An Interview with

Karen Tei Yamashita

By Karen An-hwei Lee

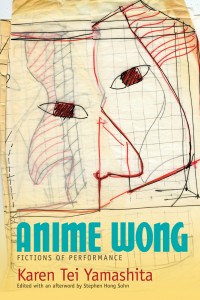

An avid fan of Karen Tei Yamashita’s fiction—Brazil-Maru, Through the Arc of the Rainforest, Tropic of Orange, Circle K Cycles, and I Hotel—I was thrilled to pick up Anime Wong: Fictions of Performance, the long-awaited anthology of electrifying performance worksedited by Stephen Hong Sohn in collaboration with Yamashita herself. Readers of Yamashita’s award-winning novels will be delighted to see her irreverent cultural motifs come alive through playscripts and archival photographs of the past three decades.

Noh-meets-circus-act, avant-garde chicken opera-in-a-tale, musical comedy, karaoke, a short film, commercial interludes, and CyberAsian manga enact fantastical collisions of techno-Orientalism, multiracial triangulations, an invasion of Little Tokyo by GiLArex, and a Japanese American female body politic in the future. Orbiting the global microcosm of greater Los Angeles, this eclectic volume gathers Yamashita’s performance fictions of hybridized sub-genres, including those written during her early forays into theater of the late Eighties.

How did your first experiences with writing for theater and film inform your technique as a novelist?

I believe I learned in this process to listen to or to hear the voices of my characters, that narrative voice is a construction that is open to interpretation but requires a cadence and syntax. Hearing actors recite what I wrote made me think about what I heard and what they were hearing.

Would you please describe the process by which you collaborated with Stephen Sohn to assemble this volume? Are any performance fictions not included, and if so, why?

I handed over a box or boxes of my theater work to Stephen, and he pulled out everything, separated the actual scripts from playbills, photographs, set designs, reviews, and other saved material, and handed me a large notebook, a collection of scripted plays and performances. I was surprised because he found material about which I had long forgotten. I know he wanted to publish everything, but I always think about what makes a book, and we had to dicker about this. From early on we could see a pattern of interest regarding the U.S. relationship to Japan as an economic threat and ideas about the future of Asian Americans. When I had a better sense of this, I wrote three more performances to bring these issues up to date. As for what got left out, well, I removed an early identity play and several plays set in Brazil, in the Japanese Brazilian community. We also left out an unfinished musical written with Vicki Abe about an all girls rock band. In the meantime, Stephen had the short film I wrote with Karen Mayeda transcribed and wanted to include a short story connected to the performance of Hannah Kusoh: An American Butoh.

The way you describe the live energy of performance—and your gratitude for community—is marvelous: “A flat text on the page stood up and became voluminous, a wild beast, never entirely tamable, and this was exhilarating and dangerous. So many creative people devoted their time and risked their passions to be there …” As you reflect over the decades, what aspects of community performances do you recall with special fondness or appreciation?

As a fiction writer, I live in a room with my thoughts placed on paper. With a book, eventually, you emerge and share the work and see what your readers think. With theater, you get to see and hear live embodied interpretations. The collaboration is what is special. Something I wrote down became an actual dance on stage. Words were given song and sound. I remember sitting next to Vicki when she played each of my songs on the piano for the first time. I felt speechless with emotion every time. Of course, sometimes an actor would say the lines I’d written, and I’d cringe with the revelation that it wasn’t working, and that was also important. I had to go back to the script and rewrite. That my collaborators were willing to recreate my text from page to the live stage, that was a trust I have to respect and honor.

Your visual allegories of cultural production are frequently cast in satirical contexts, i.e., cellophane for a literal glass ceiling in Noh Bozos: A Circus Performance in Ten Amazing Acts, a figurative strategy also present in your novels. What fuels your imaginative creative process? Initially, are you inspired by hybridized forms or structures (i.e. Noh + circus act), situational contexts, characterizations, or all of the above, synchronously?

Your visual allegories of cultural production are frequently cast in satirical contexts, i.e., cellophane for a literal glass ceiling in Noh Bozos: A Circus Performance in Ten Amazing Acts, a figurative strategy also present in your novels. What fuels your imaginative creative process? Initially, are you inspired by hybridized forms or structures (i.e. Noh + circus act), situational contexts, characterizations, or all of the above, synchronously?

I’m really not sure. That is, I’m not sure what came first, the metaphor or the structure. For example, Hannah Kusoh:hanakuso means, well, boogers, the detritus that emerges from your nose. As sansei kids growing up, and probably poking around our noses, we all learned this word. Originally we had this idea about a dance performance in which dancers in bags tumbled out of a large American nose. I remember sitting in the theater and telling Mako this. He said, you need to write it down. I responded, it’s a dance, you can just choreograph it. He insisted on the written work. At some point, I structured it around the five senses plus a sense of intuition, and filled in all the parts as acts. I guess it turned out to be about a woman’s body. The same was true about Noh Bozos. And as you note what also fuels the writing is always a rather mean sense of satire, which I am helpless to abate.

Kusei: Endangered Species—A Short Film portrays a frozen ice-cream-queen and ninth-generation Japanese American woman crowned “Miss Gardena” who’s resuscitated in the year 2244. The film script is replete with allusions to “Ford-Mitsubishi Wars” and the relocation of the Japanese American Citizen’s League “to planet Topanzanar.” How do you envision greater Los Angeles a thousand years from now?

To clarify, Miss Gardena is a sansei queen frozen in time who is paired with a ninth-generation (kusei) who is the last Japanese American of his male kind. If Miss Gardena has been preserved by accidental cryogenics, Kusei has been preserved by cloning.

As for a future L.A. a thousand years from now, I have no idea. We don’t seem to be doing such a great job of preserving the planet.

For your work as a writer and professor in an academic setting, is the history of literary reception on your radar? If so, how would you describe the initial reception of your performance fictions in comparison to their reception today? How do your performance fictions exist in reference (or not) to Asian American theater in general, which tends to be traditionally representational?

When we originally produced these performance in the 1990s, I had the feeling that they were not entirely understood, that they seemed abstract or strange or offensive to our audiences. Now they seem rather obvious and kitsch. Not that others weren’t also doing this, but I guess I was trying to bring something else or some other kinds of presentational modes to this theater to critique what I saw contemporary to our political and social climate: yellow peril fueled by Asian economic prowess and orientalist representations of Asian bodies. It’s been a while, but in fact in this respect, not a lot has changed.

What are you reading right now?

I am reading student writing and preparing for my classes. When I teach, I don’t write or read much else, unless it is related to teaching. Let’s see. Meena Alexander will visit UCSC next week, so I will be rereading her work, The Poetics of Dislocation, and her book of poetry, Birthplace with Buried Stones. Otherwise, I have many many books waiting on the tarmac.

Anime Wong: Fictions of Performance

By Karen Tei Yamashita

Edited with afterword by Stephen Hong Sohn

Coffee House Press (February 2014)

ISBN: 978-1566893404

About Karen Tei Yamashita

Photo of Karen Tei Yamashita by Carolyn Lagattuta. Courtesy Coffee House Press

Karen Tei Yamashita is the author of Through the Arc of the Rain Forest, Brazil-Maru, Tropic of Orange, Circle K Cycles, and I Hotel, all published by Coffee House Press. I Hotel was selected as a finalist for the National Book Award and awarded the California Book Award, the American Book Award, the Asian/Pacific American Librarians Association Award, and the Association for Asian American Studies Book Award. She has been a US Artists Ford Foundation Fellow and is currently Professor of Literature and Creative Writing and the co-holder of the University of California Presidential Chair for Feminist & Critical Race & Ethnic Studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Yamashita is the recipient of an American Book Award and the Janet Heidinger Kafka Award. A California native who has also lived in Brazil and Japan, she teaches at the University of California-Santa Cruz, where she received the Chancellor’s Award for Diversity in 2009.

About the Interviewer

Karen An-hwei Lee’s  most recent poetry collection is Phyla of Joy (Tupelo 2012). Her volume of criticism, Anglophone Literatures in the Asian Diaspora, appears in the Cambria Sinophone World Series. An NEA Fellow, she holds an M.F.A. from Brown University and a Ph.D. in literature from the University of California, Berkeley. She serves as Professor of English and Chair at a small liberal arts college in greater Los Angeles. Lee is a member of the National Book Critics Circle.

most recent poetry collection is Phyla of Joy (Tupelo 2012). Her volume of criticism, Anglophone Literatures in the Asian Diaspora, appears in the Cambria Sinophone World Series. An NEA Fellow, she holds an M.F.A. from Brown University and a Ph.D. in literature from the University of California, Berkeley. She serves as Professor of English and Chair at a small liberal arts college in greater Los Angeles. Lee is a member of the National Book Critics Circle.