Issue 30 | Spring 2024

Two Tales

Alvin Lu

The Glimmer of Chance

The first time I saw S— was at a fundraiser for a local politician, an upstart representative of the wrong side of town, gearing up to challenge the mayor in the upcoming election. My son and I were walking back from the library and passed by the event, which was being held at a hamburger joint that was also a favorite hangout for cops. His best friend’s mom, A—, was inside. We all knew her; she had been a beauty queen in high school, crowned Miss —. Now she was a single mother. She must have been dating S— by then, because he was there too. She saw us first and waved. As I was about to enter, a black sedan pulled up to the curb and the local supe stepped out, just as I’d seen him do on television. My son greedily grabbed a sugar cookie from the plate A— was holding out, but she was no longer paying attention to us, lavishing smiles on the pol and the media scrum tailing him.

The next time was at a birthday party for A—’s daughter. She’d become friends with my son due to their being the two brains in the class. Since most of the party was girls and moms, I found myself sequestered with the only other “dad,” actually the boyfriend. This was the first time S— and I talked. He was great with the kids, cutting cake and blowing up balloons. You would not take him for one of the most feared men in the city. I did not. His head was shaved, and he sported a mousy mustache. A short guy, smaller than me. It turned out he was holding a lot inside of him that could uncoil at any moment.

This is the part where fancy runs afoul of memory: I see myself looking down, holding a soda in one hand, noticing a GPS bracelet around his ankle. It doesn’t surprise me that I would have thought nothing of it: it was none of my business. In fact, it wasn’t anything I hadn’t seen before by then. I remember thinking, if he and I didn’t lead such busy lives, between the kids and work, maybe we could have even become friends. I admit, I did not inquire into what he did for a living.

A few weeks later I saw him in person, for the last time. I had the leisure to walk my kid to school in the morning because I had just lost my job. As we came up to the drop-off gate, S— waved, but he froze upon seeing the child-size cello case my kid was carrying like a backpack. Both he and A—’s daughter were taking lessons as part of the afterschool program, but S— had forgotten to bring her instrument that day. He explained he had to be somewhere and didn’t have time to retrieve it, so I volunteered to go back to A—’s apartment, which was in walking distance. No one would be home, he said, but he could lend me the key, if I would just tuck it under the doormat as I left. He was gracious, then jumped into a car waiting for him at the curb.

A— lived on the second floor of a walk-up. The front door opened into the living room where the birthday party had been held. There were indicators S— had already settled in, like men’s clothes lying around and an Xbox hooked up to the television. This was when, after a long-delayed reaction, the ankle monitor swam back into my consciousness. According to S—, the cello would be in the girl’s bedroom, where she practiced, down the narrow hall, second room to the right. I found it but did not bother to check if there was actually a cello inside, although the weight of it felt right.

The mirage of the bracelet was the first glimmer of chance, but everything snapped together as I stepped into the sunlight with the case slung over my shoulder, an image that contained in it anything from a small violoncello to money to drugs to an automatic rifle.

For there was no doubt I was being watched. The walk back to school collapsed into all that was to follow: the moment I turned on the evening news and saw “Uncle S—,” my son pointing at the screen; the terrifying movie in my head of the police closing in on A—’s apartment, knocking down the front door with guns pulled; the indictments that were handed down regarding funds from weapons sales that were directed to the coffers of the local politician’s campaign chest; the arrest of that politician. Looking back, it was just dirty pool, but I was naïve back then. Even as it became apparent a black sedan had been creeping behind me since I left the apartment, I would not consider the possibilities. For security reasons, I was not allowed to bring the cello directly to a classroom; I had to check it in at the office. The car that had been following me veered away.

Sometimes I hear news of A— or S—. I lead a different life now, one I consider a form of sleepwalking, and they belong to what seems to be the living world. I still keep up with other former friends, but there is a distance between us. I have no regrets, of course, but what I do miss from the old days, strange as it may seem, is the need for hope we all felt back then. That hunger, in hindsight, was what had kept me alive. Let me be clear: it is not why I stay in touch with them. That kind of despair, which is total, is not something I would wish on anybody, and certainly not on them, whom I consider more honorable than the crowd I associate with now. Instead, I am discreet about my needs, and for them, I can go elsewhere.

In Search of the Master

Once-vivid colors have faded into the façades and wooden shutters, a Havana or Kingston of the mind. A cat suns on a porch next to aquamarine murals, while a giant armless skeleton peeks over a leaning fence. We walk by a barky dog. A guitar shop armored in wire mesh fails to welcome us. We wait for the bus. The sun comes out.

There is croque monsieur, a slice of Gentilly cake, and a cup of bread pudding. An Expressionist oil painting hangs at waist-level under the counter, along with other bric-à-brac. We order the combo special, with its concentrated exotic flavors—is that peppercorn?—with a glass of Bordeaux, followed by pig ears and hush puppies. The flat-red-painted walls are the same tone as in the living room of our old home, the color of life or strife, bringing out the other bright colors of the paintings on the walls and in the fabric of the clothes of the clientele. A well-made drink should feel proper.

The avenue lined with plantation-style homes and oak trees passes by. In a first edition of Interview with the Vampire, right there on the first page, is a mention of Divisadero Street. The smell of new books mingles with that of old. They really do have hardcovers here. The woman at the register goes on about some writer who dropped by and was a creep, without mentioning his name, referring to the endless sex scenes involving the main character in his novel, obviously a thinly disguised fantasy persona. The book cover is the same shade of blue as the sofa, the vase, and the crystal stone.

The sky goes back to being overcast, but the day begins to warm. It is the winter solstice. Those Gothic letters are pristine over green shutters on the avenue. Under the freeway overpass, white herons bathe in stagnant puddles, accompanied by flies, crows, and squirrels. We come upon an intersection of a store with two entrances, one for the bakery and the other for chicken and waffles, flanked by two other takeout joints also selling fried chicken. That makes for three businesses competing for the same customer. Bullet holes aerate the window of the store with two entrances. A busted laundry machine lies out front. The driver waves us onto the bus, no need to pay the fare.

The houses of the quarter glow in the late afternoon sun. There is a panicked hunt for a drugstore, for Benadryl, and a supermarket, for French bread. We settle on a “pistol” from a sandwich shop. The weekend and warmth draw a younger crowd, white girls moving in packs, with crowns on their heads and beads off their shoulders. The stores close. The neighborhood transitions for the night shift.

This building was a former slave exchange, but now it’s some bar. Scenes are red-lit, that is, redolent of the Caribbean: spotlit mansions, balconies, their ghosts, and the flash and dazzle. A duo playing guitar and a bass made out of a stick and a bucket strung together have the local can-do spirit and knack for the off-kilter. They are joined by a clarinetist who sings out of the side of his hand and a trombonist. This is the American character: artwork in the serial-killer style, bottles, candles, yarn dolls, a tuba, a drum, the humor and vivacity in the face of death, the cardboard-cutout quality of many disparate things that do not fit. The singer doesn’t show when the bandleader calls her, and only when he is about to give up does she stroll to the stand with a kindergarten teacher’s bearing. Canned stage patter follows.

Books shelved on the windowsill in this floating hotel overlook a bay. Oh, the pace is slow here, with gulls and light ripples on the water. We sip surprisingly decent breakfast tea.

He looks up. He recognizes me, clearly. The concern was the words would not be forthcoming, but there are phrases that start off with the old flair and authority. They are only interrupted as he loses the thread. The most noticeable things are nonverbal: he enjoys the Ghirardelli chocolates as he pages through the copy of the book I brought with me. I point out that the writer had intended to publish it as unbound sheets. He keeps nodding while flipping the pages back and forth, with obvious pleasure, caressing the paper between his fingers.

“But the pagination …,” he says.

“What about the pagination?”

No response. The image presented is the back of his head, unmoving: a black box.

The city lies underwater, under flickering orange lights and the bent of history evoked by would-be Prousts of the tropics, Gaugins of the West Indies.

We are directed across the street to a bar if we need to use the restroom. An old woman in a mask steps across the street for a smoke. The night before the atmospheric river, we go in to watch moving ukiyo-e images on a screen, whose lines and primary colors in the dark vibrate to the heat of the city outside.

A rat scampers down the aisle. We stroll along the necropolis, hidden, but only partially, by crumbling walls. A car honks. At us? The old structures are worn but still intact, isolate and of unknown purpose. There are no signs. Next door is a purple gas station and a hand-painted board for fried chicken and fried rice, with tiny curled pink shrimp. It ends up tasting more Chinese than we thought it would.

About the Author

Alvin Lu’s new novel, Daydreamers, is forthcoming from Fiction Collective 2.

Alvin Lu’s new novel, Daydreamers, is forthcoming from Fiction Collective 2.

Prose

The Tangled Mysteries or The Transmutation of Affection Bruno Lloret, translated by Ellen Jones

Nova Veronica Wasson

Crying Spirit Kasimma

Diwata, Where She Walked Wilfrido Nolledo

Fake Moon Amy DeBellis

Zeppole (aka Awama) Khalil AbuSharekh

Excerpt from Imagine Breaking Everything Lina Munar Guevara, translated by Ellen Jones

Five Shots of Gay Sam, 2009-10 Daniel David Froid

Two Tales Alvin Lu

The Wall Ricardo Piglia, translated by Erik Noonan

Skinny Dipping Bailey Sims

Eight Quebecois Surnames Francisco García González translated by Bradley J. Nelson

Poetry

happy William Aarnes

i really love the little things that go unnoticed Philip Jason

College Jeffrey Kingman

The Desert Inn Betsy Martin

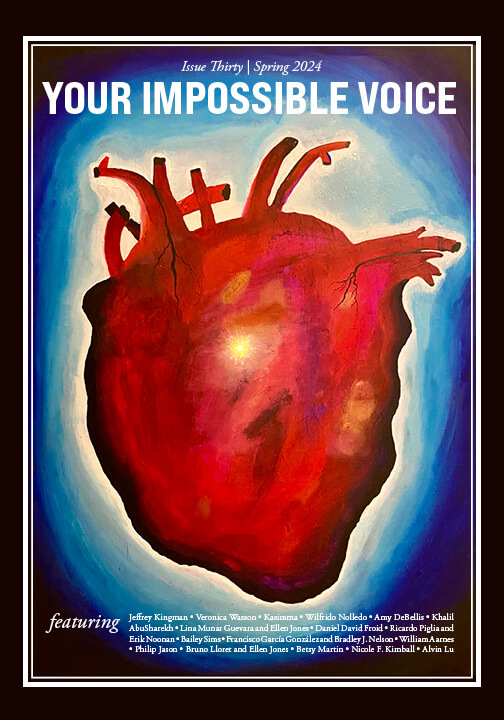

Cover Art

In the Heart of Love Nicole F. Kimball