Leanne Grabel

chapter 28: the first day of the rest of my life

You can spend minutes, hours, days, weeks, or even months over-analyzing a situation …justifying what could’ve happened, would’ve happened … or you can just leave the pieces on the floor and move the fuck on.

– Tupac Shakur

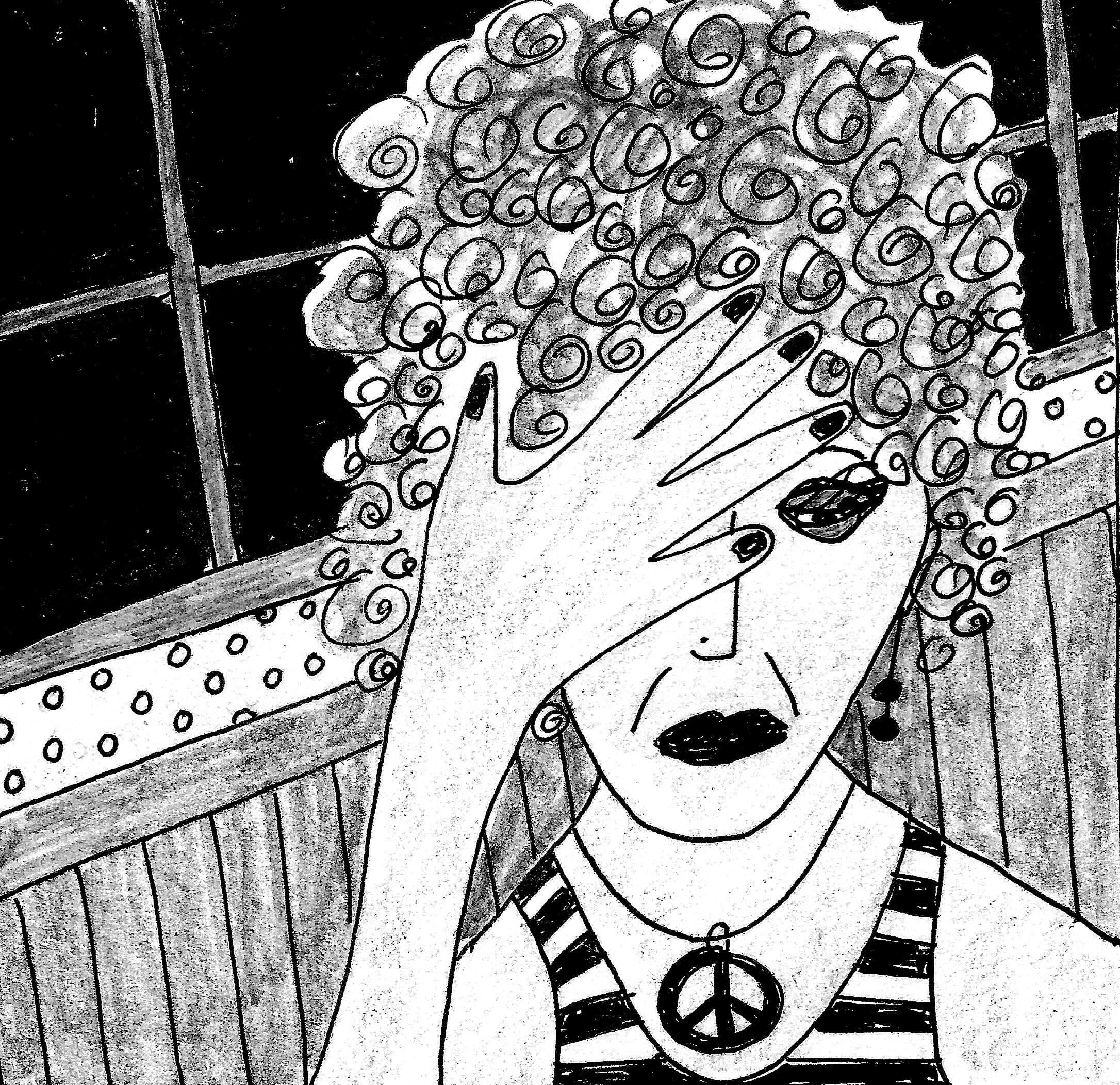

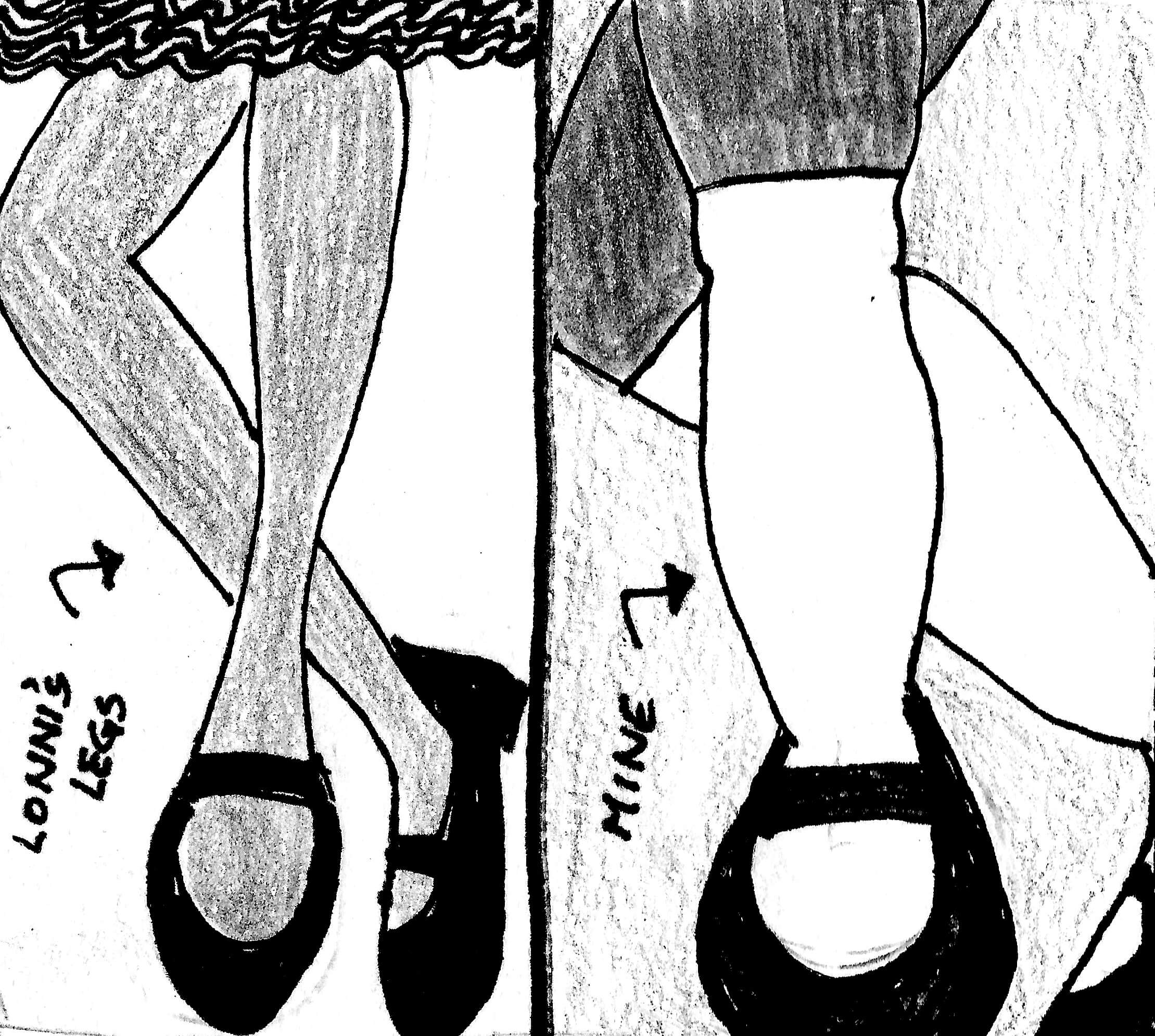

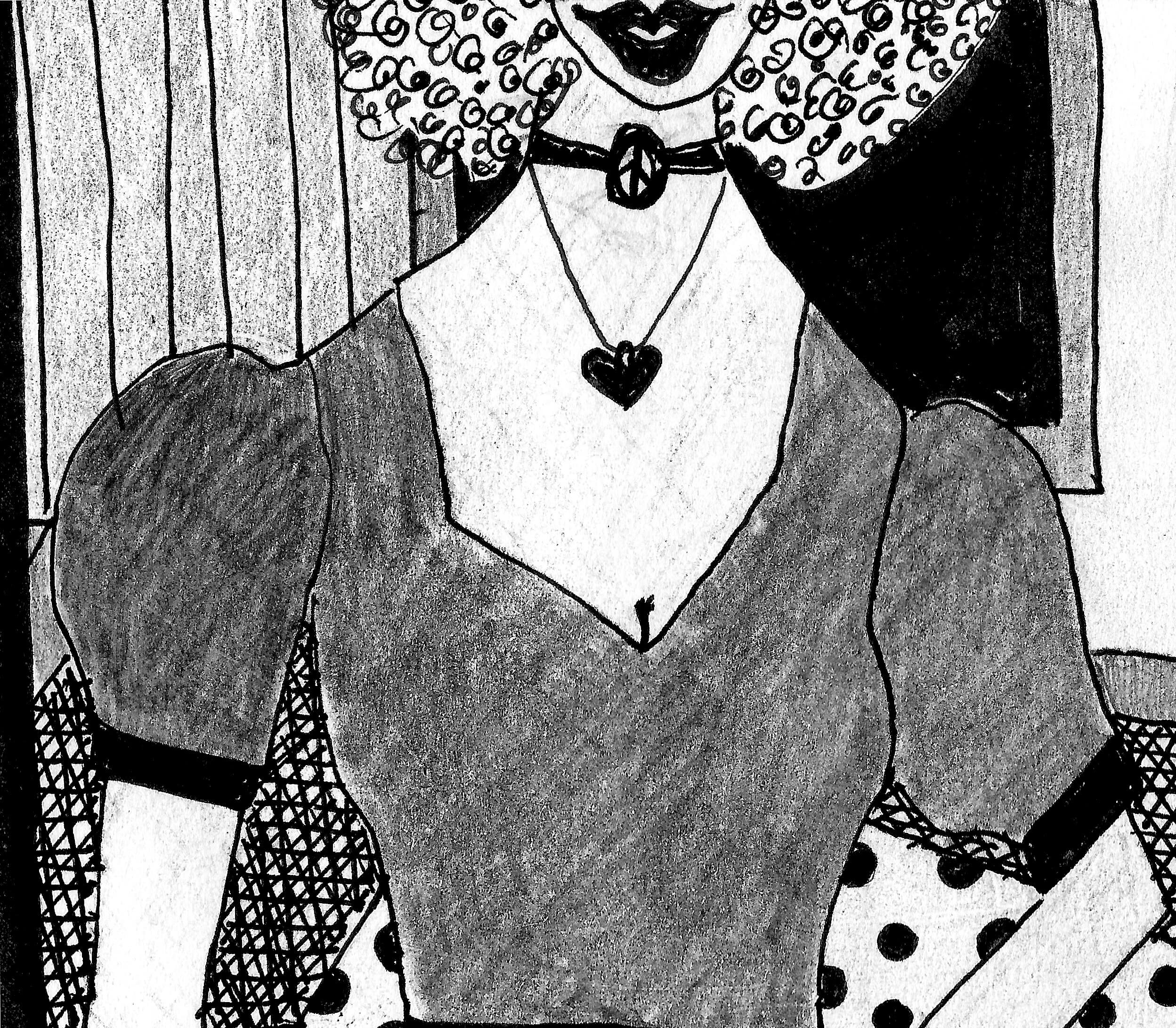

I ran into Lonni Britton in the Lucky’s parking lot a couple days after I got back to Stockton. Lonni was my best friend in seventh grade. She was also my idol. My parents forbade our seeing each other midway through eighth grade. They thought she had too much power over me. And they were right. She did. I was gaga over Lonni’s imagination and her warped sense of absurdity. She had the best brain and best ideas. And she had the best art supplies. She had the best jokes. I laughed all the time. Lonni also had the best legs and the best shoes. I always bought the same shoes Lonni bought. But they never looked anything on me like they looked on her. They looked like paddles on me. On Lonni they looked like magic slippers.

So one day in seventh grade, Lonni and I went to Macy’s and we filled out applications for a teen beauty contest in the names of all the fat girls. It was Lonni’s idea. But I was thrilled to go along with it—to do a little soft-shoe with the Devil. I was laughing so hard, I was slobbering.

The contest applications were stacked in a clever cardboard display with a cutout head of a beautiful teenage model with a perfect flip and perfect skin and a perfect nose. I was slobbering all over the glass countertop. And Lonni was as cool as a queen with her eyebrows in the air wearing their crooked smiles.

In any case, it was ten years later and Lonni was inviting me to a party at her grandmother’s house that weekend. In the gold country. The foothills of north-central California.

“Sure.” I said. “Why not?”

I was free. I felt pretty. I felt thin. I had jeans I liked. And a black t-shirt with a well-designed neckline with minimal plunge that revealed minimal cleavage—nothing gaudy. Just enough.

I made a choker the night before from a tooled gold peace symbol and a black satin ribbon.

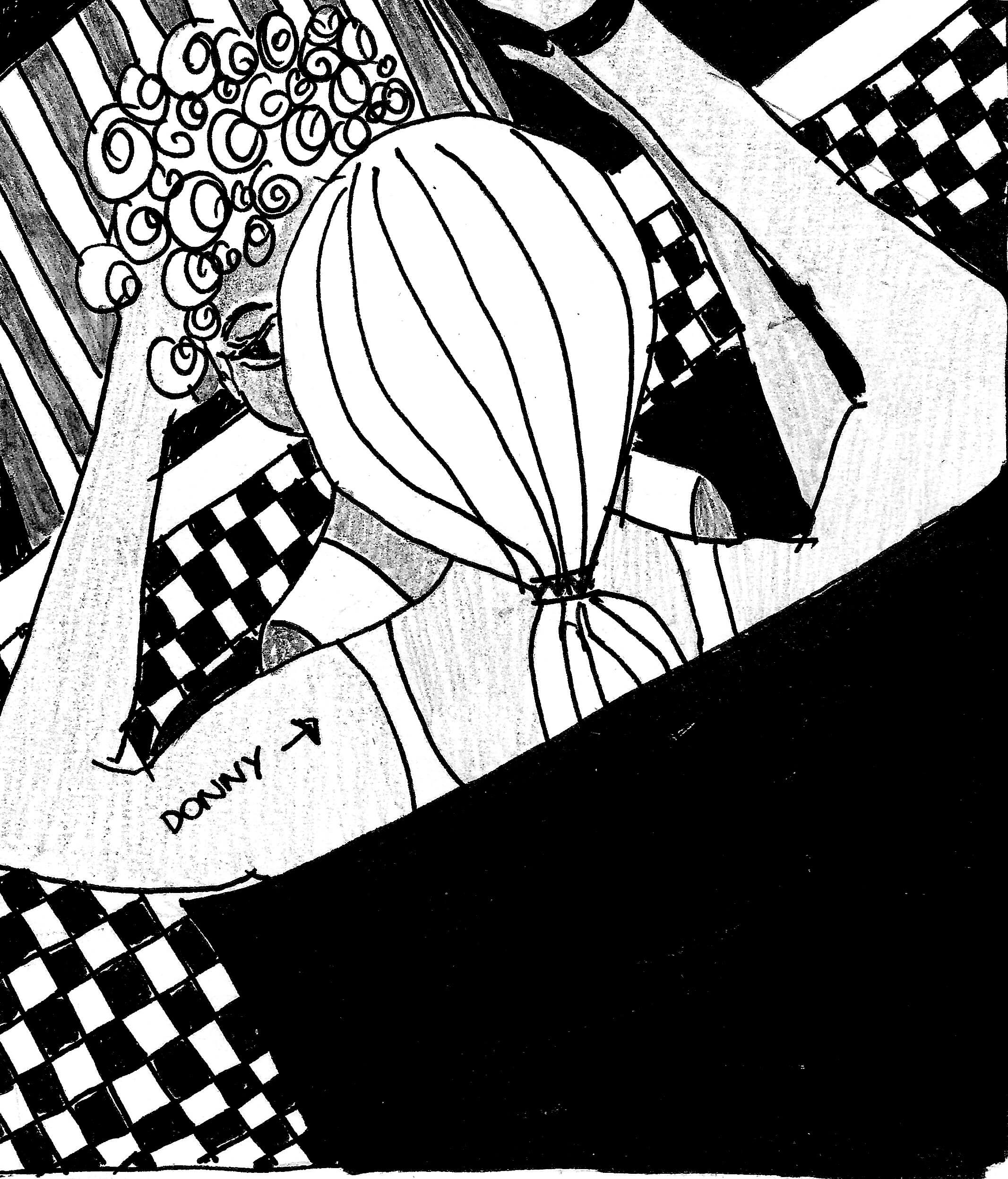

Donny started coming on to me right away. He had a sweet face and clear blue eyes. He had natural white-blond hair that was long and pulled back into a natural white-blond ponytail. My god. It bolted halfway down his back like lightning. I found it phenomenal. Donny’s hair was the exact opposite of mine—a large cap of black frizzle. I was in.

Donny and I whispered to each other in a corner for hours. Everyone else went to sleep, then Donny and I started making out on top of his sleeping bag amidst a lagoon of sleeping people. We kissed and caressed. But I couldn’t relax. I was afraid someone would wake up and see us. That would be embarrassing. I kept an earnest slice of eye peeled at all times. The next morning, I looked like a dog that had just thrown up under the table.

I drove back to Stockton with Donny. Donny wanted to pick up some of his things in his parents’ garage. I didn’t tell my parents I was in town. I’d never been in Stockton without their knowing before. It felt mean.

The next night Donny and I made love in his friend’s parents’ guestroom—about twenty blocks from my parents’ house. I’d never had sex in Stockton before.

It was hard to relax.

I was worried Donny was just too slow-paced for me. I mean, if I were Hong Kong, Donny was Sequim, Washington. If I were Los Angeles, Donny was stasis. But ignoring my instincts, as usual, I asked Donny if he wanted to move to Portland with me.

“It has a river running through it. Like Paris. And it has bridges. And stairways. I have a good friend from college living there. My best friend. Thea. And her boyfriend is from there.”

“I’ll go where you go.”

If I were a beehive he’d be …

… a stone.

chapter 29: portland

And the hooded clouds,

like friars,

Tell their beads

in drops of rain.

– Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

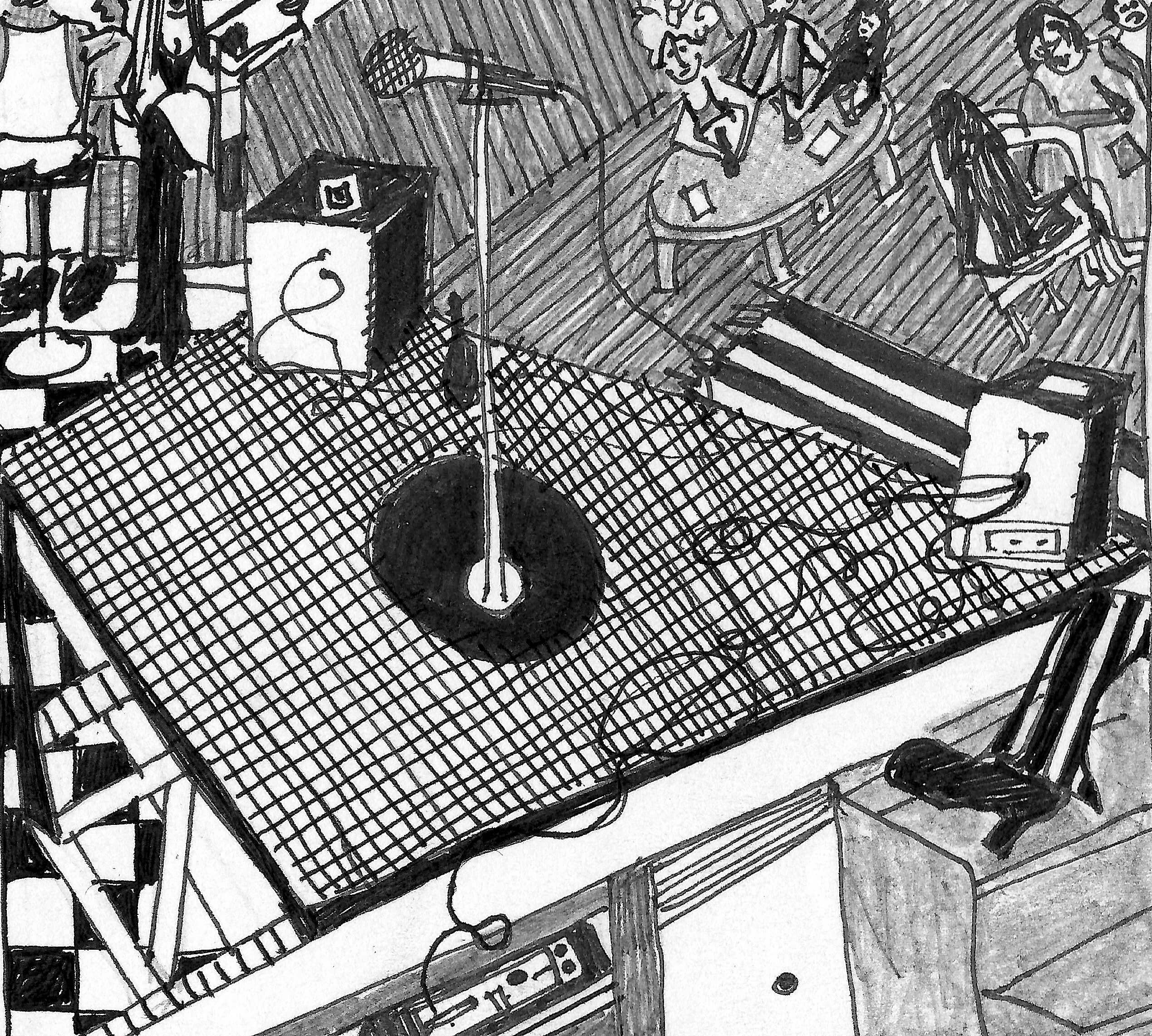

I came up to Portland to visit Thea for a few days before I decided where to move. She took me to a poetry open-mike. I’d never been to a poetry reading or a poetry open-mike in my life. I did, however, write poetry, and read poetry—mostly the tragics, Sexton and Plath, etc.

It was a magnificent night of my life. I fell in love at first sight with every single poet there.

I fell in love with their lack of convention, lack of pretension, scads of invention. And silver teardrops. I fell in love with their marvelous sense of the absurd. And their lyrical celebration of life askew. I fell in love with their histrionic rejection of Wrong.I fell in love with their hair. It was silly. Their hair and their brains were akimbo, ears barbed.I fell in love with the way they played their mouths and hands like hybrid percussive wind instruments.

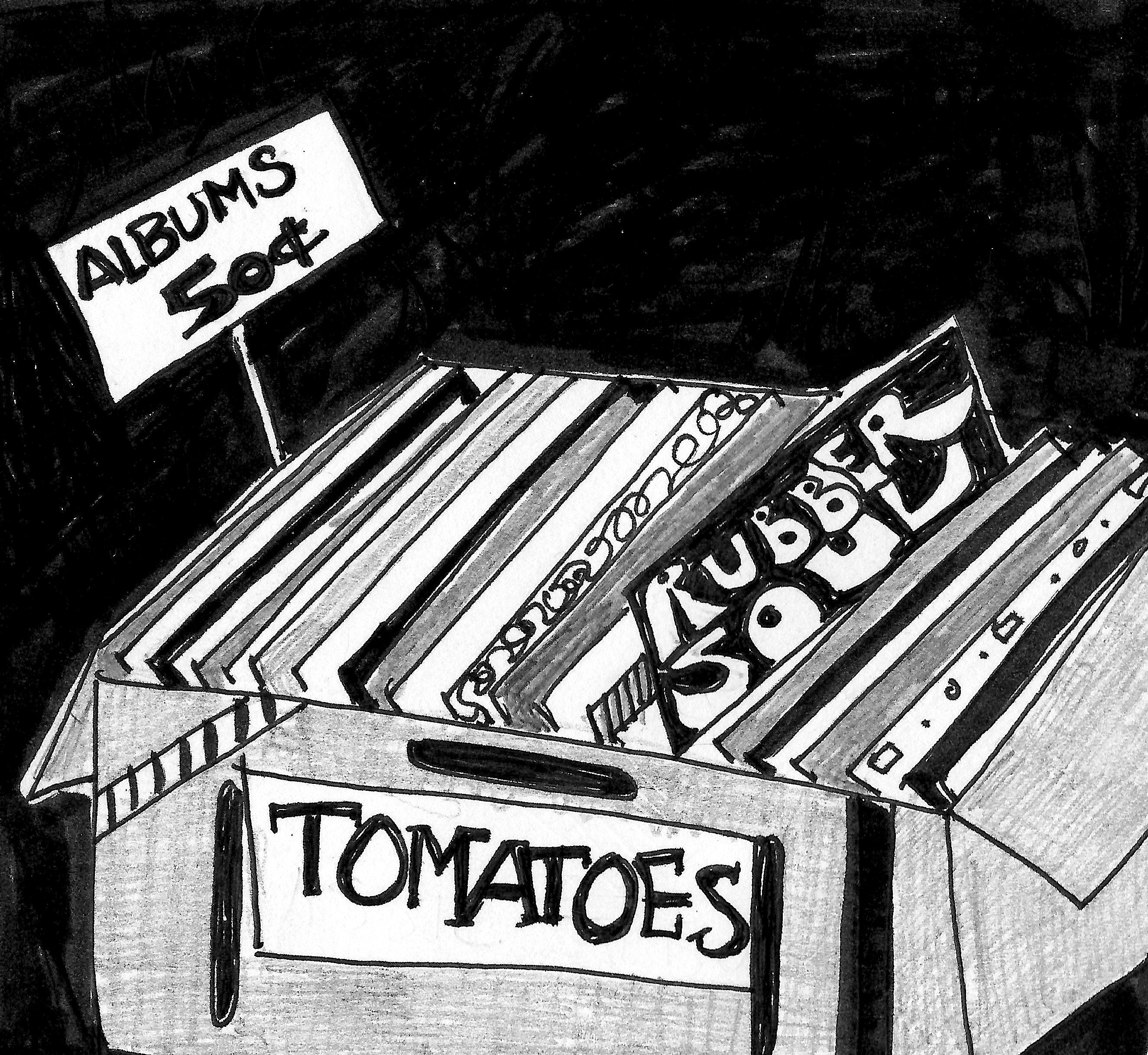

Portland was it. I was moving to Portland, and Donny was coming with me. It was 1975. I sold almost everything I owned. I sold my stereo and most of my best albums like Meet the Beatles and Surrealistic Pillow and Highway 61 Revisited. I held onto my typewriter, most of my shoes and scarves, one coat, two pairs of jeans, my pillow, my journals, and my best pens. We were traveling in Donny’s old ’61 Ford wagon. It was a mommy’s car, once gleaming white and chrome. Now the car was scabby with rust as if riddled with an ugly skin rash. It was a pied cow.

We were on the road in two weeks. We took the coast road and drove forever. But the instant we entered Oregon the sky grew vast and magnificent. The clouds grew busy and ripe with moisture. Quiet hills in woolen slippers tiptoed over fat avuncular hillsides. The mountains were the size of continents. All wore trees like jewels. There were so many trees.

Mt. Hood was geometrically balanced and dominated the sky. She looked dependable and protective, with her broad shoulders and dramatic white cap. Oregon was already relaxing. I felt like I was getting out of a sauna, after staying in too long, and lying down on a cool green lap of lawn.

Donny and I had one address in Portland. It was the house of a childhood friend of Thea’s boyfriend Frank. He told Frank we could stay in his finished garage for a couple weeks until we figured things out. He said it had a sink, a rug, and a pull-out couch.

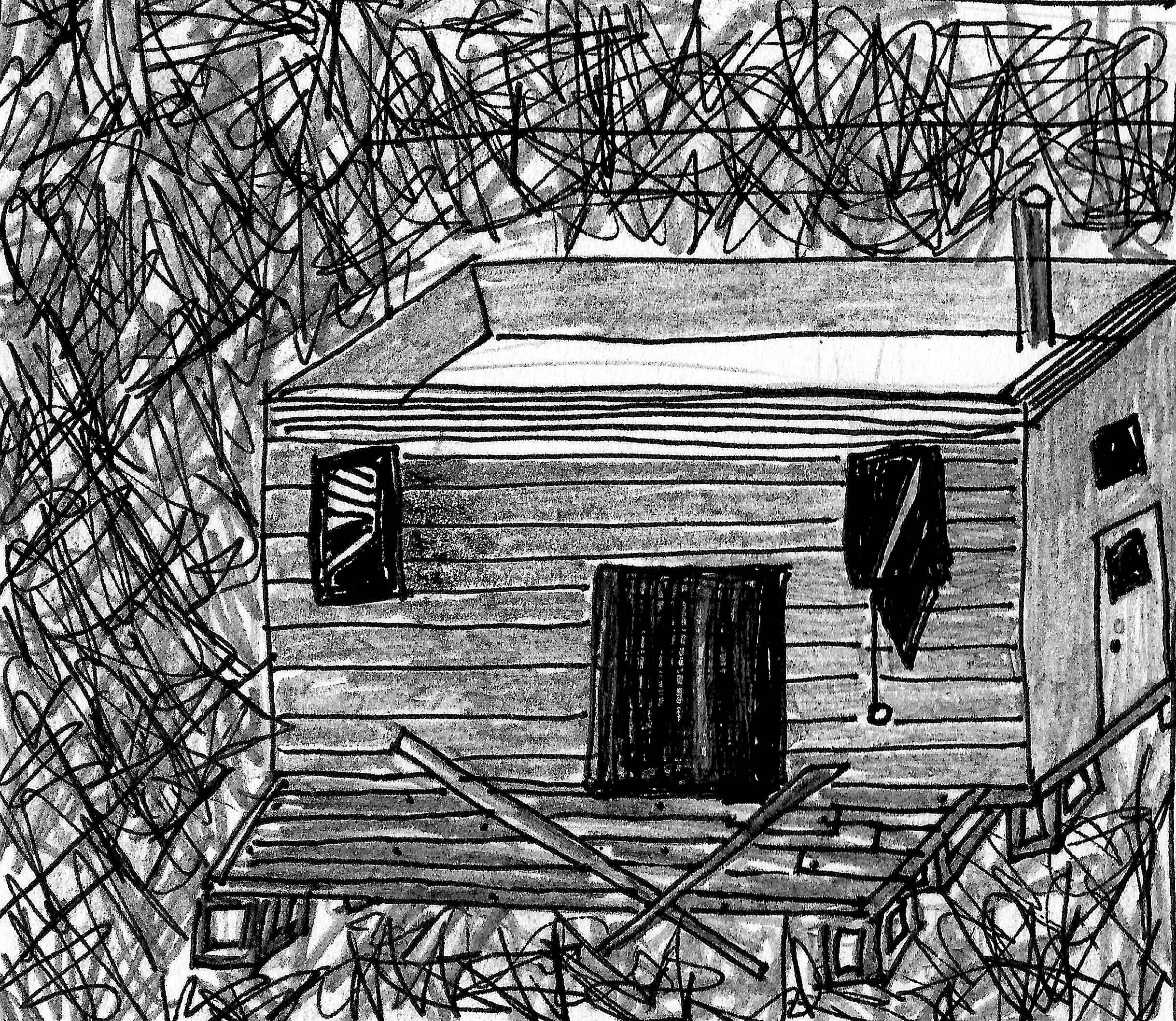

We drove up to the ugliest house I’d ever seen in my life. It stood gracelessly in the middle of a mud-caked lot. The house was the color of envy. No. It was the color of the stains of envy. It wasn’t gray, or green, or brown. It was a faux-wood cube. There was a tinier cube attached in the back. It had no porch other than four boards on cement blocks. There was not a sprout or sprig of green. Dead shrubs, sticks, and stems were strewn about like an old man’s hair.

The pullout couch was torn, lumpy, covered in cat hair, and stinky with piss. The sound of traffic never stopped. At five the next morning, I screamed at Donny.

“Wake up! Let’s go.”

We went to a Denny’s. We both ordered a Grand Slam breakfast: Two pancakes, two eggs, two bacon strips, two sausage links, coffee, and toast. My god. I felt like I had wool socks on my eyes. At seven we called Frank. He said we could camp in his cousin’s backyard for a week. Not.

We saw a For Rent sign on a big raggedy-looking wood house on our way over. We called. A man told us to meet him in an hour. He showed us the house. We had the money. I think the rent was $250/month. We got the house. Twenty-first and Southeast Salmon.

The house was built at the turn of the nineteenth century. It had gigantic rooms with drafts jetting through them, strong enough to sing and to slam doors.And yet, the house had an elegance shuffling atop the once graceful lines of its fancy Victorian architecture.

Thea and Frank moved in with us. But within a month, they broke up. Frank moved out. Then. Thea moved out. Donny didn’t find a job. I was down to my last couple hundred dollars. I found a part-time job as a legal secretary the first day I looked. I could type like a fiend. But I wasn’t making enough money for the both of us. And anyway, Donny needed to get a damn job. I was getting really pissed off.

The house was so cold, for instance, by early November, we saw our breath. I kept turning up the thermostat, but nothing happened. Finally, the landlord told us we needed to buy oil to fill the oil tank. The what? I’d never even heard of buying oil to heat a house. I didn’t even know it was a thing people did. I’m from Stockton. And anyway, we didn’t have money to buy oil.

“I THOUGHT YOU WERE GOING TO GET A DAMN JOB!” I kept screaming. “I’M SO PISSED. SO PISSED YOU’RE SPENDING ALL MY FUCKING MONEY AND YOU WON’T GET A FUCKING JOB! YOU HAVEN’T EVEN LOOKED!”

“I know,” Donny said.

YAY. Donny finally got a job a few weeks later as a floor aide at Denville. Denville was the state mental institution forty miles out of town. Swing shift. He would do just about everything, from taking communion from schizophrenic Jesus impersonators, to redirecting resident painters away from feces as their preferred painting medium.

Donny loved it. He could stay calm no matter what. He was like a lake, like floating on a lake. However, his slow current made the floating much more difficult. At least for me.

By Christmas Eve, we still didn’t have heating oil, or the money to buy it. Plus, Donny had to work on Christmas Eve until six Christmas Day. It was not very festive.

I sat on the couch in the middle of our gigantic freezing living room, wrapped in a scratchy blue wool blanket I’d grown up with, eating mustard-glazed chicken breast and blueberry pie. Donny had cooked dinner before he left. It was, frankly, delicious. It tempered my despair.

I watched Jackie Gleason reruns and my breath for nine hours. It was sleeting outside. Sleet was pelting the windows like BB’s. It was pelting my soul. I swear.

I blamed everything on Donny. Because Donny was a boulder that alit on a flat surface. And he was THERE. And I was a gnat, darting for every bulb, every apple, every odor. Because Donny was lava that had already cooled and hardened. And I was the molten upheaval. Because Donny rolled slowly like a turtle. And I shimmied like an ass.

It became obvious there was just no subset created. But. Instead of changing the situation, I grew impatient. And mean.And Donny just stopped. He stopped everything, like wanting to have sex with me. I screamed and wept histrionically. I moaned. I dragged out the disintegration of our relationship as if it were tragic. It wasn’t.

I wrote a bunch of sloppy sad poems about Donny. But truthfully, Donny didn’t break my heart. My heart wasn’t really involved. And either was Donny’s. Donny just broke a plate at the long ostentatious table of my ego. But I didn’t get it at the time.

Months later, I read the Donny poems at an open mike. Virginia Davis, a fine, strange poet, stood up and shouted, Truth! I want the truth! These are lies!

That shut me up for months.

Author’s Note

Brontosaurus Illustrated is a stretched memoir recounting a horrific rape and its after-effects, written and illustrated by the victim/survivor 40+ years later.Leanne Grabel, M.Ed, is a writer, illustrator, performer, and special education and language arts teacher (in semi-retirement). In love with mixing genres and media, Grabel has written and produced numerous spokenword shows, including “The Lighter Side of Chronic Depression,” “Anger: The Musical,” and “The Little Poet.” Her books include Lonesome & Very Quarrelsome Heroes, Short Poems by a Short Poet, Badgirls (a book of flash nonfiction and a theater piece about incarcerated teenage girls in treatment), and most recently, Assisted Living, a chapbook of graphic rectangular prose poems. Grabel has just completed Brontosaurus Illustrated, an illustrated stretched memoir about rape. Grabel’s collection of graphic rectangular prose poems Gold Shoes will be published later this year.