By Mara Naselli

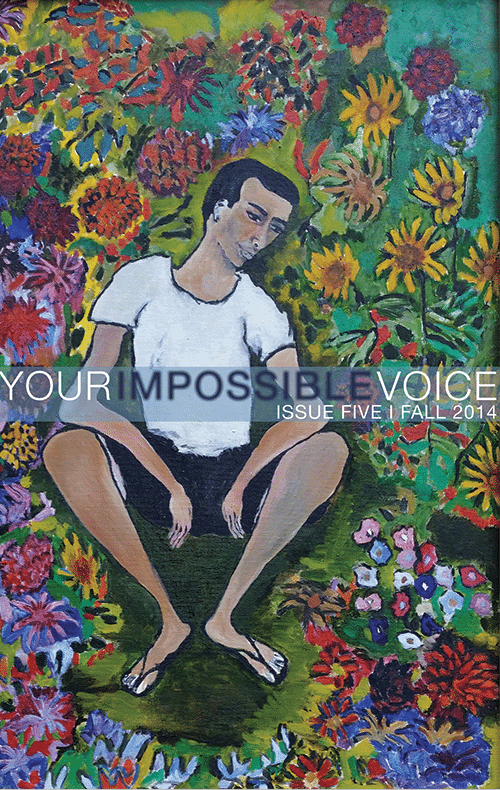

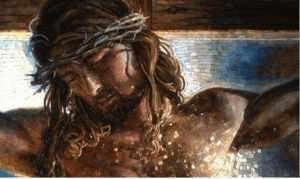

Crucifixion by Mia Tavonatti

At ArtPrize, the largest art competition in the world, a crowd had gathered just inside the DeVos Convention Center in Grand Rapids, Michigan. The quality of the light on this particular September afternoon in 2011 shone abrasively, even straining. The beams and wires of the stadium-like structure cast a grid of shadows in the space. The crowd was looking at art. There was Serenity Lake, a larger-than-life sculpture of a girl draped over a beach ball. There was a massive eight-paneled drawing of a man, his head thrown back and his eyes closed, as something resembling smoke came out of his ears, and the heads of Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, and Liszt floated around him. There was also Cascade, a twenty-foot ribbon of CDs hanging just outside the front entrance, a spill of multicolored polycarbonate iridescence. The crowd, though, was looking at Crucifixion, a large glass mosaic altarpiece. Orange and mauve clouds broke in the background of the scene. The Savior’s belly and thighs were roundly muscled, his hair blond and soft. People took pictures and texted their votes. Each individual piece of glass sparkled. Viewers were calling it “beautiful,” “gorgeous,” and “real.” Children rushed to it with the pleasure of recognition. “Look, Mommy! It’s Jesus on the cross!”

The spirit of ArtPrize is democratic. Anyone with fifty dollars and a work of art can enter to be selected by a venue. Each year since the contest started in 2009, the organizers have adjusted the rules and program slightly, but they have hewed to a simple idea: bring art to the public and let the public judge the art. In the art world, this is a radical idea. ArtPrize basically works like this: More than 150 venues in downtown Grand Rapids volunteer to display art during the contest. Venues range from art museums to office buildings to public parks to tattoo parlors. This year, about 1500 artists submitted artwork to be displayed. From the massive pool of entrants, the venues choose works of art. If it’s radical that anyone can enter, that anyone can display art, and that anyone can win first prize, even more radical is that anyone can be a judge. Winners are chosen by popular vote. The first round of voting determines the top ten. The next round determines the winner. For the first three years of the contest, 2009 to 2011, first prize was $250,000.

I watched with some anxiety to see how the public at large would judge such a wide field. It would be embarrassing if Grand Rapids, where I had just moved, voted to award a quarter of a million dollars for Nessie, a giant foam sculpture of a Loch Ness monster, mounted in the middle of the Grand River. Or a giant moose made out of nails. But I was also energized by the idea of it all. If you are going to have a democratic art contest, then you have to welcome everyone to the table. Just as we aspire to include everyone in our democratic political space. ArtPrize was asking not experts, but the people, to determine by what criteria we would evaluate the artwork, and to make a choice.

And wasn’t there something admirable in dreaming up and constructing a giant motorized roller skate? ArtPrize, I was beginning to think, had the potential to be more than an art contest. It could be an experiment in civic discourse. In 2011, public political and civic culture in the United States was on its way to deteriorating into acrimony and obstructionism. As a country, we had failed to talk about politics, failed to talk about religion, failed to talk about the poor and gun control and torture and education and any number of other issues that divide the country. Perhaps in this unlikely setting — a conservative Midwestern town — we could find some conversational inroads, some common ground. Surely, I thought, we could talk about art.

In 2010, in a community news forum, I wrote about these very things — about how bad art should be welcome, about how we can rise to the occasion to be articulate, practice good judgment, and elevate the conversation. I celebrated truly excellent works, but I criticized the big winners, too. The first prize in 2010 had been a gigantic pencil drawing copy of a military photograph. Second place had been a massive melodramatic mosaic.

In truth, my critique of the second place winner, Mia Tavonatti’s Svetlata, was only a few passing words. I am not a fan of snark, but my comments were just that. What was there to say? It was a larger-than-life blonde female figure clinging to a rock in a tide pool with surf and drapery swirling around her. I didn’t really give it a second thought. Until ArtPrize 2011. Mia Tavonatti was back. This time with a gigantic mosaic of Jesus. Svelata was irksome. Crucifixion was different. When I first saw it, I felt rage.

Why rage? Why not bemusement? The blimp-sized pig with wings was ridiculous, but innocent. The pride of lions welded out of nails was boring, not incendiary. The toothpick mermaid sculpture was just creepy. Almost from the start, the conversation around ArtPrize inspired a debate between those who professed to know something about art and those who had fun looking at weird, mostly enormous stuff. The elite view was that the flying pig and the like were not art, they were spectacle, and so they shouldn’t even be eligible to win. The populist view was, basically, who do you think you are telling us what’s art?

I was embarrassed by my rage. It betrayed my immoderate seriousness. So what if so many people loved Crucifixion? I didn’t like its complacency. I didn’t like that it didn’t show me a new way to look. I didn’t like that it merged religion with escapism and fantasy. I didn’t like its overrepresentation. I didn’t like that it smacked of strategy. Surely it must have occurred to Tavonatti that if, in this super-Christian town, a shimmering, helpless woman gripping a rock could get second place one year, a shimmering hunky Jesus could get first place the next. That’s not art, it’s market research. But why did it make me so mad?

Maybe I was missing something. Maybe my strong emotional response was obliterating any opportunity for me to see what those who loved it saw. These were, effectively, my new neighbors. What did it mean to them? What question did it answer? Maybe the piece could offer some insight. Maybe my rage could turn into understanding, even compassion, occasion the very discourse I was looking for. I just needed to ask the right questions and listen to the answers. What did those who admired the mosaic see in it? Clearly it was speaking to people. Churches were supposedly organizing bus trips to see it. There was always a crowd. And though it was impossible to get a good photograph of it — the blaring sunlight reflected a cataract of glare off the glass — viewers photographed it anyway, as if they were photographing a relic.

Crucifixion weighs 425 pounds, measures 9 feet by 13, and is mounted on a wood-backed frame, arced at the top like a stained-glass window. It hung from two cables in the convention center. Tavonatti would joke that was probably the only wall in town strong enough to hold Jesus. Each piece of glass in Crucifixion was hand-cut from stained glass and laid to fit. The glass was set in such a way that it appeared to swirl, gather, and expand over the contours of the design. The surface had a hand-hewn quality — smooth but irregular. No one could touch it, but it made you want to. Her labor was evident. Light bounced off each piece making it glitter. I looked and chatted with onlookers as I waited for Tavonatti. I had asked her for an interview by email. To my surprise, she readily agreed. About a week of voting remained before the winners would be announced. Tavonatti, it turned out, was always open to meet and talk. In advance of our first meeting, I told myself I might find a way to introduce my inquiry delicately, so delicately in fact, that the meaning would be evident without actual words being said. Because how would I manage to talk to Tavonatti about her work without betraying how much I hated it? Somehow I would let her know that while we might not be in the same aesthetic camp, I wanted to understand her approach, her vision, the execution of her work. That was the plan, anyway. “She’s very warm with the people,” someone said as I waited.

The altarpiece was commissioned, just after Tavonatti’s second-place win the year before, by St. Kilian Catholic Church in Orange County, California. When the construction of the church was delayed, Tavonatti decided to enter the piece in ArtPrize 2011. Her artist’s statement summarized how she put together the image. The photographs of her model were taken in a redwood forest near Santa Cruz. The wood beams used to construct the cross came from Home Depot. The wreath used to make the crown of thorns came from Michaels. It took 2500 hours to make. She drove it 2300 miles alone in a Penske truck from her home and studio in California to Michigan.

I overheard many viewers say how real he looked. But what struck me was how unreal her Jesus looked, how clean and tan and sculpted. I thought back on a portrait of Jesus by Fra Angelico I had seen at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York a few years back. Jesus’ head was painted with the gaunt angularity of Byzantine icons, circled in a corona of gold with only blue blankness behind him. But his eyes, shot through with red, arrested me. It was the intensity of the red — not a maroon or brown red, but a bright, oxygenated blood red. Fresh. The blood of exertion. There was no escape from its pain.

When I asked one woman what she thought of the piece as she stood looking at it, she smiled. “I wonder what point this was in the crucifixion,” she said. “We know at one point it went black.” It hadn’t occurred to me to think of it as a documentary. I tried to imagine what it might be like to see this Jesus as a kind of proof, an expression of complete belief.

Unlike many early representations of Christ that emphasize his humanity — picturing him with the thieves, for example — this one was otherworldly. The bottom of the cross cut a high contrast to the white clouds behind it. I tried to set aside my agnostic theological assumptions, but I was realizing they were at the core of my rage. Wasn’t the very point of Jesus as God that he was human? That God is in the ugliness of the everyday? God, if he/she/it exists at all, I thought, doesn’t want you drunk on beauty, or to give you some escape from the animal injustice of humanity. God does not speak to me, but if he/she/it did, I suspect God would want me to face everything I hate and find a way to love it anyway. Trying to keep the conversation going with the woman, I felt my voice slip into hesitation. I wanted to question her documentary assumptions further. “It’s interesting,” I said, “that the cross floats.” She nodded.

I directed my eavesdropping elsewhere. My journalistic strategy was oblique. What made me more uncomfortable? The prospect of speaking to Mia Tavonatti or speaking with her fans? DeVos Convention Center was not known for curating good art. If you were standing in front of Crucifixion, you were either at the Gordon Food Service convention on your way to the Safari of Flavor session or you had heard about the big picture of Jesus and come to admire it.

I overheard another reality comment — “right down to the nail in the foot.” Another man said, “It brings home what Christ has gone through, what he has done for each of us.”

I tried to see what he saw. I couldn’t. This Christ did not suffer. His smooth athletic body was poised. Gravity had not exercised its gruesome pull. The blood was rendered in a couple strands of glass, disappearing into the metatarsal of the foot or into the grain of wood below the hands. He gazed downward without a trace of pain. The clouds behind the cross looked as if they were breaking open, and behind the darkness was an orange-mauve light. Jesus’ loincloth was tied at the hip, and the excess unfurled like a billowing drape; its shadow echoed the pink and purple sky above the cross. The cross itself was ungrounded, as if we were witnessing a revisionist interpretation of the resurrection itself, in which the body and the cross, nailed together, rise up into the heavens. The composition of the cross, the clouds, and the loincloth undeniably drive the eye to Christ’s sex.

Mia Tavonatti arrived at the convention center carrying a box of postcards that promoted her piece. The day before, I had taken the last one. It had a detail of Jesus’ head on it, with Tavonatti’s foundation and business websites, and the number to text a vote for her. Her long black crocheted cardigan swished around her legs. Her blonde hair was cut in free-flowing layers. She tipped the box onto the floor and took off her silver aviator sunglasses. Her eyes were tired. “Seventeen thousand of these,” she said. Immediately people circled around her.

“That must have been nerve-wracking,” someone said of her driving across the country alone with four hundred pounds of glass.

“Nah,” Tavonatti replied. “He was packed in there pretty good. He was my co-pilot. I think there was a glow around the truck.” She pressed her lips together in a smile. “You keep yourself in a certain state of grace.”

Tavonatti made a point to spend as much time by her mosaic as she could, meeting people. She let them connect with her. One after another, people asked questions, often the same questions addressed in the artist’s statement posted behind them, and she answered them patiently, as if she had never heard them before. Other ArtPrize artists campaigned for votes, passing out cards on street corners. Tavonatti didn’t do that. She didn’t need to. People came to her. She looked them in the eye, she listened, she responded in a way they understood. She had a calm presence about her, as if she were so focused, so relaxed that she didn’t need to expend any extraneous effort. She wanted to demystify the creative process, she later told me. Make it accessible to everyone. One of her favorite comments came when someone read her statement, which mentioned she was originally from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. “You mean a Yooper made that?”

There were, inevitably, questions about her faith. Tavonatti later told me she did not want to talk about her spiritual life, but much of her language — grace, glow, co-pilot — was language these Christian viewers recognized. “No matter what has transpired during my life,” she wrote in her artist’s statement, “one thing has remained constant, my conversation with the Divine.” This is not Christian language, but no one seemed to notice. Though secularism dominates high art, Tavonatti had made a place for Jesus in an art show. One woman I talked to said, “Being Christian myself, it touches me because other cities have had pieces of art that mock that.” I flipped through my pedestrian knowledge of contemporary art in “cities.” There was Piss Christ. But that was back in 1994. Right? And not connected to any city in any way, except that it was exhibited in one. But asking her for evidence was irrelevant. The point was that art and cities made her uncomfortable. Maybe all art made her uncomfortable. But this mosaic, here, in ArtPrize, stood up for her Christianity. “And I appreciate that,” she said. Even so, the people looking at and admiring Crucifixion wanted to know: Is Mia Tavonatti Christian like they are Christian?

There was a break in the small crowd around Tavonatti. I introduced myself. “We’ll never be able to talk here,” she said, leading me outside to a back terrace along the river. The light was warm on the concrete.

“My mother was just taken to the hospital,” she said. “The doctors put her in an induced coma.” Tavonatti’s mother, who still lived in northern Michigan, had just fallen ill, quite quickly. I asked her if she wanted to talk some other time, but she said no. The doctors said her mother was stable. She wanted to see through the last few days of the final voting. Crucifixion stood a chance at first prize.

We walked to the patio along the river. I wanted to tell her about my interest in dialogue, that I was trying to understand a range of artworks and their appeal. I wanted to come clean, tell her this was not art that spoke to me, but there wasn’t a natural moment to mention this. We found a place to sit. Tavonatti reached up her arm and waved to someone she knew. When her attention returned, I asked about all the questions she was fielding from her audience. She sat with one leg folded in front of her, a kind of half lotus, and exhaled. She seemed almost relieved.

“This piece is not about me, but they want to make it about me. It’s not my ego on the line. They ask questions,” she said. “I can’t even really remember because it’s not my language. Things like ‘Are you a believer?’ I don’t want to have that conversation with just anyone. I want to learn how to be a better channel.”

It was turning out to be an ideal interview. She was relaxed and open, and except for my double agency, I was at ease too. I told her I was writing a piece that may or may not get published, but even in that moment I couldn’t quite articulate what I was writing, aside from trying to understand art I didn’t like, but I couldn’t say that either. It became almost moot. As we talked that first hour, I think we sensed we had more in common with each other than with those milling around the DeVos Convention Center admiring her work. Maybe she wasn’t the strategist I thought she was. Maybe she wasn’t just pandering to the super-Christians. Maybe she was just trying to make her art in the best way she knew how. “This is off the record,” she said to me, “but I’m an energy worker.” She later told me she Reiki’d the hell out of the space where Jesus hung.

So why did Tavonatti’s Jesus have no pain? I wanted to know. He gazed downward without a trace of suffering. This was the heart of my problem with Jesus. My difficulty with Christianity in general. I never understood what it meant for Jesus to die for our sins. The only thing that made sense for me was the fact that suffering connected us. A Jesus without suffering, without some expression of compassion for the pain of human existence, baffles me. If Jesus doesn’t suffer, if Jesus doesn’t show us how to have compassion for our own suffering and the suffering of everyone we would rather not deal with, then what was the point? I spared Tavonatti my inner monologue and just asked the question.

“I wanted a positive Christ, not a bloody, tragic Christ,” she said. The moment portrayed in the mosaic is Jesus before the fifth wound, she explained, before earthly death when a lance is struck into his chest to make sure he is dead. According to the gospel of John, blood and water flowed from the gash. A miracle. “I wanted that moment of complete surrender,” she said. “So when Chris just let his head relax, I said, that’s it!”

Chris, Tavonatti’s model for Jesus, was a former professional surfer. The sun and the clouds in the background of the mosaic were Photoshopped from two different sunsets photographed by Tavonatti. To envelope Jesus in a glow, she devised three different sources of light. She used her massage therapist as a second model to give definition to the muscles and bone that were lost to shadow in the original pictures. And to take some weight off Jesus. “Chris was a little …” She paused, looking for the word. “I wanted him to be leaner.”

I asked her why she thought her work resonated with people. “Beauty is universal,” she said. “It’s as simple as that. I’ve built a whole career on the belief that people can understand beauty.”

Though much of her work is now mosaics made on commission for homes, schools, or churches, for many years Tavonatti worked as an illustrator and a painter. In 2007 she mounted a show of paintings, her Svelata series, in Italy in the Museo Arsenale in Amalfi, paintings she planned to continue to tour in the United States. According to her website, she was working with a Hollywood producer and a Grammy-winning artist to create an experience they will take on the road in a nomadic exhibition. The paintings will not be for sale, but people will pay to see them.

“This is the experience economy,” she explained. “This is what artists are doing in L.A. People want to be social, they want to have an experience, they want to be uplifted.” The exhibition would be housed in a specially designed tensile structure with lighting and music. In the photos I saw, the structures looked like space-age tents, with curved walls and womblike spaces. There would be a cash bar. There would be classy merchandise. People would pay to have the experience, and the artist would be free to create works that move people without the burden of having to sell a painting.

In Where I Was From, Joan Didion writes about Thomas Kincade, the “Painter of Light,” exposing an underside to the fairytale quality in his paintings. “The passion with which buyers approached these Kincade images was hard to define,” Didion writes. “The manager of one California gallery … told me that it was not unusual to sell six or seven at a clip, to buyers who already owned ten or twenty, and that the buyers with whom he dealt brought to the viewing of the images ‘a sizable emotional weight.’ A Kincade painting was typically rendered in slightly surreal pastels. It typically featured a cottage or a house of such insistent coziness as to seem actually sinister, suggestive of a trap designed to attract Hansel and Gretel. Every window was lit, to lurid effect, as if the interior of the structure might be on fire.”

What nasty pleasure it is to see those paintings and their suffocating coziness as an out-of-control blaze from within. Didion doesn’t even attempt to see the paintings as those who love them see them. Perhaps one who hates the paintings, as I do, can only speculate. This is dangerous territory, of course, imagining the emotional and aesthetic charge felt by thousands of faceless owners of official Kincade prints. But if we don’t imagine their appeal, what are we left with? And isn’t there some appeal? Those foggy edges and purpley hues invite escape from this world and its astringent, shadowless shopping-aisle reality into another world entirely.

I had studied the paintings and mosaic in Tavonatti’s Svelata series on her website to try and better understand her artistic oeuvre. In each work she was the model. She painted herself in drapery, lagoons, beds. Sometimes she was alone, but in most paintings she was with a male model. The style was fantasy realism, or hyperrealism. The sheen, the Mediterranean blues, the transparent creamy whites, the perfect Caucasian skin tones were bumped up into a cinematic high definition, achieving a detail that would be lost to the naked eye. The detail was dizzying. In Svelata, the mosaic I panned the year before, the movement was circular — the woman’s arms, the water, the drapery. The glass fragments were also set in swirls to scatter the viewer’s focus, to create, as she put it, a meditative quality to the work.

I met with Tavonatti in two long interviews — once in the final week of voting, and once a week later. At every opportunity, either in person or in email, I kept pressing her, trying to understand what she wanted to convey in her paintings and her mosaics. I was nearly a nuisance, but she showed no sign of irritation. “I want people to get out of their heads and into their hearts,” she said to me more than once. The subjects in her paintings embraced, swam, swirled, touched in various erotic, suggestive positions. The female figure was limp, draped over the male’s arms or alongside his body, but the male figure was stoic, strong. He carried her, held her, spooned her. I felt nausea, not rage. Though these representations had zero appeal to me, I was trying to understand. So, the figure in the paintings wants to be taken care of? OK. I could imagine that in an abstract way. The viewers in Italy who saw her paintings told her they were without words. Words threatened her art. When a critic called Svelata a harlequin cover, Tavonatti dismissed the review. She understood the critics did not like her work, but she saw it as a failing on their part, not hers. The people were the real judges of beauty. They understood. I continued to press her, and she always obliged. I felt like she was giving my skepticism, my inquiry, and thus me, a place to exist. I was charmed, even as the beauty answer was not satisfying me. Not because beauty is relative, but because this was a particular kind of beauty, an overarticulated liquid determinism that left nothing for the viewer to say. If it was beautiful it was beautiful in the narrowest sense. It was a beauty that let in a narrow range of light and color. Narrow thinking. Narrow feeling. The realness it professed was a con.

Still, the more I interviewed Tavonatti, the more I enjoyed her, and the harder it was to come clean. She was such a willing subject. And she enjoyed, I think, being seriously engaged. It became clear she saw this article I was supposedly writing as a celebration of her work, so we both forged ahead. I kept asking my questions. She kept answering them. How was a Catholic image of Jesus on the cross winning such broad appeal in a community of puritanical Christians? Did no one find this ironic? So why are people drawn to her work? I had been pressing her to get past the beauty answer.

Finally, she gave me a new one: “Consciousness.”

Consciousness?

“The critics don’t get it because they are too much in their head,” she said.

Now wait a minute. What could that mean? Were those who loved Crucifixion seeing something transcendental because they had a heightened awareness of the aesthetic and spiritual energies in the world that I lacked? What were they seeing that I didn’t see?

“May I be frank?” I asked. All that billowy loincloth, God’s abs.

“Isn’t it all about the body?” I asked. “The erotic? Isn’t it just about sex?”

“No,” she said. “My work is all about the spiritual.”

Suddenly, I remembered something she had said earlier that evening. I was fixed on the difference between art that is good and art that you like, the Kantian distinction that one does not necessarily follow the other. Why all the perfect bodies? Why the positive Christ, not a tragic, bloody Christ? “Because that is what people can relate to!” she said. “It’s not about whether it’s good! It’s about whether they like it!”

So she was a channel, a superb channel, giving people what they were looking for. I went back to the mosaic. It offered a symbolic place for Christians in the secular temple of “high culture.” And it offered sex at the safety and remove of God. And finally it offered reality and escape all at once. It affirmed that there was something beyond the drab ugliness of the everyday without asking anyone to think too hard about it. No one looking at Crucifixion would feel dumb.

The morning before the final winners were to be announced at the awards ceremony, Tavonatti and I planned to have coffee. It was about a week after our first meeting. Instead I received an email. “My mother died this morning. I don’t think I’ll be doing much talking today.” I felt terrible for her. I had the very unjournalistic impulse to give her a hug. She apologized for not having more time with me, and we postponed.

She still planned to attend the awards, and I planned to observe her. I bought a ticket at the box office — there were plenty available — and arrived early at the DeVos Performance Hall. The cavernous auditorium was darkly lit and empty. I spotted Tavonatti walking alone. Her face was ashen. People trickled in, some in gowns, others in rayon ruffles and skirts. I watched the crowd in the lobby.

The interior décor of the DeVos Performance Hall was a strange collection of relic-like objects from the 1930s and 1940s — an unlit sparkler, a cigar band, a package of Flexitized collar stays. Each object was individually framed, with an inscription, perhaps lines from movie scripts, printed on the glass: “It’s awful, but it’s honest and ambitious, like everything else in this great country,” read one. On another wall were two framed posters from the 1938 film Top Hat starring Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire. I knew this one. I had seen it when I was young and in love with old movies for the escape they offered. As a girl I believed that when I died, if I were to go to heaven, that heaven would be dancing with Fred Astaire in the sunlit fields of my great-grandmother’s farm at dusk. When I watched Top Hat again as an adult, I was surprised at the set — it was white and modern and so obviously fake. To my youthful eye, it disappeared behind all the snappy patent leather and swooshing ostrich feathers. In one scene Fred Astaire slams a door, but it springs back because it is as light as cardboard. The story is vague because the story is not the point. All we need to know is that a beautiful girl, who is not rich, is nevertheless dressed in gowns all day and wooed by an irreverent star who never appears without a tuxedo. This must have hit some sort of chord, after the Depression and before the war. Did anyone notice the door? Probably not. They were looking for something else.

The awards ceremony opened with a violently brassy song and dance number and silvery spotlights lit up the stage. Tavonatti and the other finalists sat in the front row, most of them wearing black jeans.

The finalists had taken a beating in the press. The local paper, which normally celebrates its populist anti-intellectualism, called the top ten pedestrian and disappointing. One reader called them silly. The artworks that were selected for the top ten included sea creatures carved out of driftwood displayed on a motorized lazy Susan, five chainsaw bears set in a public fountain, a giant praying mantis made of steel, a human sculpture routine, a giant dog made out of obsolete car parts, a three-dimensional mosaic mural, an abstract work of several massive pieces of paper cut with a repeated pattern, another abstract work of many silver squares hanging, a super-realistic sculpture of Gerald Ford admiring a bronze bust of Gerald Ford, and Crucifixion.

Local sponsors presented a handful of juried awards to artists whose work deserved recognition but didn’t grab the attention of the popular vote. After halting technical difficulties with lights and video cues, Rick DeVos finally came onstage to announce the awards for the big prizes. Third place, second place, then first. Mia Tavonatti. Crucifixion. She rose from her seat and walked up to the stage holding the stair railings with both hands. As she accepted the medallion, she pressed her hand to her heart. The stage was empty. DeVos and Tavonatti stood slightly apart. The video camera, which projected its image on a screen hanging over the stage, could not quite get them in the same frame.

After the show, the lights in the press room were white and hot. Six TV cameras waited, pointed at an empty table in front of an ArtPrize screen. Young girls in gem-neckline satin dresses and platform heels were handing out press releases. No one asked me for credentials or a press pass. We waited. The room was quiet. People coughed, sniffled, whispered. When Mia finally entered, the applause was tepid. “Did you hear her mother died this morning?” someone whispered. The first question from a local TV reporter: “How does your faith affect your work?

“Faith plays a role in everything I do,” she said.

Mia eventually found me out. Months after the contest, a message pinged into my inbox: “Ahhh … now I remember,” she wrote. She quoted my review from the year before: “And second place has gone to further the important aesthetic advancement of Malibu living room art! Fabulous. The first and second place winners suffer from the same flaw: They are both exceptionally detailed works, both of which required terrific talent and skill to compose. But their subject matters have no apparent aesthetic merit. Both works draw our attention to the creation of the thing, not to the thing itself. How many times have you heard how many hours it took to make these? It’s not irrelevant, but it certainly isn’t the point.”

“It’s very dangerous,” she warned me, “to talk about things you know nothing about.” I took some exception to that last point, but it didn’t matter. The conversation was over.

Mia had come back to Grand Rapids after her mother’s funeral, before finally returning to California. During our last meeting, we met for dinner, had a long interview, and then she spoke to a class of drawing students at the local community college. Much was behind her. She had won the people’s vote. She had posed for photo shoots and sat for interviews. And she had buried her mother. She strode into the classroom as students crouched behind their easels.

“I’m Mia Tavonatti,” she said, “and I won ArtPrize.”

Mara Naselli is an editor and writer. Her essays have appeared or are forthcoming in Fourth Genre, The Kenyon Review, Agni, Ninth Letter, The Hudson Review, and elsewhere. She writes about literature for 3 Quarks Daily (www.3quarksdaily.com).