Letter from Singapore

By Ho Lin

In Asia, most cities jolt to life at night, and Singapore is no exception. For one thing, it’s usually too damn hot to do anything during the day, except hit one of the public pools (until the inevitable afternoon thunderstorm hits). But at night, the clouds hang low, the breeze is pleasant, rooftop bars sparkle, and each lighted hawker centre is its own galaxy of activity.

Yet here in Tiong Bahru, the alleged hipster district of Singapore, the order of the night is a cupcake and a cat, cupcake courtesy of the Plain Vanilla café, cat courtesy of the BooksActually store. At the café, one relaxes with lemon water and a helping of architectural magazines; at the bookstore next door, one happily loses oneself in old issues of Granta, a dog-portrait book sitting alongside a Cahiers du Cinéma issue on Marlon Brando, and of course that cat sitting at the cash register, a gauntlet to be passed and petted.

Apart from the elongated shophouses (“Streamline Moderne” style, Singapore’s National Heritage Board proclaims) and a few bars and pizza joints, nothing in this hood suggests the bohemian buzz one associates with the literary center of a megalopolis. Which is just as well. For all the self-congratulatory readings and events, writing and reading has always been a fundamentally solitary occupation, and few city-states are as inward-looking as Singapore.

Take its location: supersonic skyscrapers and modernity smack dab in the middle of a jungle. Singapore prides itself as a city of gardens, but the landscape goes far beyond that. No matter how many miles of concrete are laid down, you are overwhelmed by the environment: the buzzing insects, the leafy trees, that hot, humid air. Other cities like Hong Kong have all but eradicated nature, but in Singapore, it is forever poised at your doorstep, ready to overrun you in the lushest ways imaginable, if you’re not vigilant.

Then there’s the history: the tug-of-wars between the British, the Japanese, the Malaysians, the well-documented government “oversight” (we won’t get into chewing gum or unflushed toilets), the sometimes uneasy race relations (such as last year’s riot in Little India). Only beginning to dig itself out from under colonialism and commerce, the literary scene here is incipient, fragile, and charming. It’s been said that art is worthless but priceless. Singapore has been getting by with boutique publishers like Math Paper Press, BooksActually’s imprint. A reading at the store feels less like a meeting of glitterati than an initial stirring of ideas and movements. History hasn’t allowed the city a golden era of literature, but it might not be too late to join the party. It seems entirely appropriate to be munching on a cupcake while doing so.

•

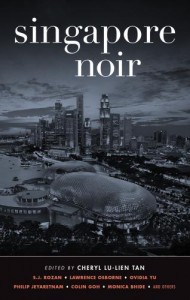

Speaking of joining the party, Singapore was recently welcomed to Akashic’s world-spanning noir anthology series (everything from Baltimore to Zagreb). John Le Carré once wrote that the secret service is the truest expression of a nation. One could say the same for crime stories, and Singapore Noir offers at least a glance at the city’s character. What it actually says about that character is a bit muddled, as you would expect from a town of conglomerated cultures and geographies. If most of the works in Singapore Noir lack the fatalism of noir, they at least give their authors license to go on a lark and touch on what it means to live in this literal urban jungle.

Some of the stories, like Colin Goh’s “Last Time,” about a grubby Chinese Communist cadre and a pop-idol femme fatale, are emblematic of cosmopolitan, transnational Asia as a whole. Others like Ovidia Yu’s “Spells,” in which gentrification (in the form of an uppity new neighbor) gets its ass kicked thanks to some ancient spells, lean on local superstitions. Throughout, we get a plethora of types: Japanese and American expats, wizened locals, fishermen and businessmen, mediums and maids.

Some of the stories, like Colin Goh’s “Last Time,” about a grubby Chinese Communist cadre and a pop-idol femme fatale, are emblematic of cosmopolitan, transnational Asia as a whole. Others like Ovidia Yu’s “Spells,” in which gentrification (in the form of an uppity new neighbor) gets its ass kicked thanks to some ancient spells, lean on local superstitions. Throughout, we get a plethora of types: Japanese and American expats, wizened locals, fishermen and businessmen, mediums and maids.

The better stories in the collection reshape the usual motifs for witty ends. Simon Tay’s “Detective in a City with No Crime” sets up an adulterous affair between a gumshoe and a mob man’s wife only to finish with an unanswerable existential puzzle. “There is sin in Singapore, in the very word of it,” the nameless detective muses, yet sin itself disappears like morning mist, leaving only guilt.

On the lighter side, Nury Vittachi’s “Murder on Orchard Road” chronicles a madcap day in the life of C.F. Wong, feng shui master, geomancer, and event organizer, who has to track down the kidnapped son of a local scion while also solving a murder and brokering a truce between a Buddhist monk and two Formula One drivers. Although all is resolved to everyone’s satisfaction, Wong’s ruminations on crime wouldn’t sound too out of place in a Raymond Chandler novel, “Murders were horrible, messy, smelly, difficult heart-rending things. And not nearly as profitable as they used to be.”

One can detect classic noir antecedents in other stories. Colin Cheong’s “Smile, Singapore” is a version of Taxi Driver in which our protagonist doesn’t get the easy way out. Monica Bhide’s “Mother” recalls the horrors of Hitchcock’s mothers in Psycho and Marnie, with a comeuppance to match. Damon Chua’s piquant “Saiful and the Pink Edward VII,” in which a punk rocker has to go to extremes to recover a valuable stamp that’s also a family heirloom, plays like Pulp Fiction out on a bender with Boogie Nights.

•

Singapore Noir is a playful sugar rush of a cupcake. One senses that the authors are content to have fun without getting too heavily into the heart of what makes their town tick. In contrast, Math Paper Press’s Balik Kampung 2B is both more ghostly and more substantial. The second in an anthology series written by authors who grew up in specific Singapore neighborhoods, it aims to document the city’s boroughs. As you’d expect from something intended as a testament and elegy, it shades towards melancholy.

A phantasmagorical mix of fiction, memory, and meditation, Balik Kampung 2B’s tales are all about the changing faces of Singapore. Ann Ang’s “Gedong Gold,” in which a narcoleptic, unemployed ne’er-do-well gets lost in the boundaries between jungle and city, and past and present, all in the pursuit of a few durians to sell, exemplifies this approach. Other pieces are straight autobiography, such as Cyril Wong’s devastating “The Vomiting Incident,” which picks apart the collapse of the author’s family in a tenement building, along with the erosion of youthful certainties about love.

Serious stuff happens—as in Tania de Rozario’s “Certainty,” in which a mother kills her infant son, the stresses of high-rise living giving way to a final fall—but the authors have clear affection for the neighborhoods about which they write, whether or not they still exist. Zizi Azah’s “Such Great Heights” recalls Rick Moody as its female protagonist recounts glorious days of summer ennui with her philosophically inclined buddies, luxuriating at a time of life in which break-ups and long drives deep into the night seem to mean everything. On the other end of the generational spectrum, we have the elderly couple in Wei Fen Lee’s “Cure Us of Prayers.” Seeking out a local temple for prayers, they instead stumble on the detritus of their neighborhood’s past and a measured acceptance about the dying of the light. Desmond Kon Zincheng-Mengde’s “Flying in the Face of Denouement,” a relentlessly intellectual rumination on the end of a relationship that muses on everything from Freud to Johnny Depp, neatly sums up the entire project:

It was the strangest marriage of different things. People, customs, language, food, dress, how people looked at each other, and then stopped themselves in mid-thought and looked at the ground, as if suddenly they were forced to look at themselves, with an anthropologist’s remove and objectivity.

Defiant in its allegiance to the city and the act of being literary, Balik Kampung 2B is not as polished an affair as Singapore Noir, but as a collection it cuts deeper.

•

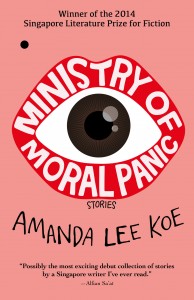

So we’ve gotten a look at the here and now as well as the past. What about the way forward? Clues can be found in Amanda Lee Koe’s short-story collection Ministry of Moral Panic, winner of the 2014 Singapore Literature Prize. Lee is among the latest generation of Singapore writers, and as you’d expect, you can catch the whiff of Haruki Murakami and Wong Kar-Wai in her stew of influences. Like those auteurs, her characters are adrift and borderless, finding joys in the most tenuous of connections.

“Every Park on This Island” hopscotches like Cortázar, the personal history of the narrator and her American beau bound up in the geography of a Singapore that’s a blank slate, ready to twist in any direction. “Cities are cities,” pooh-poohs the would-be boyfriend. The image of a modern Singaporean gal dressed up in ’20s flapper finery is just as valid as the taste of the sea on the characters’ tongues or the trees waving over their heads. “The King of Caldecott Hill,” meanwhile, is a spiritual sequel to Chungking Express, as a suicidal television star crosses paths with a young waitress who happens to be his biggest fan, and a chaste night spent in a hotel room ripples out into a lifetime of obligations.

“Every Park on This Island” hopscotches like Cortázar, the personal history of the narrator and her American beau bound up in the geography of a Singapore that’s a blank slate, ready to twist in any direction. “Cities are cities,” pooh-poohs the would-be boyfriend. The image of a modern Singaporean gal dressed up in ’20s flapper finery is just as valid as the taste of the sea on the characters’ tongues or the trees waving over their heads. “The King of Caldecott Hill,” meanwhile, is a spiritual sequel to Chungking Express, as a suicidal television star crosses paths with a young waitress who happens to be his biggest fan, and a chaste night spent in a hotel room ripples out into a lifetime of obligations.

Lest you think that all this might get a bit too precious, Lee also shows she doesn’t forget where Singapore has been with “Flamingo Valley,” with its nostalgic flashbacks to 60s rock and the birth of a new nation. “Fourteen Entries from the Diary of Maria Hertogh,” based on a true story, delineates the shifting borders between East and West through the inner life of a Dutch girl raised by a Muslim family who is taken back by her birth parents to an unfulfilled life in the Netherlands. Lee also knows how to get down-and-dirty with urban fairy tales in “Two Ways to Do This,” which starts and ends with a Javanese witch who predicts a cruel fate for a village girl, and Lee doesn’t hold back on the ugly details of the girl’s indentured servitude and sexual abuse.

Still, Lee is most effective in stories where Singapore becomes a free-form fantasy playground of possibilities, as her characters hang out at designer cafés, laundromats that double as karaoke halls, and high-falutin’ art galleries. Even sexual boundaries are a free-for-all, whether it’s the transgender fish-man in “Merlion” or the star-crossed lesbian lovers of “The Ballad of Arlene & Nelly.” “Being used to something is such a poor excuse for prolonging anything,” one of her characters sighs. Her stories are resolute in their refusal to tie themselves down for long.

Amid these doomed lovers and self-conscious narrators, one senses an innocence in Lee’s work waiting to mature into something that has a bit more weight and consequence. “Loneliness is freedom,” concludes the divorced wife at the end of “Love Is No Big Truth.” Singapore may be stretching its muscles in its first throes of literary freedom, but loneliness seems like only a detour on this road. Fittingly enough, Ministry of Moral Panic, just like the city of gardens, is an exciting collection of beginnings, with uncertain endings far ahead.

Singapore Noir

Edited by Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

Akashic Books (June 2014)

ISBN 9781617752353

Balik Kampung 2B

Edited by Verena Tay

Math Paper Press (2013)

ISBN 9789810776541

Ministry of Moral Panic

By Amanda Lee Koe

Epigram Books (October 2013)

ISBN 9789810757328

About the Author

Ho Lin is a writer, filmmaker, and musician (in other words: jack of all trades, master of none) who lives in San Francisco. He is co-editor of the literary journal Caveat Lector, and more of his work can be found at www.holin.us and www.camera-roll.com. He can be pinned down on Facebook.

Ho Lin is a writer, filmmaker, and musician (in other words: jack of all trades, master of none) who lives in San Francisco. He is co-editor of the literary journal Caveat Lector, and more of his work can be found at www.holin.us and www.camera-roll.com. He can be pinned down on Facebook.