Issue 27 | Fall 2022

A Chinese Temple in California

Alvin Lu

Arrive at a green clearing. To the side of the road, in a depression by a brook on a promontory, lies a structure that seems not from around here. Pull over into overgrown grass. A path has been roughly cut through it to the front door, which is flanked on either side by vertical wood panels, with seven Chinese characters debossed into each:

Move in four directions, meet superior people

Through the four seasons, encounter good fortune

After being on a winding dirt road under a dense forest canopy for so long, the clearing feels as wide as the sky upon entering it, but it’s really a narrow space, a deep well. Several layers of trees, woven so tightly together as to seem impassable, stand in every direction. The town just passed lies down the road, not so far away, in easy walking distance, but feels inaccessible.

The workers have finally arrived, with this unimaginable locale on their minds and written on their papers, since as far back as Hong Kong, or further even, since Toisan.

That last stretch, up the Sacramento River and overland, which looks on a map like the least part of a trip from China, of all places, was still not easy, coming through the valley and up into the cooler air. What goes through their minds as they take their first look around? This is all their world now, as far as they can countenance it, for the return trip is merely a frame for the more pressing present, which is wilderness. There is no system of society as far as the mind can go. The woods are close and unnavigable. There is only the moist, chilling mountain air. Their only assistance, the terms of which are yet to be divulged, is this building, summoning superior people and good fortune.

At least others are already here, but that first hint of fear will return with a vengeance when the land and its hostile residents swallow one of them up, with disconcerting frequency.

What’s surprising is that, with lumber so plentiful, the exterior would be painted brick. A waist-high slat fence opens onto a porch spanning over a pair of carved wooden doors, an entry that suggests something more extravagant than just another cabin in these northern woods. Open those doors to find, here in the middle of “nowhere,” far more than that, in fact: a more advanced and sophisticated culture, built in Canton and brought here. Why? Nobody had the wherewithal to do this kind of work here. This sensibility puts the county courthouse in Auburn or the great metropolis of Whiskeytown, now sleeping at the bottom of a lake, to shame.

There isn’t even anything like this in San Francisco. The delicacy of carving, on lattice-wood screens and columns, seems similar to temples in Taiwan, which date from around the same time. The finely woven dreams of the south. Like the ones in Chinatown, it wouldn’t have been shipped whole. Did the workmen who received the pieces carried by cart and mule know what they were doing? There would be, and still are, strict rules for feng shui. Did the delivery come with instructions? Or did the builders just go by their infallible memories? Mass recollections make up for quirks of individual omission or preference. Trust the group.

Lord Kwan and the Northern King are seated side by side in the central spirit house, under a high, vaulted roof made of wooden planks. Flags and drums, with phoenix-dragon and sun-moon designs, surround them, colors muted by soot. Inscriptions on wooden boards name every donor, Wongs, Chins, Lee, even for the smallest amounts, seventy-five cents, a nickel, accompanied by strips of writing, by now rather distressed looking, of admonitions toward correct filial and community behavior. Down a hall are travelers’ quarters, a couple of rooms each with its own kang. In the provisions hall, tea is served, no liquor, under postings of news from other mining towns. Some of them, it is noted on a makeshift plaque, were delivered by carrier pigeon.

It isn’t a temple anymore, not without incense to light the altar nor any offerings, oranges or otherwise. A temple isn’t a temple without just those two things. It lacks life and turns into a hollowed-out ruin. Do the gods feel abandoned? Are they just waiting for someone to take back up the cause? It’s enough to make you want to go and light some joss sticks yourself. Care seemed to have been taken so that things seem to be in the right places, so there’s been some upkeep, the floors swept, but the impression, to anyone who’s been to one of these things, is of chaos, of death, the lineage snapped off, which is the worst, because more than anything, the spirit world, far from being the realm of the dead, needs to be alive. This is why Chinese ceremonies are noisy.

Out the doors is a perfect view of the clearing. The position seems strategic, and you see, entering from one side of the tableau, somebody or something coming out of the trees, its movements jerky, kind of loping, stepping over the high grass. Why is she coming from inside the woods?

Wearing a puffy green jacket, she shakes droplets off before pulling back her hood, revealing white hair underneath. Boots stamp on the porch.

“Did you get a look around? See the bats?” She points at the rafters. “Most people who come have never seen anything like them. Usually you’re talking dragons or phoenixes, right? Lions too, I guess. Frogs, even. We had some scholars from southern China up here last month, who said they only have artifacts of bat designs, from isolated villages, very rare. These are the best preserved in situ examples left in the world.”

“Why bats?”

“No one knows for sure, but probably because they’re a homonym for happiness.”

“Fu and fu. Right.”

She steps past the spirit screen. “That’s Lord Kwan. I’m sure you recognize him. Have you made an offering?”

“No. There’s no incense.”

“Back when the Hueys were still in town, they’d make offerings and bring friends and visitors, some of them from as far as San Francisco. They’d pray to Lord Kwan for success on their kids’ high school entrance exams.”

“Like for getting into Lowell?”

“Bet you know all about that, right? There used to be an urn here for offerings. They’d fill it with whiskey, but it’s gone now. Maybe got stolen. This is the maze. That’s because evil spirits can only go in straight lines, can’t turn corners.”

“I’ve heard about that. Who are the Hueys?”

“A family, but after the parents passed away, the kids, who moved, I think, to Dixon, couldn’t keep things going. They’re old too now, and their grandkids moved out of state, but I knew Old Huey. He worked in the vineyards, down in Sonoma, then moved his family up here. Made the most amazing kites. Those pennants, too.”

“I had no idea there were so many Chinese around here.”

“A lot of the old towns burned down, if you know what I mean. After Old Huey passed away, the county did what it could with this, but now it’s just volunteers like us. We don’t keep it up the way the Hueys did. It’s not an active temple that way. I guess you could say we keep our distance. Our efforts are preservative, but it’s gotten to the point that we might have to leave it to the elements, if they can’t work something out. It’s a shame, it’s a wonderful thing to see, but this town is just too remote for tourists to make the trek.”

Detach it from its foundation. Everything in it, once unmoored, might crumble into dust, though. Even if it didn’t, the road out the clearing might be too narrow. How would you get it through the trees to make the journey hundreds of miles to lower, drier elevation? Remarkable it hasn’t been destroyed by fire, flood, or looting, by forces of nature or forces of contempt. Let’s say cost was no object. How about a helicopter? Drop cables down into the clearing or something.

She walks straight back the way she came, into the trees. As the crunch of her footsteps falls away, certain elements return, having never gone away, the wind blowing through the treetops, the overwhelming smell of pine, the screeching of blue jays, and the subtly maddening, unblinking immensity of the forest itself. How would you be able to take it? There would always be someone standing in the corner of your eye, and there would never be anybody there.

The drive back is a descent, from twisty alpine roads to freeways, the air growing warm and soupy. What had merely been outposts in the wild begin to multiply, out from the “country” into ever denser patterns of roadside structures, signs, and trucks. Speed makes the transition imperceptible. Signs demarcate cities, one after the other, but in reality it’s all one city. The ball winds tighter and tighter the closer you get to the center of it.

Before then, though, still on the outskirts, which seem neither country nor city, you get hungry. Two options make themselves known, with nothing else around in the twilight, both Chinese, as it turns out. An ol’ fashioned American-Chinese joint, occupying a shack, family-run in all likelihood, all your order made by one guy at the same wok. The other, down the road, but the blazing sign readable from here, an all-you-can-eat buffet, run by immigrants from Wenzhou probably, offering a selection of every flash-frozen edible imaginable. You’re looking for something lonely and quiet, though. So you go with the first option, where there is only one other car, probably the proprietor’s, as you pull into the gravel lot.

Just then, caught in the headlights, in the midst of your turn, you see, plodding down the highway, that figure, going your way. No umbrella, no coat.

Inside is just an old couple, husband at the stove, wife on the cash register. A red-with-gold-leaf calendar is pinned to a wall, depicting some unidentifiable animal. You don’t remember what zodiac year it is, or will be. Inevitably, Lord Kwan, known for his soldier’s sense of honor, scowls down from the ceiling corner, facing the door.

You’re facing the same way. You’re given disposable chopsticks, soy sauce in little packs. At some point, looking up from your plate, the door opens and shuts on its own. Nobody walked in. Lord Kwan does not blink, and it is the lighting, the time of day, or this roadside location, but, like something out of Liaozhai or some Edwardian cardboard paste-up of it, it seems this will all turn out to be a hallucination and the whole time you were eating sand.

Whatever had come in eventually leaves, but doesn’t go far. Feel it circling the cabin, which is all this is, round and round. Maybe you should have gone to the other place? But chow mein there would have just been in a reheated tray at a buffet station, picked at by locals and highway passersby like yourself, eating food hand-prepared a world away and miraculously flown off to obscure corners of the planet, like here, in a kind of inverse process of when miners would bring their dirty jeans to San Francisco and get them washed in Hong Kong. Buffets are the new town squares. There would be talk, among the college kids and truck drivers, of odd phenomena in the hills, unseen forces that move as fast as a car, all a piece of the stoned, tall-tale culture in these parts. Sacrifices by the river. A “mysterious” incident that was not so mysterious, after all.

Rattling outside. Cash only. This modest concern, linking the civilized and wild worlds, is a hub in another flow, of money. The old lady occupies that exact cross-current. Back outside, the mountain air follows the highway down. Wind roars through the tops of pine trees. Walk, hunched over, arms crossed, to get to the car. The night sky is serene. The moon floats in it. The only thing following you is headlights.

It grows lighter. It’s a long, featureless drive. The scenery becomes more geometric, yet barren. The inner has become the outer, and things are getting more and more remote. All impressions, which were your only souvenirs of this trip up north, already lose their potency, too delicate in actuality, and dissolve in the thicker, sea-level air.

We thought Anaïs wouldn’t be used to the long car ride—after all, the drive from one end of Taiwan to the other takes less than four hours—so we had her sit in front, where she wouldn’t get carsick and could also get a better look at the road. Nobody else seemed interested in the view. That put me at the wheel and the architect and geomancer in back, the arbiter of mystical space seeming to take up twice as much room as the designer of actual space. In the rearview mirror, one looked like he was pushing the other out the door, but the architect didn’t complain. In fact, he was giddy.

It was a clear day, and the great bowl of the bay revealed itself at sunrise. We drove past Petaluma, Santa Rosa, Healdsburg, Cloverdale, Hopland, Ukiah, and Willits. After Leggett, we began the climb into the forest and Anaïs took out her sketchbook. At some point, apparently, she’d drawn the faces of the two backseat passengers, good, almost satirical likenesses. Now, instead of trees or the road, she began doodling eyes, as was her habit, although this time I realized they were Buddha Eyes, complete with a security camera poking out the urna. She’d copied the roadside mural fronting a pot farm outside Laytonville.

“What if we can’t move it?” the geomancer asked.

“Do you think the spirits might be angry if we try?” the architect asked, out of apparently sincere curiosity.

“That didn’t occur to me, but there’s a chance. I was just thinking the building might be too old.”

The architect sighed and turned toward the window, realizing for the first time our surroundings had changed.

“Where are we?”

I got gas. It was decided we stretch our legs, and for the architect, grab a smoke. We only made it a few minutes into one of the nearby groves, though, before the three of them parked themselves on a log, the two men not used to walking and, each for his own reasons, utterly uninterested in the environs. Anaïs, who’d been quiet the drive up, became engrossed in her sketchbook, rendering the lush fern understory in thick, bold strokes.

Toward the mountains, the weather turned. Clouds from the coast hung low, blotting out the peaks we were approaching. Once in the high country, the road washed away in mist and drizzle. Snatches of vertical scenery appeared through breaks in the fog, scrolling past. Looking pale, Anaïs put her book away. The two in back closed their eyes. At some point, as the car pointed toward the sky, the sun seemed like a blank disc in front of us, and in the middle of the road appeared a floating cloud. There wasn’t another soul around, if the trees, mountains, rocks, and clouds didn’t count. To keep from going off into a gorge, I trained my focus on what was directly in front of me and found myself driving into what seemed the same cloud again and again. Behind it and the rain seemed to be a white light, pulsing faintly.

On level ground again, the cloud returned overhead, stretching from one mountain ridge to the other, and the river appeared, parallel to the road, waters at first glance still and clear, but on closer look, moving in a flat, swift current of black stone, threatening and higher up the banks than I remembered. The path continued, familiar enough, until it wasn’t. We ended up in a town in a luxuriant ravine setting. At first I thought we’d arrived, but from the other side somehow. I must have taken a wrong turn, because I didn’t recognize anything. We pulled into a gas station. From the look of it, it was one of the old rail towns, maybe what had once been a glittering Chinese camp, with the temple close by as the central gathering spot.

“Where am I?” That broke the ice. The attendant, who was also, it appeared, the waitress, cashier, and cook for the attached diner, chuckled and mentioned, in a smoker’s rasp, that the bridge had been washed away by last week’s rain. What I’d thought had been a particularly swollen section of river, coming to the edge of the road, had been where it was. Visibility was so bad, I hadn’t seen the road closure.

“A ghost? They don’t bother waiting around to find out. Besides, they know all the lore.”

“Land changes around here.”

“Literally washed away?”

“Got broken up pretty bad. You’ll have to loop around, might take you another hour and a half, maybe two hours, depending on how fast you drive.”

“Two hours?”

A customer I’d been keeping track of out of the corner of my eye, wiry, goatee, neck tats, came over from his counter seat. “You headed anywhere in particular?”

“You know about the Chinese temple?”

“If that’s where you’re going, there’s a spot you can drive across and walk up. It’s woods from there, but there’s a trail, not that far at all.”

“You mean across the river?”

“I can show you the spot. It’s shallow.”

“Water looks high today.”

“It’s been receding last couple days. It’s crossable right now.”

We all looked up at the flat-gray sky.

“Doesn’t look like it’s going to rain. Not today,” the attendant said.

“I wouldn’t try it in that, though.” He pointed at my car. “I can give you guys a lift, if you want.”

We all piled into his truck bed. Probably not a good idea to leave the car parked on a highway shoulder where only one of the local tweakers knew its, and our, whereabouts, but by now we were all just going with the moment, and the car itself was hardly worth worrying about. We curled up in the bed. Only Anaïs stuck her head out.

“How are we going to get back?” the geomancer asked.

“I dunno. Catch a ride back from town, probably.”

Once across, we climbed out of the truck. “It’s all high ground, so you don’t have to worry about it washing out or crossing streams. That’s why I thought of it.”

“Thanks a lot.”

He headed back, waving from the window.

It occurred to me it’d be a funny story to tell his buddies, ferrying a motley crew of Chinamen so they could worship at their weird, old temple. At the same time, it made perfect sense, didn’t it? It’d explain the curious structure in their midst, except that was not what we were here to do at all.

The first quarter-mile or so was a steep incline, and we were huffing and puffing. Coming down, we saw our driver was wrong. The trail was now streaked with rivulets pouring out of the forest, as if a precursor to a flood, but while the flow was steady, it didn’t grow any worse, and we were able to get over deeper water on rocks or logs or by skirting it on slippery hill slopes. It made for slow and muddy progress, though. The woods were a tangle of trees, rock, moss, fern, and stands of wild blackberry and rhododendron. The air was so moist it appeared soft and out of focus. If not for the trail, it was impossible to think how anyone could have figured their way through it. Even for my two colleagues, who were as desensitized by urban life as anyone I knew, the forest began to make an impression.

“Why in the world would anyone, much less a bunch of Chinese, build anything in this godforsaken place? How did they even get here?”

“We’re not there yet. I’m sure they went by feng shui.”

“Feng shui? I see lots of water, but no wind.”

The size and incomprehensible depth of the vegetation made it seem like being in one of those funhouses where the proportions change as you walk across the room. My companions made like tourists and stood side by side in front of a tree trunk wider than the three of them put together. The deeply fluted columns dripped down from the sky and hardened as they touched the earth. It was all an adventure, going back to when we crossed the Golden Gate Bridge, but as the monotony of the path rolled on, good humor wore thin. I wasn’t an experienced enough hiker to imagine how far in we were. Given everybody’s lack of conditioning, probably not very. There’s that point you begin to wonder whether you missed a fork somewhere and are going down the path to oblivion. At the same time, you don’t want to backtrack on speculation that seems based on nothing but impatience and exhaustion. The trail becomes aggravating and unresolvable.

… and then a break in the trees. The clearing was shivering with water, as light came down through it. When the wind blew with the sound of the waves, it sent drops flying from the canopy, generating the effect of sun showers. There it was. At first, my fears came true. The temple looked half-sunken under water, but on closer look, it was only a pond filling the depression that led to the promontory the temple was built on, making for a kind of moat. That arrangement revealed the foresight of the builders.

We wouldn’t be able to do better. Once inside, though, we tried. We put down our packs, and before anything else, the geomancer went to the altar and lit the sandalwood incense he’d brought with him, made ritual bows to the long neglected gods, and inserted them into the censer. Dust and smoke swirled around him. He did the same with offerings of rice wine and fruits. His rustling and murmuring formed a backdrop to the dead air of the interior, which had stayed toasty dry in spite of the humidity all around us, another testament to the fastidiousness of the original builders. Meanwhile, the rest of us got to work sketching and taking pictures.

The architect had us beam photos to his computer. He would then drop them into a software program, which immediately produced a kind of 3-D model. The two candles on the altar and the glow from his screen, which lit up his face so it resembled a hologram, were the sole sources of light, besides what crept in through the annex window.

While he set up the model, he had Anaïs go around the divine hall with a tape measure yelling numbers at him.

“How’s it going? Any signals?” the architect asked the geomancer.

“Like anything that hasn’t been used for a long time, it’s going to take a while.”

“So it’s like an old car?”

“Very much the same.”

I was watching them from a spot by the entrance, where I was measuring the height to the ceiling. Now the geomancer was going around the room with his feng shui compass. While we were tracing the physical world, I could almost see, in the grotto-like darkness, lines not unlike what connected our phones to the architect’s laptop, crossing the room, breaking it down into perfect geometric shapes; octagons, I supposed. This was superimposed onto whatever we were thinking of as the space. In spite of the light-heartedness in the geomancer’s voice, the expression on his face was serious as he stared into the recesses of the hall, the infinity behind the altar, where the gods resided. His mouth kept up the banter, but he wasn’t really with us.

“Aren’t they going to be mad at us if we move it?”

“Nobody’s been here for them for so long, why would they mind? Honestly, I don’t know.”

“They seem to need a lot of appeasing. That’s all I ever see you guys doing, appeasing.”

“No different with living people. At least spirits and gods are reasonable. That’s why I got into this line of business. They’re rational.”

“Ha ha, you may be right.” The architect turned to me. “What do you think? When I first heard you mention it, I thought it was going to be a shack, but this … ”

“You think Gong will be up to this?”

“He’s the best I can think of. I don’t say it lightly, but he’s a kind of genius.”

It was an odd term to use for a contractor, but I didn’t think anything of it at the time.

The geomancer stayed inside while the rest of us went to measure exterior dimensions. We discovered the sun had momentarily come out, making the clearing shimmer with light that glanced off water droplets scattered over foliage like jewels. It was the brightest it’d been all day, but we didn’t have much sun left. We hiked down the road, the same one we would have come in on if the bridge into town hadn’t been washed out. I remembered the tight clearance between the two massive trees, not far from where the forest ended.

Anaïs and I held the tape between us.

Too narrow. By far.

The architect grumbled, “Didn’t need to come all this way for that. You can see it just by looking.”

“I should’ve double-checked when I came out last time. That structure’s bigger than it seems.”

“What’re we going to do now?”

Anaïs, who, I realized, hadn’t spoken a word since we arrived at the temple, dropped the tape measure, leaving me holding one end of it, and tramped back toward the temple. She stopped halfway, staring as a plane of light passed over it.

Now in its glow, she held her hand out in a chopping gesture, slicing it through the air, squinting.

“Cut it in half.”

She knelt, got out her book, and drew a quick sketch of the structure: a box capped with upturned curves for eaves, then a line cutting through it dead center.

“Right in two. Look!”

A fly? If you took that buzz and played it through an amplifier, it could be that. At first, you thought it might just be the sound from inside your head as it was being squeezed through a hole in the wall, because that’s what this awful headache feels like, but no. It’s definitely external. Crawl out of bed, feeling bloated, out the room, then tumble down a narrow spiral staircase. What did they put in that tea? When did the page turn? At least those crazy villagers left you in one piece.

Outside the pagoda tower, there was no more village nor any mountains, only fog. Move through layer after layer of the white stuff, sensing shades moving in the same direction, just beyond the next layer. No sound but that buzzing.

Lap of water. No mountains or village, but a lake, obscured. The sound of wood bobbing in water.

On board, steady.

Moves smoother than one would have thought. Water parts to either side, gently, but no sense of progress. Just floating. Mist moves fast, curling off the surface, as waves turn into clouds. Outlines of pavilions are revealed. Other vessels, steered by phantom boaters, appear at a distance. Can’t see flowers or bushes, but the fruit scent of osmanthus blends with the fog, making for an odd effect. Fish swim just below the surface. Something up ahead. A log or an unmoored, abandoned skiff. The shore arrives abruptly.

On land it is unexpectedly dark due to the canopy, whose treetops are lost in the clouds. The ground is soaked, as if a nearby tributary emptying into the lake were overflowing. The smell of osmanthus has been replaced by the sharper scent of pine. The lake is behind you now, concealed on the other side of the forest, while above you, blue jays are poised in the act of taking flight, as if it were possible to arrest time.

You come across bunnies and a deer carcass on the trail, and then, up ahead at a distance, a group of men. They are all around the same height, each of them wearing worn-out baseball caps. You don’t understand the language they’re speaking, the musical, almost jazzy dialect traveling on the wind, through branches and undergrowth, mixing with the bird calls. They keep their backs turned to you. Two of them carry something between them. From the sound of it, the discussion among them is growing more animated, with gestures. At one point, one of them, who seems to be the leader, throws down his cap. He picks it back up, throws it down again. Another one, smaller and thinner, stands apart. Others point at the latter. He waves his hand dismissively, moves on. The others follow. The leader hangs back, bringing up the rear. Now the whole group is convulsed in what seems like laughter. The mood changes quickly, or were they just playacting?

Something in the forest makes you a little crazy. The sun emerges, or rather, it’s the treetops that have emerged as the fog peels back and the branches radiate light. You bask in this newfound warmth, not wanting to move. You can’t see the sun itself, which must be behind the tall trees, close to the horizon, but the pale face of the moon, full or almost full, peers through a break in the canopy. The light remains constant, but with each minute the rays bring less heat, and you can feel the temperature drop—and it can drop fast here—as you lie there in the grass. Meanwhile, the men have all gone into the temple, which is sitting in the middle of the grove, halfway submerged in a pond. They’ve laid down a plank so they can cross over to the entrance. All streams in the forest seem drawn into this sink.

You’re awakened by that buzzing sound again. At last you’ve located it, and it seems to be coming from inside the temple. Now there are men standing around outside, but it’s dark now, and they’re working by halogen lamps plugged into a portable generator, so you can’t see them so well. In the shadows cast by the lamps, which form a kind of stage lighting, the temple is tied down by ropes. One of them gives out a yell, and the men pull, followed by the sickening shriek of splitting wood. Only now is it apparent there have been planks laid all around the building, not just to the front door.

For a while, nothing happens. Then a pair of trucks come down the road and park on either side of the temple. They tie the ropes to the tow hitches and, once given the signal, the trucks move, in opposite directions. By some miracle, but it’s no miracle, just ordinary ingenuity, illuminated by daring, Gong’s “genius,” the temple opens like a book.

The work continues into the night. At some point the last of the trucks rumbles off, with its unwieldy freight in tow. They shut off the generator. The sound of the clearing returns to the forest. It’s not totally dark, there isn’t a cloud in the sky, and everything takes on the serenity of things when only seen by moonlight. There are just two men left. It’s not obvious, from where you are, who they are, or if you’ve seen them before. They stand on the little hill where the temple once stood, outside the foundation, looking over the pool in front of them, smoking cigarettes.

The moon is vividly reflected in the pool, almost a perfect mirror image and just as bright. The men stare at it. Then the reflection begins to rise, no longer a flat image on the surface of the water, but a sphere. As its ascent continues, it becomes apparent the moon, or sphere, is a head, and the rest of the body it’s attached to emerges out of the pool along with it.

A ghost? They don’t bother waiting around to find out. Besides, they know all the lore. They bound down the plank straight for the road, the same way the trucks went, into town.

The figure pulls itself, dripping, onto the promontory, before hopping in pursuit. It all happened so fast. It could be just you, but it seemed to be laughing. Or shivering? Funny or cold? This might have all been a prank, in a land with a long and illustrious history of them, but what do you know?

About the Author

Alvin Lu is the author of the novel The Hell Screens (Camphor Press, 2019), along with short works of fiction that have appeared in Firmament, new_sinews, Denver Quarterly, and previous issues of Your Impossible Voice.

Alvin Lu is the author of the novel The Hell Screens (Camphor Press, 2019), along with short works of fiction that have appeared in Firmament, new_sinews, Denver Quarterly, and previous issues of Your Impossible Voice.

Prose

Nonie in Excelsis (Excerpt from About Ed) Robert Glück

Dirk Julia Kohli, translated by Rob Myatt

Panthera onca Jasleena Grewal

The Border Solomon Samson

Tikibik Dominic Blewett

Mistake or Accident Laurie Stone

Excerpt from Mice 1961 Stacey Levine

The Cathedral of Desire Nina Schuyler

The Gorge James Warner

In This Case, He Killed an Innocent Person Carla Bessa, translated by Elton Uliana

A Chinese Temple in California Alvin Lu

Poetry

you have become an archive. Lorelei Bacht

thunderclouds

On the Things I Did at the End of the World Beatriz Rocha, translated by Grant Schutzman

In this movie David C. Hall

Spot Rolla Barraq, translated by Muntather Alsawad and Jeffrey Clapp

Let There Exist For Us… Eva-Maria Sher

That I Would Cameron Morse

Surf

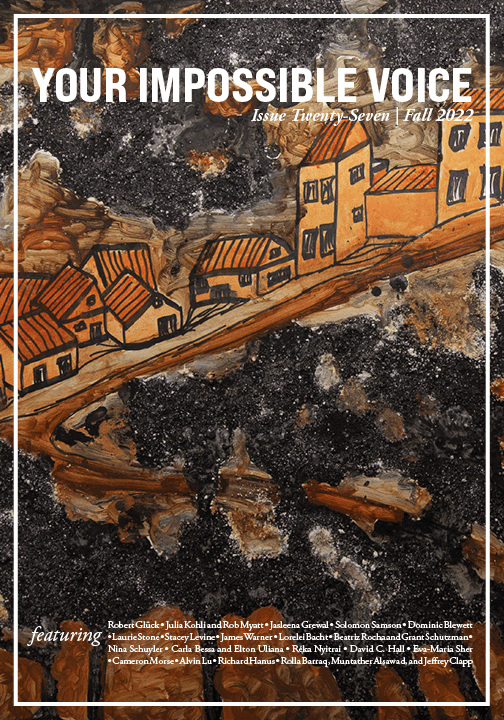

Cover Art

Image 001 Richard Hanus