Issue 27 | Fall 2022

The Gorge

James Warner

I remember buying Guy Dieppe’s novel—at a bookstall beside the Seine, one spring afternoon—more clearly than I recall my first reading of it. It included some enjoyable phrases, which I now forget, but made no impression otherwise.

Months later, planning a vacation in Algeria, I recalled that Dieppe’s volume contained some piquant reflections on that land and was inspired to read it again.

But once I got underway, I began doubting I’d read the thing before after all. Its laconic tone I could recall, but not the storyline. And while plots are never quite as recollected, nothing here felt even remotely familiar. I wondered if I might somehow have picked up a different novel by Dieppe, or another draft of the same novel?

Dieppe writes in a notoriously meandering style, by way of paying mimetic homage to the meanderingness of reality, but this alone couldn’t explain my confusion. I was sure the protagonist, Quinasse, had worked for the Resistance—now he was clearly a Nazi collaborator. And none of these details about his work as a trouser machinist rang any bells.

Laying the book down on my nightstand, two thirds of my way through, the day before I headed south, I realized even the title had changed. It had been Shards of Light, printed in gilt lettering on the cover of a pristine first edition sewn and bound in cloth—the bouquiniste had assured me it was very rare. Now it was Oh City, Oh Travelers, and the book had become a trade paperback, thicker than a trade paperback can be and survive as many perusals as this one seemed to have undergone. Some pages had fallen out and been carefully reinserted with archival glue, others less carefully.

There were no references to Algeria.

Struggling with the implications, I slept poorly.

But the next morning, on my way to the Gare de Lyon, I began to comprehend. Dieppe put so much frenzied energy into rewriting his work that it continues to transform itself. This explains why reviewers who have only dipped into Dieppe describe his efforts so variously—as “a wry meditation on literary form,” “the last nouveau roman,” “Vietnamese social realism at its most anodyne,” and “vile apostasy and abomination without end,” to cite just a few critics foolish enough to classify a work so resistant to classification, one that constantly morphs into new iterations of itself.

I finished Oh City, Oh Travelers on the train to Marseilles. It ends with Quinasse and several of his mistresses journeying together to an unnamed place, by an unspecified means of transport, without any suggestion of closure. Trying to pin down what, if any, constant features might persist between readings, I embarked without hesitation on a third attempt, only to find that the pages were now unopened. I had to cut the folds at the top of the book myself with a letter-opener the conductor helpfully lent me. Dieppe’s restlessness so infected this book that it keeps regenerating itself, a forest that perennially changes. If in Oh City, Oh Travelers narrative structure was destabilized, Lost Thoughts—now the book’s title—struck me as too classical, and over-reliant on its own formal symmetry. It is written entirely in the past historic tense, and there are phrases Dieppe repeats so frequently—for example, “Perhaps it was from that day on that everything changed,” “the barest hint of a smile on her lips”—that they lose all meaning.

What Dieppe achieved, a project not lacking in audacity, was to write a book governed by the principles of indeterminacy, sufficiently self-undermining perpetually to refashion itself. Since Dieppe has no ideas to speak of, it is for this unprecedented, and I would even hazard unrepeatable, technical achievement that I imagine he will be remembered. Lost Thoughts takes place in its entirety at the Café de Flore in the year 1942, but once I started it over, it had another name and a distressingly hearty tone. Quinasse was now a mountaineer, and I found old bus tickets between the pages, and receipts from the Cinéma du Panthéon, along with enough dust to induce a minor coughing fit.

I did little in Marseilles but finalize the arrangements for my journey south and reread Dieppe. Books evolve over time, and the genre of Dieppe’s work shifts from reading to reading, sometimes fantastic or realist, sometimes surrealist or existentialist. Often Quinasse displays a sad tenderness, but other readings reveal him as a mere buffoon. There are almost always arguments between him and his mistresses about whether literature fundamentally distorts experience, arguments his mistresses invariably lose.

Although Dieppe has been compared to Perec and Modiano, he shares with these writers only a certain dreamlike abstraction and a profusion of characters marked by the shadows of their pasts. His status in the French literary hierarchy seems no more stable than his texts. Dining one evening in my hotel in Marseilles, within sight of the Château d’If, I leafed through a version in which Quinasse lives for a while on the brutal edge of society as a homeless person. This work appeared to have been published by Gallimard and to have won the Goncourt Prize—although the crinkly texture of the pages betrayed that at some point it had also been dropped in a bath. When I reached the end and reembarked, the novel was self-published under the title One Who Dares, with Dieppe styling himself a count on the title page.

The biographical sketches of Dieppe that sporadically appear are no more consistent—according to One Who Dares he is working on his next book, while the dust jacket of The Gascon Triplets claims he killed himself in the 1950s.

Can a book be considered a masterpiece if it can never, strictly speaking, be reread in its original form, that form being unfixed and unfathomable? The Gascon Triplets, brought out by a publisher I had never heard of, is such a masterpiece. On its frontispiece my copy was stamped as library property, never to be removed from the Bibliothèque Municipale de Saint-Étienne, which only enhanced my pleasure in reading it on the ferry to Algiers. Quinasse spends the book searching for one of his gloomiest mistresses, identified only as E. He visits the seaside, posing as an art dealer, never finds E., and near the end resolves to join the Foreign Legion.

Any text fluctuates in the minds of its readers, and the scenes we remember are never quite those that exist on the page. Quy Diep’s genius—as I crossed the Mediterranean the author became a Vietnamese woman who chooses to write in French—has been to take this process of authorial self-banishment yet further. Her retelling of the 1954 victory of the Viet Minh at Điện Biên Phủ is printed on rice paper, and inspired by the thesis that literature can be an instrument of battle. Morality is a Precondition for Popular Victory was the title now, with Quinasse appearing in a brief cameo as a drunken communications officer of the Sûreté, although in general Diep’s conviction that history is determined by economic forces rather than bourgeois individuals made it hard for me to distinguish her characters one from another.

“When my tour guide drove me up into the Atlas Mountains, the book was a satirical exposé of the corruption of local political elites, a roman à clef, which I was careful to keep out of sight.”

By the time I glimpsed the coast of Africa, Diep’s work was a zine, stapled together, a mini-memoir in the form of a graphic novella about a woman who travels from Hanoi to Paris, seeking freedom but finding only crushing loneliness. Some of the pictures were racy enough that the customs officer in Algiers threatened to confiscate it.

It took me days to clear Algerian customs, time to grow intimately acquainted with Diep’s oeuvre. Jean Echenoz has suggested that one must reread Proust first, before reading him—Diep, one is necessarily always rereading for the first time. Rereading may even be her central theme. While it is admittedly hard to pin down the subtexts of a work whose text is this amorphous, Diep seems to me to urge permanent resistance to establishment modes of thought. Her approach owes much to the great and ancient streams of the folk traditions of Vietnam, in which stories exist in multiple versions, supernatural beings abound, and the persona of the writer has traditionally receded into anonymity.

I perused Diep’s vertiginously variegated volume in Algerian tearooms, more obsessed by her words than by the tourists around me. Sometimes the pages were black, with occasional sketches of E. in luminous silver ink. The font was unfamiliar to me, and the pages did not flip crisply but rolled like fabric. Once Diep’s book was an advance review copy of a magical realist story collection about softshell turtles, with a manically detailed marketing plan emblazoned on the back. Once it was a bestseller, issued by Éditions Calmann-Lévy, about E.’s search for a secret space to hide within herself, annotated with heavily underlined, rather obtuse marginalia, apparently in my own handwriting.

When my tour guide drove me up into the Atlas Mountains, the book was a satirical exposé of the corruption of local political elites, a roman à clef, which I was careful to keep out of sight.

A point arrives with any volume where one’s memories of past rereadings threaten to overwhelm one’s anticipation of future ones—in the case of Diep, that point is always already in the past. None of us will ever have read the same Diep. She reminds us how smoothly we efface our own pasts, changing life strategies without admitting we have done so, one façade eclipsing another. “Waves come and go,” E. tells her interrogators, “but the ocean remains.”

Valuing obsession over perfection, Diep believes we are so protean as to have few enduring traits. Or does she rather warn us how easily the voices of the marginalized can be erased, her post-colonial vignettes proving that what is possible exceeds what is imaginable? What proportion of the change we live through do we fail to notice, simply because we are so adaptable? (rE.)sist(E.r) is poetry of witness, written in English, about microaggressions suffered by LGTBQIAP+ diasporic Vietnamese in Europe’s predominantly white LGBTQIAP+ spaces, all the profits to be donated to a fund to stamp out Orientalism and cultural appropriation worldwide. As a writer identifying with many different communities of struggle, quy diep—now printing their name in lower case and calling themselves “they”—strive to rid us of all preconceptions but their own.

(rE.)sist(E.r) concludes with E. getting a sex change in Marrakech. As I read this scene in the labyrinthine casbah of Constantine—which is perched on the edge of a deep gorge—I felt diep had found the perfect device to express their own genderfluidity. E.’s eventual orientation remains ambiguous.

The last poem in this chapbook, “Shouts of the Silenced,” I found overly didactic.

Flipping it over to start again, I saw with dismay that the binding was now decorated with inlaid moonstones and amethysts, making it too expensive to carry safely around the casbah. Qi Dhi’b was the author’s name now—translated from the Arabic, this means Emerging Wolf.

What I now held was a flagrantly heretical Arabic sacred text. I could not risk being seen with this in small-town Algeria. Bystanders were scowling at me, and I had no choice but to hasten to a nearby bridge, and hurl Dhi’b’s book into the gorge.

The wind flipped its pages round as it spun downward, floundering as if to embrace the cosmos—now it was a ship’s log, now a treatise on illusion, now an Intergovernmental Compendium of Unimplemented Recommendations—before gliding to its final resting place in the sulky depths of the Rhumel river.

About the Author

James Warner’s short fiction has appeared in ZYZZYVA, EPOCH, Georgia Review, Mid-American Review, Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, and elsewhere. His work also appeared in Your Impossible Voice #16. He now lives in Long Beach, California. Somewhat to his surprise, he is still busy being born.

James Warner’s short fiction has appeared in ZYZZYVA, EPOCH, Georgia Review, Mid-American Review, Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, and elsewhere. His work also appeared in Your Impossible Voice #16. He now lives in Long Beach, California. Somewhat to his surprise, he is still busy being born.

Prose

Nonie in Excelsis (Excerpt from About Ed) Robert Glück

Dirk Julia Kohli, translated by Rob Myatt

Panthera onca Jasleena Grewal

The Border Solomon Samson

Tikibik Dominic Blewett

Mistake or Accident Laurie Stone

Excerpt from Mice 1961 Stacey Levine

The Cathedral of Desire Nina Schuyler

The Gorge James Warner

In This Case, He Killed an Innocent Person Carla Bessa, translated by Elton Uliana

A Chinese Temple in California Alvin Lu

Poetry

you have become an archive. Lorelei Bacht

thunderclouds

On the Things I Did at the End of the World Beatriz Rocha, translated by Grant Schutzman

In this movie David C. Hall

Spot Rolla Barraq, translated by Muntather Alsawad and Jeffrey Clapp

Let There Exist For Us… Eva-Maria Sher

That I Would Cameron Morse

Surf

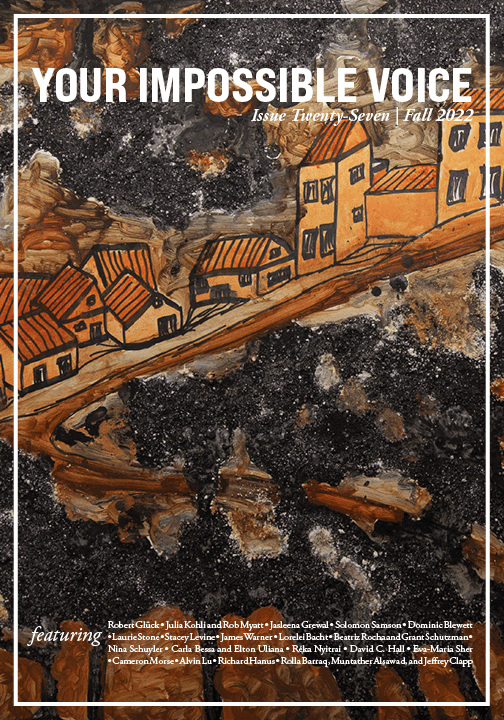

Cover Art

Image 001 Richard Hanus