleeing from their homes during a war.

As the caravan slogs along, Paula begins to roll her Pentax film. Around her torso is a Kevlar flak jacket and her thighs are wrapped in rough green jean shorts.

On her shoulder hangs a bag that sometimes bears a Nikon, an Olympus, a Contax, a Leica, a Canon, or a Minolta camera.

Each of the refugees exudes their own potpourri of pain. Some bear gaping gashes or are limping. One girl has a cast on her leg, while some are pale and footsore.

Without the help of a map, a lead, or a compass, they steer south.

After the first set passes, Paula digs into her bag and grabs a bottle of Marizio for a swig. After wiping her lips, she peers into the cloud of dust hanging in the air.

She coughs as she clutches her sleek camera. Everything is set in the tool. But she has to pause and make further adjustments. Also in her bag is a Nokia cellphone to call her office.

Too often, a photographer has to settle for poor shots—but not Paula. She has shot many locations before: the Sistine Chapel, the Irish bog, and the Eiffel Tower. But now, the blond photographer is taking shots of people pouring across an African border.

A few paces from her spot stands a rude tarpaulin tent that stores her pristine gear.

After the fit of coughing, she stands staring into the stale, barren miles. No flock of sheep. No gunshots. No clanking trains. No strafing planes. No airstrikes. No checkpoints. No garish signs.

Sometimes, it is so. Nothing will scratch the wide horizon, except in the evening when a jeep grinds through the sand to pick her up. Sometimes, all you can hear is the flap of her tent.

After an hour’s drought, another set of people pops into view. This caravan is even bigger. Paula cannot see it in a single sweeping gaze.

“Jesus,” she says, as she grasps her camera.

Some are holding long bamboo poles, some burlap capes, some baskets and smoking faggots, some rope ladders and jugs. Some are holding nothing. But they just can’t keep up with the plodding caravan.

At first, that’s all she sees.

After taking a few shots, a slender young boy bearing a falcon and a pale scar on his face comes into focus. On his shoulder hang a wooden bow and a quiver loaded with poison darts. Besides the brass crucifix around his neck and a skirt adorned with spent rifle cartridges, he doesn’t have a stitch of clothing.

After taking four more shots, Paula puts down her camera. She has taken good photos before—but she can’t miss this fleeting moment. This could be the golden chapter in her career.

It can make the front page of Time.

She will trade it to Fading Evening, White Egrets, Fragile Mist, Emerald Shore, Influx, Broken Mirror, Beaker Street, Bronzing Canoe, 100x, Crosses, The Stranger, Thereafter, or print it in The Sun.

After nine years of photography, she is yet to bag a big award. But with this one, she can get an IPA, a Canon and a Travel Photographer of the Year.

As the boy passes, she runs after him. In less than two minutes, she is squatting in front of the urchin.

Now, she can see him in firm black-and-white—his navel, his quivering lips, and the network of weals that sit on his rough, shimmering skin.

In the hot, blazing sun, he smells of stale smoke and fresh sweat.

“May I help you?” she says.

“No,” the boy replies, after mumbling an expletive in Adara.

“What is it?”

“Nothing.”

Since this journey began, this is the first time he will have spoken to someone.

“What is your name?”

“Etissi.”

In the passing minutes, he stands staring into her face.

“It’s hard to say,” says the photographer.

“Say what?”

“The name.”

He shrugs.

“That’s for you,” he replies, mixing English with his native language.

Paula sighs, after standing up.

For a while, she stares at him as if he belongs to a race once thought extinct. This is not part of her job. She is just trying to go the extra mile. But the look on the boy’s face tells her that it is not time to slow down.

“Just a minute,” she pleads. Sometimes, she has to do that to get the best shot.

As the minutes drag on, a long line of trekkers with bags of belongings march across the border. But she has to finish talking to him before another round of shooting begins. Better things may show up. She thinks.

As she speaks, a pregnant young matron with a bale of clothes on her head and a long pole drifts from an approaching group and stand close to the boy, peering.

Under her squashed ankara headgear peeps a cluster of scruffy plaits that combines glass beads and lumps of amber.

“Your mother?” says Paula after looking at her.

“Yes,” says the boy.

He is her young carbon copy, and no one can deny that.

“I see.”

“See what?” says the boy.

This trip has been on for days, and it shows on him.

Although he is hungry and gasping for water, his only passion is the young falcon in his hand. In the passing minutes, he holds onto it as if it is the only passport to the world ahead.

“You look like her,” says Paula. The waif heard her—but makes no reply. At the moment only the journey ahead compels him.

“Laplap,” he says, fondling the falcon as Paula scratches an itch under her white bra.

“From where?” she says afterward.

“Gefe.”

Paula sighs again.

“That’s far.”

The boy shrugs.

“Perhaps,” he says, after rubbing his prominent ribs.

“Hmmm,” says the photographer.

After a while, she digs into her white bag for a water bottle and a wafer.

In her first year as a cub reporter, she learned that most story hunters won’t trace the subjects of their essays and pictures—after taking their photos and letting them go. But Paula wants to be different. She doesn’t want to be another Kevin Carter. She wants to follow up.

“Take it,” she says, offering him the wafer and the drink. After popping the wafer into his quiver, he tries to read the emerald green label on the bottle.

“Marizio Pop,” he whispers. After a single gulp, he stares into her round, blue eyes.

“That’s its name.”

“It’s sweet,” he says.

“Always,” says the photographer.

After another gulp, the drink is gone and the boy blows soft air into the bottle, smiling in the wake of the hollow sound it gives. After a while, he raises his gaze to her.

“That’s all,” she says.

The boy smiles again. In gratitude, he grabs the falcon and spreads its flashing wings apart to show its long span.

As he holds the tapering wings, Paula raises the Pentax tool designed to fit into her hands. With a touch of a button, she gets his face, then a close-up of him and the falcon against the fiery sky.

“It’s fine,” she says, after staring into the camera.

“Let me see,” says the boy, pulling the camera. In the passing minutes, he presses the chic button. But nothing happens.

“It’s hard to handle,” he says, after a number of trials.

“It’s not.”

He watches after the photographer takes the camera from him.

“Anybody can use it,” she says, turning one part then another, leaving the boy to marvel. When he gets his hands on the camera again, he peers through the eye of the compact tool.

“See me,” he says, as he flips through the range of crude pictures in it.

“Yes,” says Paula after drawing closer to verify his words.

Afterwards, the boy stares at the shot for a long time. It is a shot that shows him in a skirt that covers only his genitals, as he flaunts the flashing wings of his mascot.

Like most great pictures, this one happened in a single flash.

“What is it for?”

“I will put it in a big paper.”

“Where?”

The woman, with hair the color of ripe wheat, hesitates for a minute.

“In America.”

“For what?”

“People to see.”

“See me?”

“Of course.”

“Why?”

“People like fine faces.”

“I don’t think so.”

Unlike the horde of people who slog along across the border, the boy is unwilling to tell her his story. But he listens anytime the photographer talks.

“Why?”

She wants him to tell her about the rape and the abuses and the killings—about how they had to flee one late evening from a sudden raid; about how Gefe is now a haunting remnant of burnt houses; about how the FFS slaughter anyone hanging a crucifix; about the murder of Father Alanza on the altar of St. Monica; about how he had to salvage what he is wearing; about how they stole their goats and pigs; about how they have to scavenge for insects, worms, grubs, and tap nectar along the way for food.

But instead of answering her, he touches a button on the tool after studying the sleek design on it.

“This is bent,” he says, after staring at a picture in the camera.

“You always get a shot the way you want it.”

After seeing a number of shots, she takes the camera from him and looks at the whole series of pictures. She will expunge a picture if it doesn’t live up to her vision.

“Not bad,” she says after having a careful look.

At this, he smiles, staring far.

Sometimes, it is interesting to stare across the border—the blowing weather, the road signs, the trails of hikers, the growing amount of trash and rags piling up the somber route.

As they stand, sets of people plod along: some in twos and threes. Some are wearing lip plugs and bangles. As they pass down the trail, some peep at Paula and the boy. But some haven’t got the time to stop and stare.

Every minute, the soft whisper of trudging feet fills the long, barren route.

Sometimes, there is no sign of a refugee along the border—but bandits smuggling rifles in the panniers of gaunt burros.

“No,” says Paula, when the boy hands her the empty bottle. “Why?”

“You can refill it with water.”

After staring at the bottle again, he looks at her.

“I need only the water in it.”

“It will help you,” she says.

After reading the label on the bottle again, he smiles.

“Thank you,” he says.

“Hmmm,” says Paula. “Who taught you to read?”

“Nobody.”

“How?”

“I don’t like school.”

“Why?”

“You get a whip for not remembering a lesson.”

“It is well,” she says.

“A border is many things. It raises fear. It offends. It comforts. It can be a projection that slashes through the horizon or a barrier raised to stop unfazed migrants and smugglers. It is also a boundary.”

The sun is still blazing.

In the blazing sun, the rifle cartridge cases around his waist dangle and tinkle.

“It’s fine,” Paula points at the spent rifle cartridges.

“I garner them around our village.”

“For what?”

“As a piece of evidence of the kind of weapons the FFS use on us.”

“I thought it’s a fashion.”

“No. I had no place to store them so I hung them on my skirt.”

“Oho.”

At some point, the boy squints as if a smoldering twig is placed on his forehead.

“What is it?”

“It is hot,” he says.

“That’s how it is along the border,” says the photographer. Apart from hunger, this terrain is so hot that traveling under it is enough to turn a boy into a skeleton.

“I see.”

“Why are you crossing the border?”

“For comfort.”

Paula smiles.

A border is many things. It raises fear. It offends. It comforts. It can be a projection that slashes through the horizon or a barrier raised to stop unfazed migrants and smugglers. It is also a boundary.

“A border is a state of mind.”

“I see.”

“How?”

“You are at the border like me. But you have everything.”

“Something,” she says.

“Water and wafer and a tool to shoot fine faces.”

“That’s my job.”

“What is it?”

“A photographer.”

“It’s tough.”

“That’s why I am here.”

Now Paula’s attention moves to that falcon. She can see the pride the boy feels holding the bird.

“Hold on, please.”

“For what?”

After scratching her long hair, Paula stretches her hand to pet it. All this while, it has been calm. But now it is raising its hackles. As it flashes its talons, the photographer flinches.

“It will stab me.”

“It won’t touch you,” says the boy, fondling the mascot.

“Laplap, Laplap,” says Paula.

The boy smiles, hearing the white photographer say the name of his mascot. After the falcon strikes again, they fix their attention on it for a while.

“She is attacking her reflection on your bag,” says the boy.

“I see.”

“And it won’t stop until you withdraw the bag.”

The photographer chuckles as the boy pulls the raptor from her. At some point, the boy sighs after glancing at his mother.

Now, a strong wind is blowing and scouring their faces. The weather is getting harsh. Soon, Paula will wear her goggles and wrap a scarf around her neck.

Her tent is flapping.

“It’s fine,” says the boy.

“I think so.”

“Is that where you sleep?”

“No.”

“It’s big.”

She shrugs.

“I crawl into it when the sun is too hot and when rain is falling.”

“It’s flapping.”

“It will stop.”

After the wind passes, Paula studies the falcon for a while.

“It’s calm,” she says.

“I got it along the way.”

“Can it fly?”

“I haven’t set it free since it fell into the clutch of my hands.”

“Has it eaten?”

“Yes.”

“What is that?”

“Whatever I get.”

“Like what?”

“Bugs and grubs and carrion.”

“Sell it to me,” says the woman who brings a whole photo studio to the border.

“Why?”

“It will help me.”

“What about me?”

Paula sighs.

The boy’s response is sapping her strength. After a while she offers the boy another bottle of Marizio.

“For the falcon?” he says.

“Not at all.”

The boy pops it into his quiver.

“No,” he says less than a minute after, when his pet launches another strike at the photographer. To appease it, he dips his hand into his quiver for a white grub. Bearing a quiver makes him look like an ancient traveler.

“Put the quiver down,” says Paula.

“No.”

“Why?”

“It’s been there for days.”

“It is heavy.”

“It is not.”

“Let me see.”

The boy watches as she grabs the wooden tool from its strap.

“It’s light as a camera,” he says.

“Is that how you feel?”

“Yes.”

“It’s because you hang it.”

“Perhaps.”

“That’s it.”

In the meantime, Paula peers into the quiver. It has a slender list of items. No sweets, no bananas, no figs, no ratoons, no dates, and no extra sandals for the long journey.

Besides the bunch of darts, the pouch contains a grub, a rag, a flint, a toadstool, and a slab of honeycomb.

“We hunt for it,” he says as Paula holds the slab.

“What about this?” She shows the flint to him.

“We make fire.”

“Who gave it to you?”

“My father.”

“Where is he?”

“My father?”

“Yes.”

“He slumped after tearing up some miles.”

“Where is he?”

“We left him there.”

“Why?”

“Nobody can carry him.”

“Hmm.”

“What?” The boy stands staring at her

“See,” she says, pointing to the pale scar running down his face.

“What?”

“This?” she says.

He got the angry weals on his skin while elbowing through scrubs and thorn bushes along the way. But it is hard to pin down where he got the scar on his face.

He contemplates for a while.

“It’s a tear.”

“It is deep.”

“I got it while struggling to cross a pass.”

“How?”

“It’s strange,” he says.

She feels his head.

“You need aspirin.”

“I am well.”

The photographer stands thinking.

This is Africa, but not the part where you see a caravan of Bedouins dragging bags of salt on loaded camels as they slouch across long, barren miles.

“Eat the wafer,” says Paula.

“I can’t swallow it.”

“Why?”

In response, he opens his mouth wide.

“It will get better,” says Paula as she inspects his inflamed throat.

“That’s what I’m waiting for.”

Paula shut her eyes for a while.

Often she travels with a bag and a camera, listening to stories and taking shots. After this shoot, she will take a backpacking trip to Mali.

“Sit down,” she says after looking at the boy again.

He needs another shot. He is fine. But he won’t understand. Beauty is about being yourself.

“Why?”

“You need to rest.”

“Not now.”

“It will help you,” she says.

Anytime she looks at the boy, he seems to her a member of a race on a march towards extinction. And it won’t be bad if she adds more of his pictures for posterity to see.

That’s what she does. She works with a company that cares about your image.

As this group moves along, they will find other sets of refugees washing their clothes and pouring water to cool off in a foul stream. A rumor that there is a UN food center 300 miles away is perhaps what emboldens this stream of tired refugees.

Time is passing. The boy’s mother is tugging at him for a gallop into the unknown. All this while, her bundle remains atop her head as she witnesses this moment of tenderness.

“Muje, ka ji,” she says, as she tugs at his skirt.

The boy stares at Paula.

“Time is going,” he says.

If she whips out her cellphone, she will see fifty-three missed calls. But this moment is for the boy.

“What is it?” she says.

“She wants us to go.”

“I want to ask for something,” she says, after staring into her sleek camera again to see if her shots can earn a place in a big paper.

“Why don’t you come along?”

“I can’t,” she says.

After a while, the boy stares at her.

“Our journey is far,” he says.

They need to close the gap with their companions, and time is not on their side.

The photographer sighs, after stealing a glance at her Cartier watch. It is nearing sunset. Soon, a whining jeep will be grinding through the sand for her. If it fails to come, she will flag a truck for help.

“Stay with me.”

“No.”

“Listen.”

“What?”

“Stay.”

He ignores her.

In this terrain, even road signs jumping at you from a rusting billboard can pass as company.

“Please.”

“No.”

“You hate me.”

For a moment he stands like a monument commemorating an epic journey.

“No,” he says.

“Then why?”

“I want to cross the border.”

“Why?”

“To see things for myself.”

“How?”

“No.”

“Tell me.”

“Nothing.”

Paula coughs again.

As a photographer, her shots have appeared in the Wall Street Journal, Bronzing Canoe, Stern, Le Monde, and some have been mounted at Visa pour l’Image. But here she is struggling to retain the attention of a shirtless boy refugee simply because she wants to earn a place in the world of image.

He clutches the bird and cringes when Paula tries to stroke it.

“I won’t seize it,” she says.

“But you want to touch it,” says the boy as he cuddles his most cherished possession.

“Of course.”

“It is sleeping.”

When a gust of rushing wind comes, it ruffles the falcon’s feathers, making the boy blink his eyes and the photographer hold a piece of rag over her nose to stop a speck of dirt from hitting her lungs. Soon, the approaching evening will usher a nip into the air.

“You have nothing to drive away the cold,” says Paula.

“I’ve been like this for days.”

She shrugs in frustration.

“But there is no one in sight to ask for directions.”

“That’s how we got here.”

“Take,” she says, handing him the quiver.

“I remember.”

“Anything else?”

“No,” he says, after hanging the tool on his shoulder.

Without a sandal or a slip-on, he has to log the extra miles ahead. He has walked a long way to this point. But this is just the beginning of a long, hard journey.

As the minutes pass, he is getting thirsty again. But he is not going to touch his drink now—if he finishes it, he’ll have to gulp foul water from the hollow of his hands down a narrow gorge. But if things get tough, he can hold on for twelve hours a day without food or water.

“Etissi.” Paula whispers his name for the second time.

“Yes,” he answers.

But at this moment, his only concern is how to plunge into the future. Paula stares at him again. He is too young to hang on longer than this and no pledge can stop him.

“I can’t get along without you,” she says.

“But you have my pictures.”

At this, Paula casts a long gaze at him. Her strength is petering out, and a stronger wind is blowing down the unforgiving terrain.

She is here to record the saga of a people on the move, and she has got all the shots she needed. But she wants more than that. As she regards the boy, she hopes that he will not forget her. But often, a woman forgets sooner than a man.

Before the boy and his mother set out to join the ragtag party, she whips out a white paper from her bag and scrawls The Struggles of an African Urchin.

Under this caption she scribbles his name in block letters.

“I will find you,” she says.

He smiles.

“I won’t stop for someone again.”

“But thirst can stop you.”

“I don’t want to think about it.”

In the searing heat and dust storms of the day, the procession slouches down the sterile terrain. As they move, Paula stares, fixing her sight on the boy until the crowd is lost in a haze of distance.

Paula remains there for a while, then goes after the exodus.

About the Author

Solomon Samson is a Nigerian writer who enjoys writing short stories, essays, and poetry. Besides writing, he teaches Jolly Phonics to children. In his spare time, he enjoys taking casual walks and getting a feel of nature.

Solomon Samson is a Nigerian writer who enjoys writing short stories, essays, and poetry. Besides writing, he teaches Jolly Phonics to children. In his spare time, he enjoys taking casual walks and getting a feel of nature.

Prose

Nonie in Excelsis (Excerpt from About Ed) Robert Glück

Dirk Julia Kohli, translated by Rob Myatt

Panthera onca Jasleena Grewal

The Border Solomon Samson

Tikibik Dominic Blewett

Mistake or Accident Laurie Stone

Excerpt from Mice 1961 Stacey Levine

The Cathedral of Desire Nina Schuyler

The Gorge James Warner

In This Case, He Killed an Innocent Person Carla Bessa, translated by Elton Uliana

A Chinese Temple in California Alvin Lu

Poetry

you have become an archive. Lorelei Bacht

thunderclouds

On the Things I Did at the End of the World Beatriz Rocha, translated by Grant Schutzman

In this movie David C. Hall

Spot Rolla Barraq, translated by Muntather Alsawad and Jeffrey Clapp

Let There Exist For Us… Eva-Maria Sher

That I Would Cameron Morse

Surf

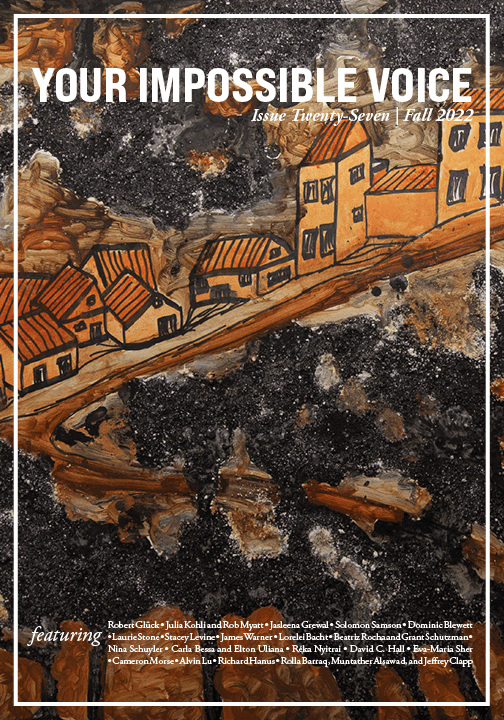

Cover Art

Image 001 Richard Hanus