Review

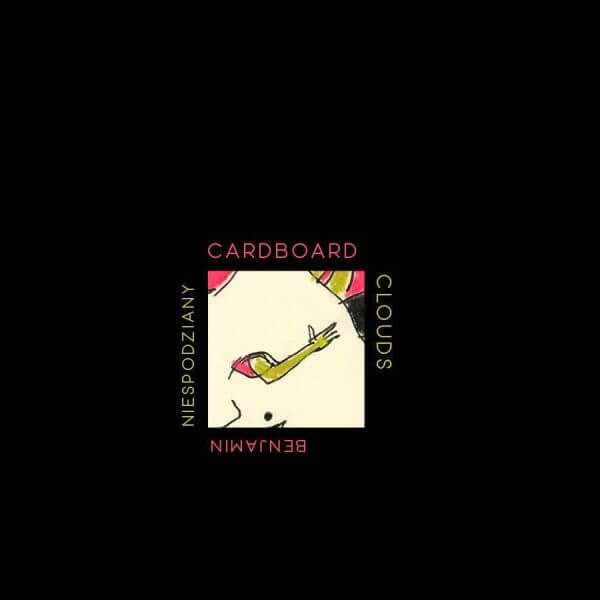

“The Curtain Does Not Draw”: Surrealism and Metafiction in Benjamin Niespodziany’s Cardboard Clouds

Publisher: X-R-A-Y Books

Review by Peter Kline

Benjamin Niespodziany’s ambitious and engaging new collection of prose poems, Cardboard Clouds, ushers readers into a world of madcap theater and casual danger where the curtain might rise on all manner of weather and monsters and fantastical impossibilities.

Two disparate artistic approaches underlie the book, surrealism, and postmodern metafiction. Hybridity is at its heart. While the book is a collection of prose poems, it’s framed as a series of one-act plays, complete with a cast of characters and (delightfully impossible!) staging directions. Each prose poem captures a single sequence of action “on stage” (or sometimes a variety of possible actions, often contradictory), generally including an account of the audience’s reaction to and interaction with the characters. Furthermore, the subtitle to the book calls it a “novella in one-act plays,” layering yet another genre on top of the first two. The book is less united by narrative throughline, however, than by the conceptual framework of the theater and the recurrence of characters, themes, events, and objects (props), the most prominent of these latter being the play’s eponymous “cardboard clouds,” which serve among other things as a symbol and persistent reminder of the staged non-reality of the world being displayed for the reader.

In order to get a sense of how surrealism and metafiction inform the experience of reading Cardboard Clouds, it’s useful to dig into some of the ideas underlying these movements. According to scholar Michael Richardson, surrealism “neither aims to subvert realism, as does the fantastic, nor does it try to transcend it. It looks for different means by which to explore reality itself.” André Breton developed surrealism as a way to give access to a “superior reality” that our life-long conditioning into a reason-based reality has occluded. Both of these writers point to the idea that true reality is more whimsical, unpredictable, and chaotic than most of us commonly suppose. Therefore, the bizarre non sequitur of the surrealist world, its typical disconnect from cause and effect of action and emotion, is not a commentary on reality but a vision of a truer reality than the one we have fooled ourselves into accepting.

Metafiction also interacts with a reader’s experience of reality, though in a different way. Metafiction calls attention to the constructed, literary fictionality of a text. Its interests tend to lie less with reality in our everyday lives or with some deeper reality beyond rational apprehension and more with the way art constructs a sense of reality. Like surrealism, though, its basic grounds of inquiry are the reader’s psychological experience with reality-making.

Each of these techniques is fundamentally self-conscious because of the way it deviates from both conventional narrative and reality-as-we-think-we-know-it. Rather than attempt to beguile readers into a sense that the world of the story is real, engrossing them with the illusion of the characters’ lives and struggles, surrealism and metafiction both foreground the mechanics of a text’s reality-making. Their pleasures therefore tend to be intellectual rather than emotional. The feelings they do evoke are more likely to be the intellectually-tinged emotions of delight, amusement, surprise, or uneasiness than deep pathos, joy, fear, or outrage.

Many elements of Cardboard Clouds have the effect of emphasizing the slippage between the real and surreal, life and performance. Within the overall framework of the theater, there are various other kinds of performance depicted – the magician, the politician, the salesman (each of whom in their way, I might add, are also engaged in shaping an audience’s sense of reality). Even audience reaction is framed as a kind of performance, with frequent references to the audience being given cues, sitcom-like, to react in particular ways to the action. And just like in an Elizabethan tragedy where many characters will die by the end of the play, these narrative sequences frequently involve the death of audience members (a surreal touch that again emphasizes the reality-making of the text).

Some of the most interesting moments of Cardboard Clouds arise from the uncomfortable overlap of surrealism and metafiction, as the reader is forced to negotiate the disparate effects of each technique on the story. One example of this occurs in the prose poem “Daisy Field,” which is brief enough that I can quote it in its entirety:

The stage is a field of daisies. The business man stands in the center with a cowboy hat full of water. He pours a little on each petal. Tenderly, patiently. He whistles a song. Some cast members scattered throughout the aisles cry a quiet cry. One cardboard cloud swings from up above. The business man looks up. “It was,” he tells the audience, “formerly a door.”

The surreal elements of this passage include the dreamlike sequence of a man watering flowers with a cowboy hat, and the emotional non sequitur of cast members crying in the audience. Its metafictional elements include the description of the stage as a “field of daisies,” which could either be a classical stage direction for the set designer of the implied production or a literal fact of the world of the story. These two systems of ideas come together most intriguingly in the final line. In the surreal world, a cloud might formerly be a door because objects can shift in ways that aren’t based in logic or science. The cloud might once have been a door and might soon be a kazoo, a sequence that ideally reveals a deeper logic to reality than the one we commonly perceive. In the metafictional world, the cloud might formerly be a door because the cardboard used for the cloud was once used to build a door on some other set. All art material is composed of bits and pieces of other art that has been reassembled for the purpose of creating a new illusion, a process that is foregrounded in metafiction. These two meanings create two fundamentally different ideas of reality and the story’s relationship with reality. The book does not privilege one of these over the other. The difficulty and delight of Cardboard Clouds lies in holding all of these meanings in mind simultaneously.

About the Author

Peter Kline is the author of two poetry collections, Mirrorforms (Parlor Press) and Deviants (SFASU Press). A former Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford University and James Merrill House and Amy Clampitt House resident, he teaches writing at the University of San Francisco and with Stanford’s Master of Liberal Arts Program. Since 2012 he has directed the San Francisco literary reading series Bazaar Writers Salon. He lives in San Francisco, and can be found online at www.peterklinepoetry.com.

Peter Kline is the author of two poetry collections, Mirrorforms (Parlor Press) and Deviants (SFASU Press). A former Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford University and James Merrill House and Amy Clampitt House resident, he teaches writing at the University of San Francisco and with Stanford’s Master of Liberal Arts Program. Since 2012 he has directed the San Francisco literary reading series Bazaar Writers Salon. He lives in San Francisco, and can be found online at www.peterklinepoetry.com.