By Art Beck

There’s a bumper sticker that I fondly remember from a writing residency in a secluded, artsy town: Port Townsend Washington. We’re all here because we’re not all there. I’m sure other little towns have probably used the slogan, although Port Townsend is the only place I’ve ever seen it. But it also occurs to me that the phrase might apply to nongeographic literary locales as well.

To wit—to those explorations labeled variously as “innovative,” “experimental,” “postmodern,” post narrative,” “post linear,” post-whatever fiction. Early December used to be my favorite time to book a cottage in the evergreens at Centrum in Port Townsend. But this year, I’m staying home in San Francisco and doing some late fall reading. And I find myself concurrently absorbing two very different short story collections that seem to have one thing in common. They both bring me to places it might otherwise never occur to me to explore, and the term “idiosyncratic” seems a defining characteristic of each.

•

I have to say I resisted entering Hampton’s territory. Her first few stories start by describing various ways a child might feel growing up not to feel. I found myself envisioning the dreams of an unplugged robot. An off-putting weirdness, intoned, say, by a sort of dour, asexual Sarah Silverman. The energy in the apathy—so where’s the fun in that?

In the opening story, “My Chute,” the protagonist begins:

I would go with my family to the museum and the restaurants, trying to find what I was supposed to love. The nudes were lovely, and I could see how a slab of marble retained the shape of a man, but I would just think how great it would be to have my own chute, a longish tube to push things through—anything, great or trash, it wouldn’t matter to me. I would push it all through my chute …

She begins by imagining the chute, but in the course of the narrative it takes on its own independent life. Initially an internal appendage of sorts, a dark, quiet place to hide. But then, it grows:

… teeth around its opening; a line of incisors and canines the size of mine. What is the purpose of teeth, if not to block an entrance? I suppose they are also for ripping and grinding. And they hint at speech—they make little walls for words to hide behind before they venture out.

And the chute also becomes useful for disposing of annoyances: “I could push my family through my chute—my chute was very accommodating. Whatever I wanted to lose, there my chute would be, moving like a worm, taking it from my hands, taking it away from me … ” Eventually, however, the chute grows out away from her, no longer in her control. In the end, she expects it to soon reach a “point that is dimensionless.”

Throughout the narrative, Hampton’s chute becomes a more and more interesting—metaphorical?—device. The problem for the reader—or at least for me—is that you keep getting hung up on what kind of personality is imagining these things and why you should care about this protagonist.

My old Polish grandmother used to have a cautionary saying, “Keep your tongue behind your teeth.” There’s a similar dynamic here with the “chute.” But my young immigrant grandmother was navigating her way through the social-services minefield of Depression-era Chicago with five kids, and a husband in the insane asylum. The alienation Hampton is describing seems of a more self-referential sort. The kind that makes you want to say, “Snap out of it, why don’t you?”

Or, is there something the reader needs to snap out of? If you want to read Hampton on her own terms and enjoy the work for its own intent, maybe you have to leave the baggage of character and personality behind and focus primarily on imagery and conjecture the way, say a physicist might play with equations.

In “Nowhere Hill,” a child protagonist sees another child wearing a watch and decides to hide her own watch in her pocket, “where the other children could not see it, and, not seeing it, couldn’t break it or take it away from me.” The watch begins to feel “like a heaviness” in her “clothing, like sweat, and while I was aware of the heaviness that wasn’t sweat, yet felt like sweat, the heaviness wasn’t uncomfortable. Yet it didn’t bother me until I began to think I could detect an odor coming from the heaviness.”

As the narrative progresses, we learn that the watch is a Mickey Mouse watch and the sweaty odor seems to be coming from Mickey’s gloved hands on the dial.

I looked at the watch.

I looked at Mickey’s skinny arms on the dial which I now hated because they were connected to the hands that were sweating inside those gloves, which stank, and whose odor had contaminated my clothing and now everything outside of my clothing …

At around this point, I found myself going back to the story’s opening paragraph:

There was a particular place in a particular park where a person could stand, at a certain time, on a certain day, and cast no shadow.

The children in the story are all racing to reach the top of that “Nowhere Hill.” Something clicked for me, then. I took my “psychological” filter off and began to look at the narrative as a sort of extended sundial metaphor on time. With physical, rather than “character,” imagery. At the end, a tall boy reaches the spot where he “casts no shadow,” then leads the other children down the hill as they count down aloud, “eleven, ten, nine … ” The boy, it seems, only begins to lose his shadow at the magic spot, but will completely have no shadow when they reach zero. The story ends with the protagonist standing at the bottom of the hill.

… and when they said zero, the number that meant nothing at all, I threw the watch as far as I could in a direction I would never go to retrieve it. I threw the hideous creature in the horribly big gloves and I didn’t care whether they were white or yellow or whether he cast a shadow as he got farther from me and I got farther from Nowhere Hill.

So, I stopped trying to struggle with what made the narrator(s) click, and just let myself wander the elusive virtual-logic of Hampton’s language; i.e., I allowed myself to indulge her prose the way I’d indulge a certain kind of postmodern atonal poem, say, by Laura Moriarty or Lyn Hejinian. In “Interruptions,” the narrator, describing a conversation with her sister, offers:

Another train is in her voice. I think of the straight tracks in her voice, and of the more complicated places where the tracks curve and overlap …

Never mind she says. I know you’re busy.

But still, she says.

It’s a long train that passes.

I’m still not used to these interruptions, she says.

I think of steel curving in the darkness.

Or, in “Lookout”:

I wander through corporate infrastructure toward the river. The parking lots are empty, yet fluorescence continues to brighten their intensity almost to its landscaped edges, where differences between nature and artifice are obscured by a darkness that is more like an absence of fluorescence than its own presence.

Hampton is clearly writing prose, but it’s “absences,” I think, rather than what’s present, that she, more often than not, finds herself attempting to navigate or describe. And this seems to me akin to a kind of discipline of non-statement that often characterizes certain contemporary poetry.

Even, in some of Hampton’s more “present” narratives, that kinship seems to hold. Take Leslie Scalapino’s poem “Isn’t it interesting how a woman like me/ pursues in man after man” (from Hmmmm):

… i.e. When in bed, the man said,/ while calling her pet names by whistling, he liked to nip her/ with his lips. And once, during intercourse, when he told her/ what he would like most from her, the man said facetiously:/ I want you to say the word yip, as in the yelp of a young dog.

Here’s Hampton in a passage from “Mole”:

… This boyfriend also wanted me to make certain sounds over and over. He found a mantra online that he said would have aphrodisiac effects. I made the sounds every night hundreds of times. I just want to go to sleep, I finally said.

Since sleep is a nighttime alternative to sex, I have done a lot of sleeping, and in my sleeping, a lot of dreaming. But dreams do not feel like other people. I keep running and running through those trees, not knowing why they’re all dead, and in the morning, when I wake beside another person, I am uncertain what, and how much of it, can be said.

In fact, Scalapino’s early-career The Woman Who Could Read the Minds of Dogs (in which the above poem appears) makes a good bookcase companion to Hampton’s Discomfort. Both are written from the edges, both intone within the idiosyncratic lyric of their own skins.

Similarly, “Cassidy,” an expressive piece near the end of the collection, might easily have found publication in a journal of innovative poetry. Cassidy is a mysterious male entity, more spirit than physical (evocative perhaps of a Jungian animus?). “At night, the air waits for Cassidy the way it does for a fuse to free its load. Then the great burst air gets to be, the blues and pinks and falling greens of fleur-de-lis the stars might have made when stars were as young as Cassidy … ” But there are barriers between the narrator and Cassidy. For one, “the screen in the door that keeps bugs between us … though something’s eating through the screen … ”

… How young is Cassidy? When ice on the lake breaks in spring, when anything breaks in spring, Cassidy is released from something green that I know has been waiting for me, and it is a fear-feeling and it floats in the dust in the mirror after I haven’t eaten breakfast again …

The ephemeral Cassidy seems to be bringing someone or something to her:

… -evidence of this is easy to find in drawers not often looked in: those aren’t my clothes and they aren’t his; who is it then who lives?

I think I hear this other person sometimes.

I watch a woman where a window comes to drink.

I taste a surrounding mouth with mine.

At night, I am parted by the sides of something—something comes to drink from the birds that rustle softly in my chest.

In the gaps between my teeth, I see tiny other teeth.

I hear them blink. I let them eat …

Finally, Cassidy arrives, entering through a “chewed-through screen,” “carrying something heavy”:

I let him lay her in my bed, her head where my feet would be. Her feet are very clean, but her bare head appears to have been walking for a long time. There are leaves and dirt in her hair and they fall onto the sheet. When she asks for a glass of water, I bring her the one I drink from.

Cassidy has gone outside to leave. He isn’t gone yet.

Where the path enters the trees, where light enters and leaves, his white shirt comes back for something I can’t reach.

Discomfort won’t be everyone’s cup of tea. It’s not so much that nothing much really happens in the stories. The successful short story can be as much about mood as narrative. But where it’s not redeemed by lyricism, the off-kilter mood of some of these pieces can tend toward the exclusionary, unlike, say, the simpatico strangeness of a Murakami. That said, there’s a distinct audience for what might be loosely styled West Coast language poetry, and I think many of these readers will be quite simpatico with Hampton’s prose.

•

Hampton’s bio notes an MFA from the Brown writing program, and the back cover of Discomfort has supportive blurbs from writer/teachers Carole Maso, Brian Evenson, and Stacey Levine. Although Drummond, in his younger days, earned a master’s in creative writing at CCNY, he makes his living as a criminal defense attorney in Oklahoma and Texas.

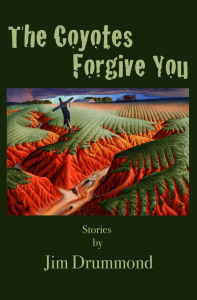

And his back cover blurbs are from “Richard Nixon,” “Wallace Stevens,” “U.S. Grant,” “John Milton,” “William Blake,” “Vincent Van Gogh,” and “Iron John.”

There’s actually some method here. Each of the blurbs refers to a different particular story. The book’s first story, “The Insureds,” is a shaggy dog joke told by an insurance adjustor to a couple of old rural claimants. A back cover “Wallace Stevens” blurb reads, “Jim’s deep, near-surreal grasp of insurance is pure poetry. He sees with Le Monocle de Mon Oncle.”

There may also be a more subtle integrative intent with the front cover which bears a resonant reproduction of the Oklahoma artist Alexandre Hogue’s dustbowl painting, The Crucified Land. The protagonist in two of the stories is a painter named Cline. In “The Battle of the Washita,” we first see him as a boy living with his parents in a shantytown camp in Oklahoma and teaching himself to draw. One day, he goes “down to the river to fish and draw” and espies his mother on “a little raft tied to a stump” copulating with their landlord, Walter Bruce, on a quilt.

I was eleven, it was 1954, and the rope I swung through the trees on was the rope of Mom and Dad. The strands were so wrong here, but even I could see that the strands were also very strong. When two fuck and one doesn’t care, the face of that one is a lie. It’s a lie set on top of the body like the head of a dumb comedian on the body of David or the Thinker. Not here. Her face was a true story, and so was Walter Bruce’s and you could see right there that neither had a hold on the other. It was a wonder and horror I didn’t know what to do with. Dad should shoot him, she should kill herself, they should vanish together in their reflections on the river. I hated, without knowing why, all three, but also, I adored them.

The paragraph bears the insights of an author who, I presume, has a more than passing professional familiarity with the roots of mayhem; reading it you begin to wonder what terrible place this might be heading to. But the imagery is also coming from a narrator who we’re told will grow up to be an acclaimed painter. Drummond’s destination is elsewhere. The boy makes a sketch of what he saw and writes in block letters on it, “DAD. I’LL HELP YOU KILL MOM.”

His father, an itinerant oilfield roughneck, just says, “Get your things … You and I are going on.” The boy is shocked: “You’re not going to kill them?”

Instead, they travel the oilfields, camping in their truck, living hand to mouth. Finally, Frank, the father, gets enough money together to pay “a woman named Margaret” to keep him during the week so he could go to school. “Fridays, he’d come for me, beer faint on his breath, but there, wordless, but there … ”

Then one day, the havoc finally happens. His mother shows up at Cline’s classroom. Wearing a bandanna over her face, and brandishing a cap gun, she kidnaps him. Unlike the realism of the seminal scene at the river, the climax spins into an unlikely psychological scenario. Anne, Cline’s mother, tempts the boy into willingly accompanying her with a tale of a home she’s prepared for them. “I have everything, the car, the house, a job, a much better man, a garden, all the books, the records, a tv you can watch every night after your homework … ” The fledgling artist-child who’s been forced to “draw on grocery sacks” is more than tempted to choose “gold leaf and caviar” over “okra and pigs feet.”

But all this was a ploy. She pulls into an old roadside picnic area and begins to undress, while expounding about her “needs” and all the reasons she has no intention of letting him come home with her to complicate her new life. What she wants—the reason she’s kidnapped him—is to have him paint her naked. “Lets get out … Paint me now.”

Writing this, something occurred to me that I’d missed on my first read of the story. What was Cline going to paint her with, or on? Did she bring canvas and paints in the car? So, I closely reread the episode and found no mention of this. No matter, it’s in line with the sudden cartoonish unreality of Anne’s character and the less than likely mother-son interaction. Details would just defeat the illusion. A number of the stories in The Coyotes Forgive You have a science-fiction or fantasy bent, so it’s easy enough to just accept that we’ve slipped into an alternate reality here.

That surreal sense is also implicit in the adult Cline’s musing as he narrates the childhood scene:

When the truth flows out of you in paint and pencil strokes, you realize that as a liquid it does not necessarily place loyalty as a high virtue … just like paint when you touch it … Truth holds no images; does not last, because it needs to be liquid in the moment to be truth … you want truth’s water to hold, you mix it with some earth, and that’s paint, ink on the page …

… I did paint her. I tried to paint her doing a thousand things at once. Listening to Brenda Lee on the radio, washing laundry in the river like a figure from Bible tales … being covered on the raft by Walter Bruce, laughing at one of Frank’s airy meringue tales in spite of herself, the way she sat like a stone and cut space like a leopard …

The result is a culminating image:

… a statue of Unfairness, hearts eaten out. Her face was thin and hard set with her will. You did not think of angels, though she was purer than many who evoke them. She was not so thin on closer look. She tended to be voluptuous in the teeth of her hardness … but thin as Lincoln, all bones and long flat muscles …

… An eleven year old sat and painted her as would Matisse or Degas, and lost himself in it … he painted her like she was a bee or cloud or road …

Cline isn’t Alexandre Hogue. The dates are wrong, the scene of the boy’s painting is a ’50s rest stop strewn with picnic litter and planted in Bermuda grass, not a dustbowl farm. But given the Hogue cover painting and the Oklahoma setting, it’s hard to see how the painting described above could fail to evoke Hogue’s iconic Mother Earth Laid Bare in anyone at all familiar with his work. In any case, the climax finally discharged by the “Chekhovian pistol” of the river scene becomes, unexpectedly, one of aesthetic statement, rather than character, narrative, or even mood.

•

These are very different collections, in almost every way. Hampton, for a start, is urban-suburban. Her aesthetic aims at subtlety and finding the right words for the barely expressible. The stories in Discomfort are like facets of an elusive single feeling you’d like to shake free of but can’t because you can’t quite grasp what it is you’re feeling.

The Coyotes Forgive You doesn’t operate with that kind of intent. It’s a kaleidoscope of mostly unrelated forays—the way, maybe, someone might strike out in various directions trying to quench a thirst in the desert. Sometimes, as in “Confessor” (a tale of young guilty tragedy and shamanic atonement) or “Grant Says NO” (based on U.S. Grant’s post-presidential trip to Japan), Drummond sinks deep, clear wells.

That said, not all of Drummond’s readers will like all of his stories; he’s too multifaceted for that. “The Battle of the Washita,” discussed above, seems a good example of Drummond successfully tapping a fabulist underground stream. But some of his science-fiction wanderings, including several gender-bending speculations, while intellectually interesting, will appeal primarily to readers of a more cerebral bent. And then he throws in short pieces that seem primarily designed to keep you from taking him too seriously. A tic that might take some, but not me, aback. In this vein, the back cover blurb from “Vincent Van Gogh” reads, “Cline has my ear.”

On balance, all this seems fine. If there’s a certain, intentional rusticity here, it’s more akin to, say, Flannery O’Connor than Lake Wobegon. Drummond’s collection, taken as a whole, left me with the satisfaction of a baseball game, won by a mixture of small ball, patience, and strategically placed home runs that detonated out of a need to be hit. If some may perceive a few home team errors, they just add to the suspense.

As can be seen, Hampton and Drummond will interest very different audiences, and very different editors. I’m not even sure either author would enjoy the other. But what struck me were similarities in the mission statements of their respective publishers.

The Coyotes Forgive You is published by Mongrel Empire Press, an Oklahoma house specializing in local fiction and poetry. But, apart from that, they “are particularly interested in works that, because of their mixed generic, disciplinary, and philosophical approaches, cannot find a home at other presses which have a more narrowly defined mission.”

Ellipsis Press, which brought out Hampton, is “ … interested in innovative writers who have studied the traditional elements of the novel and skillfully experimented with these to emotionally moving and extraordinary ends. We like novels that look normal but aren’t (more than those that look weird but are actually quite normal), those that are successful at bypassing or evolving the necessary but often tired elements of character and/or plot, and those that respond in some way to the history of the novel as a genre and form.”

The sharp drop in publishing costs brought about by the digital age seems to have resulted in a proliferation of alternative presses, many with mission statements similar to the above. Does this translate into a proliferation of opportunity for writers of innovative fiction? Well, not necessarily—at least in the way, say, a proliferation of new popular genre publishers might. Formulaic genre is pretty much formulaic across the board. But despite their similar mission statements, I doubt Drummond would resonate with Ellipsis or Hampton with Mongrel Empire.

Do alternative presses presuppose alternative audiences? If so, idiosyncratic writers still need to search out their own, uniquely not-all-there publisher.

Discomfort

By Evelyn Hampton

Ellipsis Press (Jackson Heights, New York, 2014)

ISBN 9781940400

The Coyotes Forgive You

By Jim Drummond

Mongrel Empire Press (Norman, Oklahoma, 2011)

ISBN 9780983305217