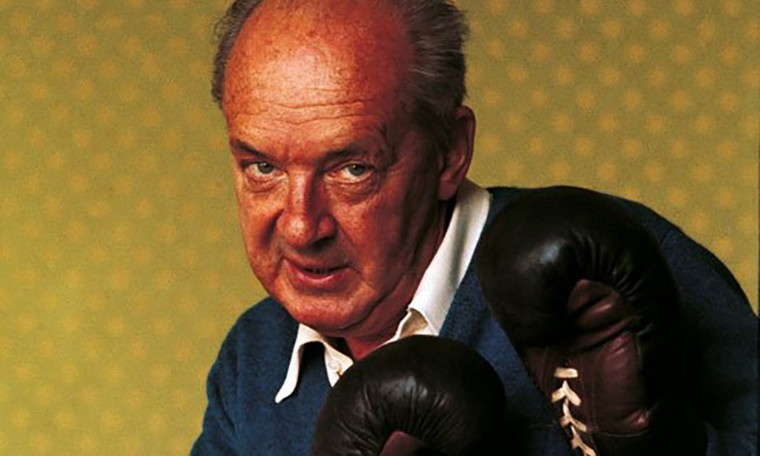

The Poetry of Astonishment: Rereading Garden Time

by W. S. MERWIN

By Wally Swist

I have been rereading Garden Time, W. S. Merwin’s latest collection and thought it best to share some notes about the book I made. Did you notice that there are no publication acknowledgments in the book? Merwin has come to a point where he doesn’t even need them. Although that is not particularly a sign of his being a master (along with such other of the finest American poets as Jack Gilbert), I do think it is worth mentioning. It seems that these 60-some poems are recent ones he had written and grouped them together for Copper Canyon to publish. I somehow admire that.

I wanted to list, as well, my favorite poems, and in some cases why they are such. I do recall doing something like this when I first read the book back in September 2017, upon its publication. However, I believe I might have failed to make some points. These points directly reference my reverence for Merwin’s poetry.

He, like no other I am aware of, is able to address eternal presence in his work. Days and years pass in his poems and then there is an activity, as in “Black Cherries” (“as I stand eating the black cherries/ from loaded branches above me/ saying to myself Remember this”), which brings us not only deeply into the expanding moment of consciousness but also regards the passage of time—as Rilke suggests—as no time. This aspect of Merwin’s writing is not one I have been aware of critics picking up on. However, this near fixation of Merwin, cosmically, in addressing the now moment, or eternal presence, is what also leads to his poetry literally resonating with what is mystic.

I have observed this since first starting reading Merwin, sometime in 1973. And I must say have always been taken with his focusing on themes of the mystic aspect of life but it has only been the last decade, or more, that I have observed his fascination with the eternal present. This also reflects my own day to day work and spiritual practices with attempting to maintain awareness of presence.

“Remembering Summer” is also one of these poems of timelessness Merwin has written to which we are indebted to him. However, “Rain at Daybreak” (“there is no other voice or other time”) and “Summer Sky” (“it is the same child now who watches the clouds change/ they appear from out of sight and change as the moment passes through them”) are poems that I love for all of the same reasons.

“Variations to the Accompaniment of a Cloud” may be the most accomplished poem in Garden Time. It is not my favorite, but it is worth mentioning Merwin’s craft and where he takes the poem to. Here we come, again, to a leitmotif of one and all: “my love was always/ woven with leaving/ moment by moment leaving/ the one time.” The conclusion of the poem expands to the point of being all inclusive as well as all conclusive. It is perhaps an example of Merwin’s understanding of the physics of spirituality–the Big Bang exploding in all of us and then the re-coalescing of the universe within us, as well.

“River” and “Loss” are fine poems, too: “River” because of “there” being “only one river/ that was always on its way;” and in “Loss” Merwin mourns his brother, who died shortly after birth, with once again Merwin conjuring the ringing of a mystic bell when he concludes the poem with: “all my life he has been near me/ but I cannot tell you anything/ about him.”

“The Other House” is also an example of Merwin’s fascination with presence, especially in the poem’s two concluding lines: “the house is the old house and I am here in the morning/ in the sunlight and the same bird is singing.” Emily Dickinson would have loved reading Merwin. The act of reading him not only takes the top of one’s head off but as in James Wright’s poem, “Blessing,” we actually “step out of [our] bodies” where “we [would]/ break into blossom.”

In “Wild Geese” Merwin sets the stage for our seeing and hearing the wild geese but he never describes their calls, so that we hear their cries even louder in our mind and then are left with the silence of their passing.

the vastness of all that has

been lost it is still there

when the poet in exile

looks up long ago hearing

the voices

of wild geese far above him flying home

My favorite poem in the book is “Still Water,” which epitomizes Merwin’s craft and his ability to render what is sacred in an immemorial poetry. The parallelism in the poem, as in the lines “through dreams of flying and forgetting/ and dreams of belonging and departing,” which also imparts a memorable lyrical quality within the poem, is really quite astonishing, as in lines quoted below, as he invokes the life of “clouds over the mountaintops” and how they devolve into a single pool:

taking along flakes of starlight

moonlight through dreams of

flying and forgetting and dreams

of belonging yet departing now it

lies at last by its green pasture

and cradles the stillness of an

empty sky this is the present it

was flowing toward this is the

face it can never see

The poetry of astonishment is what Merwin has achieved, especially in “Still Water.” If we haven’t been attuned in seeing our lives in such a manner then in reading W. S. Merwin we are able to become aware of more than a glimmer of the sacred and its flow and flux in our lives. In a poetry as revelation, or as a touchstone of satori, the kensho of seeing into our own true nature, results in our living life differently and more fully, more open to our being conscious, more open to our lives touching others with grace.

Perhaps the best way to conclude discussing Garden Time is in quoting one of the book’s short poems, since it is primarily a book of short poems, which appears toward the end of the book. My choice, and another favorite of mine, is the poem, entitled, “Voices over Water.” Another recurrent theme in Merwin’s poetry is that of past life, of our many reincarnations. We live in a society which is hardly mature spiritually to fully believe that we do have past lives, but for Merwin it is a working conception, one that is transformative and transforming.

“Voices over Water”

There are spirits that come

back to us when we have

grown into another age we

recognize them just as they

leave us

we remember them when we cannot

hear them some of them come from the

bodies of birds some arrive unnoticed as

forgetting

they do not recall earlier lives

and there are distant voices still hoping to find us

The poetry of Garden Time evokes those “spirits that come back to us/ when we have grown into another age.” When our age is as derelict and irresponsible spiritually, socially, and politically, as it currently is, it is a true boon to remember, on our worst days as well as our best, that there are voices which “arrive unnoticed as forgetting,” that whomever we are “there are distant voices still hoping to find us” for the sake of felicity, nourishment, and fulfillment—in recognizing this within ourselves as well in the lives of others.

Garden Time

W. S. Merwin

Copper Canyon Press

ISBN: 978-1556594991

About the Author

Media Credit: Matt Lin

Wally Swist has published over forty books and chapbooks of poetry and prose, including Huang Po and the Dimensions of Love (Southern Illinois University Press, 2012), selected by Yusef Komunyakaa as co-winner in the 2011 Crab Orchard Series Open Poetry Contest, and Daodejing: A New Interpretation (Lamar University Press, 2015).

His translations have been and/or will be published in Chiron Review, Ezra: An Online Journal of Translation, The RavensPerch: Adding Breadth to Words, Solace: A Magazine of Diverse Voices, Transference: A Literary Journal Featuring the Art & Process of Translation, (Western Michigan Department of Languages), and Woven Tale Press.

Recent books of poetry include A Bird Who Seems to Know Me: Poems Regarding Birds & Nature (Ex Ophidia Press, 2019), the winner of the 2018 Ex Ophidia Press Poetry Prize, The Bees of the Invisible (2019), Evanescence: Selected Poems (2020), and Awakening & Visitation (2020), with Shanti Arts. Forthcoming books include A Writer’s Statements on Beauty: New & Selected Essays & Reviews, Taking Residence, and a translation of Giuseppe Ungaretti’s L’Allegria/Cheerfulness, also with Shanti Arts.

He is also the author of Singing for Nothing: Selected Nonfiction as Literary Memoir (Operating System, 2018).