Essay

Kokoro and the Endurance of the Human Spirit

by Wally Swist

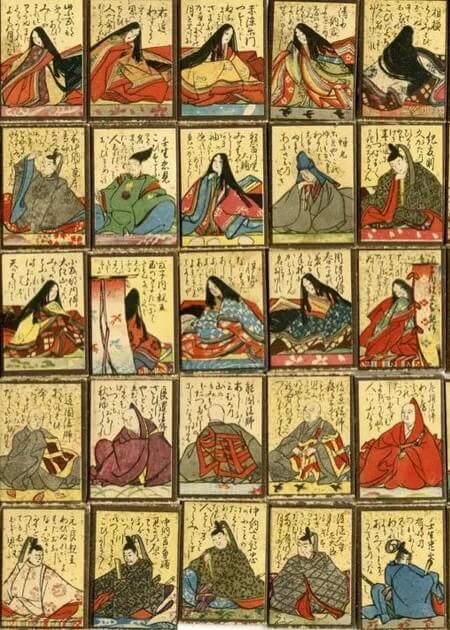

The Hyakunin Isshu can be translated as “one hundred poets (or people), one poem.” It is one of the several venerable anthologies of Japanese poetry. The Hyakunin was compiled by Fujiwara no Teika (1162-1241), and the first full-color edition was published in 1775. The poetry form is “waka” or “tanka.” The eminent woodblock artist Hokosai published his version of The Hyakunin at the height of this career in the early nineteenth century. Recently, I found Peter Morse’s book Hokosai: One Hundred Poets (NY: George Braziller, 1989), a small oblong folio, on a bookshelf in a wonderful antique shop, Antiques Collaborative, in Quechee, VT, and immediately fell in love with the book, purchased, it, and began to work with English translations from the original Japanese.

Hokosai published his version of The Hyakunin thirteen years before his death in 1836. The version was complete in representing all one hundred poems and poets; however, Peter Morse’s book, which is a gem of a book specifically as a reference for The Hyakunin and its excellent reproductions of Hokosai’s woodblock prints, does not contain eleven of the illustrations of the one hundred poems (numbers 15, 16, 29, 41, 46, 48, 54, 58, 66, 94, and 100). The reason for their absence is that those prints are either in private collections, as two of them are, and unavailable, or, as is the case for most of them, they are missing or lost.

The poems translated in Morse’s book were rendered by Clay MacCauley, whose translations were originally published in 1917. These translations were selected because, as Morse cites, MacCauley employed “a poetical form similar to that of the original – five-line unrhymed stanzas in a thirty-one syllable form.” Waka, or tanka, is composed in such a way as haiku is traditionally written in three lines of seven, five, and seven syllables in Japanese.

My translations are more concerned with the essence of each of the poems – while attempting to respect the brevity of the tanka form. Another significant aspect of the translation of The Hyakunin is the inclusion of crucial historical and social constructs, including place names, that are intrinsic to each poem. I experienced this challenge working with Professor Masako Takeda, who invited me to co-translate the thirty-two haiku that comprise “The Haiku Postcards of Aneyakouji Street,” which was a project initiated by a Japanese engineer, Shinpei Taniguchi, who was Secretary of The Anekakouji Neighborhood Association. Professor Takeda ensured Mr. Taniguchi that all socio-historical references and inflections would be incorporated into each haiku. Professor Takeda and I held firm in doing so in our translations that, after a decade of work, finally appeared as a feature in Modern Haiku.

I have attempted to do the same in my translations from The Hyakunin. Interestingly enough, one of my early influences, Kenneth Rexroth, also translated The Hyakunin. His translations appear in his seminal book One Hundred Poems from the Japanese (New York: New Directions, 1959). Unfortunately, however, Rexroth only translated some sixty-four of the one hundred poems deeming the rest of the work was too overtly weighed down in distinctly Japanese historical references and social inflection. So, these concerns prove to be obstacles, as Rexroth indicates, especially to “American readers.”

I will always admire and respect the Rexroth translations. Peter Morse also lists other note translations, including William N. Porter’s 1909 translation, which Morse claims is “handicapped” by a “rigid scheme of English rhymes and syllables” despite its spirit. However, Morse also mentions Kenneth Yasuda’s translation of The Hyakunin as “perhaps the finest among the complete translations” – Yasuda being also a significant contributor and pioneer of “the haiku in English” movement, especially for books such as A Pepper-Pod: Classic Japanese Poems together with Original Haiku (Alfred A. Knopf, 1947). Peter Morse also acknowledges that Tom Galt’s “recent work is exciting and imaginative” in another translation of The Hyakunin.

What is exhilarating about The Hyakunin is its portrayals of nature, love, and the passage of time – as major themes throughout the poems – which are exhilarating because of the uncanny combination of incisive brevity and profound resonance. Peter Morse offers that although he used the MacCauley translations of The Hyakunin, MacCauley’s work lacked what the Japanese call “heart” or kokoro. In my translations, I attempt to evoke exactly that: the kernel of kokoro in each poem while including as much inflection and reference as possible to the historical and social elements evoked in the original Japanese tanka.

The poetry written in The Hyakunin was originally compiled from a rather small group of imperial court poets who were largely related to each other eight hundred years ago by the eminent poet and anthologist Fujiwara no Teika. However, an essence and an aesthetic beauty pervade these “one hundred poems” by “one hundred poets” in uncanny ways that make them and their resonance resilient today. These poems remain compelling voices that speak to nature, love, and the astonishment of the human experience in witnessing the passage of time as much as anything written in the twenty-first century.

I am thankful for finding Peter Morse’s Hokosai: One Hundred Poets on a shelf in the fine Antiques Collaborative in Quechee, VT but even more grateful that I made the journey, as a translator, through these poems and found in them touchstones of what is human and what it is that endures the tests of time.

16.

Tachiwakare

Inaba no yama no

Mine ni oru

Matsutoshi kikaba

Ima kaeri kon

—Ariwara no Yukihira

If I leave

I will go to Inaba Mountain,

Where pines grow on its peak;

If I hear that you pine for me,

I will return to you straightaway.

100.

Momoshiki ya

Furuki nokiba no

Shinobu ni mo

Nao amari aru

Mukashi narikeri

—Emperor Juntoku

The incomparable palace!

Even in the shinobu grass

On its ancient eaves—

I discover a past in which

I long for yet ever more.

About the Author

Wally Swist’s books include Huang Po and the Dimensions of Love (Southern Illinois University Press, 2012), selected by Yusef Komunyakaa for the 2011 Crab Orchard Open Poetry Competition, A Bird Who Seems to Know Me: Poems Regarding Birds and Nature, winner of the 2018 Ex Ophidia Poetry Prize, Evanescence: Selected Poems (2020) and Taking Residence (2021), with Shanti Arts.

Wally Swist’s books include Huang Po and the Dimensions of Love (Southern Illinois University Press, 2012), selected by Yusef Komunyakaa for the 2011 Crab Orchard Open Poetry Competition, A Bird Who Seems to Know Me: Poems Regarding Birds and Nature, winner of the 2018 Ex Ophidia Poetry Prize, Evanescence: Selected Poems (2020) and Taking Residence (2021), with Shanti Arts.

His recent poetry and translations have appeared in Asymptote, Chicago Quarterly Review, Hunger Mountain: Vermont College of Fine Arts Journal, The Montreal Review, Pensive: A Global Journal of Spirituality and the Arts, Poetry London, Scoundrel Time, and The Seventh Quarry Poetry Magazine (Wales).

A Writer’s Statements on Beauty: New & Selected Essays & Reviews was published in 2022 by Shanti Arts. His translation of L’Allegria/Cheerfulness: Poems 1914-1919) by Giuseppe Ungaretti is forthcoming from Shanti Arts in 2023.